[ad_1]

Apple Watch has introduced a host of health benefits over the past six years, including heart health monitoring / ECG readings, fall detection, blood oxygen, exercise tracking, and has become more widely used in health studies. However, researchers at Harvard and the University of Michigan have now shared their concerns about relying on Apple Watch for studies with the laptop’s algorithms creating “black boxes.”

Reported by The Verge, JP Onnela, associate professor of biostatistics, detailed the potential problems associated with using Apple Watch for research studies. The particular case he looked at involved heart rate variability data collected by Apple Watch, finding it inconsistent, and he believes the cause could impact other studies as well.

The concern depends on how Apple updates its laptop’s algorithms over time, meaning that “data for the same period may change without warning.”

“These algorithms are what we would call black boxes, they are not transparent. So it’s impossible to know what’s in them, ”JP Onnela, associate professor of biostatistics at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and developer of the open source data platform Beiwe, told The Verge.

Devices like Apple Watch are known to export information only after being processed by algorithmic filters, which can be problematic for “repeatable science”. This is why Onnela generally sticks to research devices for studies that produce raw data, but he was keen to learn more about the use of Apple Watch in an upcoming study and the importance of the issues with it. potential data.

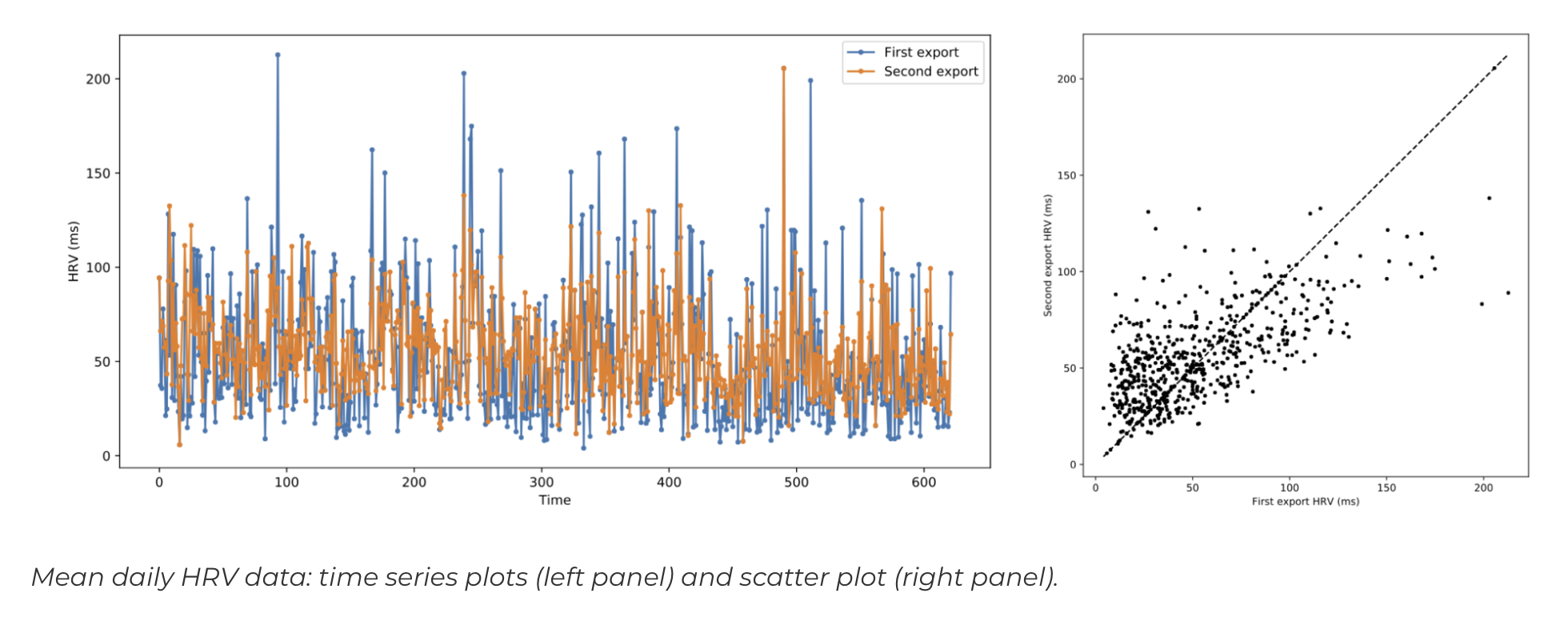

Thus, they verified the heart rate data that his collaborator Hassan Dawood, researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, exported from his Apple Watch. Dawood exported his daily heart rate variability data twice: once on September 5, 2020 and a second time on April 15, 2021. For the experiment, they looked at data collected during the same time period, from early December 2018 to September 2020.

Onnela was ready to see differences in the same exported data at two different times. And their means ended up being similar at 52 vs. 55, however, the variances showed big differences at 1240 vs. 572 and the same data also had a relatively low Pearson linear correlation of 0.67.

Onnela explained more in a blog post:

To be clear, this data covers the same date range, so it must be the same. In fact, their averages are very similar, 52 versus 55 for the first and second export, respectively, but their variances are very different: 1240 versus 572. To better understand this, I made a scatter plot of the values of one time series against the other. The dotted identity line is where we would like to see the dots fall if they were the same, as we hope. Instead, there is a lot of dispersion in the data, and their Pearson linear correlation coefficient is only 0.67. It is not a very high correlation.

Keep in mind that this is just an informal example of Apple Watch data and not a research study, but that was enough to worry Onnela anyway.

Speaking to The Verge, Onnela also used the example of body weight tracking as being affected by shifting algorithm issues. But it all probably depends on the type of use:

For someone who only has an occasional interest in monitoring their health, this can be fine – the differences won’t be major. But in research, consistency matters. “That’s the problem,” he says.

Olivia Walch, a sleep researcher at the University of Michigan, spoke about this, claiming the use of devices that provide raw data:

“It’s validating, because I’m riding my little soapbox on the raw data, and it’s good to have a real-life example where it really matters,” she says.

Another interesting point about data reliability is that different study participants wear smartwatches with different software and algorithms.

Ever-changing algorithms make the use of commercial clothing for sleep research almost prohibitive, Walch explains. Sleep studies are already expensive. “Are you going to be able to attach four FitBits to someone, each running a different version of the software, and then compare them?” Probably not.”

…

Someone could, for example, conduct a study using a wearable device and come to a conclusion about how people’s sleep patterns have changed based on adjustments in their environment. But this conclusion might only be true with this particular version of the laptop software. “Maybe you’d get a completely different result if you just used a different model,” Walch says.

However, Walch said that looking for broader trends on a “macro scale” can still be helpful with wearable devices like Apple Watch:

“If you care about things on this macro scale, then you can make the call as you continue to use the device,” Walch explains. But while the specific heart rate variability calculated each day is important to a study, it may be riskier to rely on the Apple Watch, she says. “It should get people thinking about using certain portable devices if the rug is in danger of being ripped from under their feet.”

Apple did not respond to The Verge for comment on the issue.

FTC: We use automatic affiliate links which generate income. Following.

Check out 9to5Mac on YouTube for more Apple news:

[ad_2]

Source link