[ad_1]

Photo illustration of Lisa Larson-Walker. Pictures of Lisa Larson-Walker, Arroyo Fernandez / NurPhoto via Getty Images.

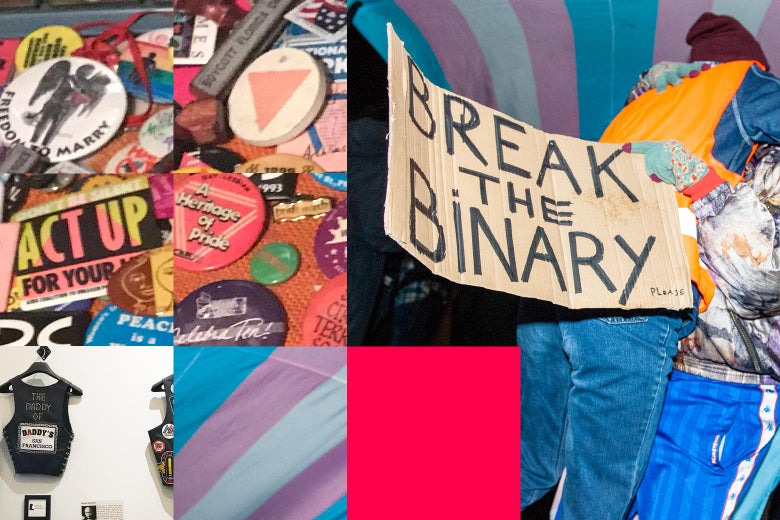

This piece is part of the Legacies issue, a special month series of pride from Outside, At Slate, for its coverage of LGBTQ life, thought and culture. Read an introduction to the number right here.

Recently, one of my middle-aged colleagues spoke to me about an aspect of her identity that I had not seen coming. Despite a long sexually satisfying marriage with a man and an almost complete absence of female lovers in her life, she told me, a gay man, with great enthusiasm, that her discomfort with heteronormative stereotypes had it. inspired to identify now to "queer. "Because I like it and I despise the confrontation a lot, I did not hurry for it. Instead, I smiled and chirped, "Welcome to the club!

Two weeks later, a 22-year-old acquainted me that although she had never enjoyed a kiss from another woman and after dating boys since puberty, she had intense "thoughts" about her wife. friends. She followed this step several months later by reporting that she had fallen in love with a man. Eight months later, they got married. Yet she still wanted to put the word Q on herself, in her case to mean "interrogation".

I doubt that anyone up to a certain age, fluent in the current evolution of LGBTQ identity concepts and terminology finds some of this unusual. They would not have any problem with that either. And intellectually, me neither. But down there, where emotions are struggling against the inevitable ghosts of our past, I have a serious problem. Hearing each of the revelations above, I found myself suppressing feelings of confusion, distance, denigration, irrelevance and, because of all this repression, rage.

I directed all of this towards homosexuals, that is, people in their late 40s to early 60s, all of whom had left in the 1970s and 1980s. Almost every one of them accurately reflected my feelings, before sharing similar stories of colleagues and acquaintances in their own lives.

It seems that many of us at this time are struggling to reconcile our enthusiasm for opening the era of sexual and gender fluidity with the past experienced, when sexual rigidity It's proven to be an indispensable tool, both for us and for the movement. At the time, it was not a question of "questioning", but of affirming, not of exploring, but of declaring. And this story counts a lot.

At the time, it was not a question of "questioning", but of affirming, not of exploring, but of to declare.

Approaching the 50th Pride's birthday, it's important to recognize the debt that today's fluidity owes to yesterday's rigidity, to see how one predicted the other, but to create a precarious relationship today.

In the first decade or so after the Stonewall riots, homosexuals had to send the clearest, most powerful and most fixed message about our sexuality and identity. It was the only effective way to talk about family members, friends and colleagues while he was extremely ignorant, even hostile. The lack of nuance in our announcement has eliminated any room for maneuver so that better-off people can consider our feelings as a fad, a provocation or an illusion. Because we have been told in many ways, clear and implicit, that we do not exist and that it certainly should not, only the most strident and narrow counter-argument would begin to assert our point of contention. view. Moreover, it was the surest way of not closing in the closet, at least in the minds of those who could not conceive that we existed elsewhere.

A similar dynamic applied to the political organization. The focused ideology you need to fuel a young movement is not made for fine distinctions. It's as brutal as an advertising campaign and, with a bit of luck, as effective. The focus was not to encourage people to discover their sexuality for personal fulfillment, but to create a thorny newsletter for public consumption to reinforce the profile and message of the movement. To this end, some attitudes eventually took hold that could – and should – strike any contemporary, or allied, LGBTQ identifier as obnoxious.

I am sad to report that three or four decades ago, many cheerful people (including myself) examined some of the people identified as being bisexual with suspicion or contempt. It was not because we did not think that many were telling the truth about their experience. This is because so many people I have known, identified as gay, used the term "bi" as a sexual warning to avoid the risks of total exit. Or, at the very least, they took the trouble on loan as a small step in that direction. The subsequent view of bisexuals as equivocators was reinforced by the fact that even the most progressive expressions of pop culture of the time felt much more comfortable presenting sexually ambidextrous characters than those strictly gay. This includes representations of The show of rock horror images at Cabaretas well as real events such as Elton John's legendary 1976 interview with Rolling Stone in which he described himself as bisexual – a term he would not think of using today.

At this point, it is essential to note that at the time, there was virtually no major star of pop, cinema or sport openly gay. Not even Liberace! Only members of the cult have tested this taboo. When celebrities that everyone knew to be gay – but did not say in the media – were asked about it, they tended to deliver exactly the kind of statements we're hearing from some LGBTQ people right now. They said, "I do not want to be labeled" or "I am only sexual" or "I am open". Today, these descriptions are a sign of open-mindedness. At that time, they had the impression of being a betrayal, a blanket that was pulling back the movement, which gave the impression that those of us who had gone out felt more isolated and vulnerable at a time when their absence had far more serious consequences.

The growing frustration with this situation, intensely intensified by the AIDS crisis, erupted in the vitriol of the "exit" movement of the early 1990s. While I was opposed to an "exit" at the time – thinking that the message of shame was in bold – from this perspective, I am happy that it happened. This has significantly increased the number of important people publicly disclosed as being homosexual, which has resulted in a high level of acceptance for the rest of us. That among a lot other elements have led to an exponential confidence in the movement, to the point that today he feels free enough to add as many letters, applications and variants as he wishes to his catalog.

As wonderful as it is in many ways, today's openness is not without consequences. If almost all progressive-minded people can find a way to identify themselves as pedantic, what exactly does this term mean? When I hear about fluidity in this context, it sounds like something that has been done to erase the history of homosexuals …my history, drowning it in inclusion to broaden its influence. This may be an inevitable part of advancement. After all, every movement ends up becoming useless if it is sufficiently successful.

Of course, we do not have to worry about such a radical result. Dozens of battles in the fight for LGBTQ rights remain, and setbacks for every advance earned beckon us every turn. But if we want to engage them effectively and honestly, we will need the experiences of the past to inform the movement's new attitudes and actions. This is the only way to bridge the growing gap between LGBTQ generations and to unite. I only hope that the age of fluidity will be sufficiently open to accept it.

Learn more about Outward's Legends problem.

[ad_2]

Source link