[ad_1]

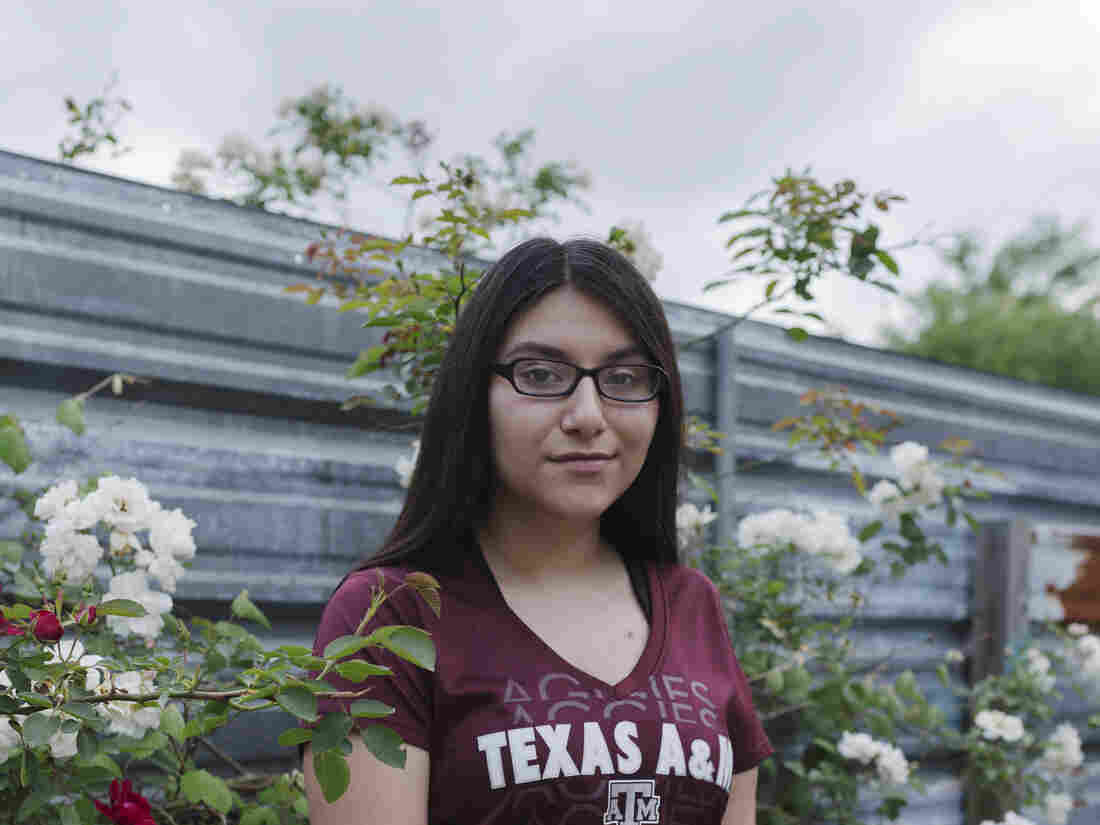

Sarah Salazar was 16 when an armed man entered his class in Santa Fe, Texas, and changed his life forever.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

Sarah Salazar was 16 when an armed man entered his class in Santa Fe, Texas, and changed his life forever.

Allison Hess for NPR

It is 5 am and Sarah Salazar prefers to sleep. Not just because it's early. Or because she is a teenager and can not sleep enough. Doctors say that the shotgun bullets embedded in his shoulder, lungs and back have caused the lead level to soar and let him feel tired most of the time.

Her injuries also make it difficult for Sarah to even do simple tasks, like taking a bath. Her home, in the small town of Santa Fe, Texas, has a shower for six women – Sarah, her mother and four sisters – so she gets up early, before everyone else, to take her time in the shower.

Later, in her room, Sarah chooses a shirt for the day – although it is certainly not her favorite navy blue top with thin white stripes. His wide and open neckline is now too wide, too open, too revealing. Sarah's younger sister, Sonya, helps her to fix her bra.

Around 6:20 am, Sarah goes to school with her best friend, Emma Lovejoy, and Emma's grandmother in their Jeep Wrangler. Unlike her sisters, Sarah, now a junior, no longer takes the bus to go to Santa Fe High School. Not since she missed the bus on May 18, 2018 – the day that changed her life forever.

According to the police, this is the day a 17-year-old student wore a A Remington 870 shotgun and a 38 caliber pistol in Sarah's art class. He killed eight students and two teachers and injured 13 others, including Sarah.

Here is her story – the story of a teenager's long and slow struggle, physically and emotionally, to rebuild her life after a school shooter almost took her.

May 18, 2018

Satellite imagery of Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, Texas, about 35 km southeast of Houston.

ScapeWare3d / DigitalGlobe / Getty Images

hide legend

activate the legend

ScapeWare3d / DigitalGlobe / Getty Images

Satellite imagery of Santa Fe High School in Santa Fe, Texas, about 35 km southeast of Houston.

ScapeWare3d / DigitalGlobe / Getty Images

At the start of the shootout, Sarah, then 16, is the last person to hide in the shopping closet of her art room. His classmates try to block the door, but the shooter can still see them through a small window in the door. He points his rifle at the glass and shoots.

Small pellets of lead explode in the closet. Sarah's neck, left shoulder and leg are affected. She drops to the floor and, trying to stay calm, looks for a classmate.

Trenton Beazley is also touched, in the back. The second year catcher of the baseball team feels a tug and turns around. In the dim light, he can see a girl bleeding profusely from the neck and shoulders, her long black hair on her face. Sarah gasps for help.

Trenton catches Sarah's jacket on her lap and wraps it around her shoulder like a tourniquet to stop the bleeding. He does not remember thinking about it.

"It's not like you're practicing something like that, it's more like an instinct, you look down and see something that might work," Trenton said later.

Before she is shot, Sarah prays God to protect everyone in the closet.

After being touched, she calls God again:

I am here. If you're ready to take me home, I'm not scared. But if you want to let me stay, then that's fine too.

Students wait more than half an hour for the shooting to stop and help arrives.

Emergency teams gather in the Santa Fe High School car park after the shooting.

Daniel Kramer / AFP / Getty Images

hide legend

activate the legend

Daniel Kramer / AFP / Getty Images

Emergency teams gather in the Santa Fe High School car park after the shooting.

Daniel Kramer / AFP / Getty Images

Sarah's mother, Sonia Lopez, recites her own prayers as soon as she learns that there was shooting in her daughters' school. She tries to get to Santa Fe High but, at a designated meeting point, has to wait for Sarah to come back to see her.

Bus after bus, the students are reunited with their families. Sarah never comes.

"Lord, please, be with Sarah, let her go," Lopez prays again and again.

Dr. Brandon Low was on call when Sarah was rushed to the hospital. Experienced in dealing with bullet trauma, Low states that Sarah's injuries were so devastating because she had been hit at close range with a powerful weapon in a vulnerable part of her body.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

Dr. Brandon Low was on call when Sarah was rushed to the hospital. Experienced in dealing with bullet trauma, Low states that Sarah's injuries were so devastating because she had been hit at close range with a powerful weapon in a vulnerable part of her body.

Allison Hess for NPR

The news comes in: Sarah was shot and taken to HCA Houston Healthcare Clear Lake. The explosion caused severe bleeding in Sarah's neck. The doctors decided that it was too risky to repair the two damaged veins. So they tied the ends. His shoulder was broken and remains of the shell are scattered throughout his body.

For Lopez, all this seems to be a blessing.

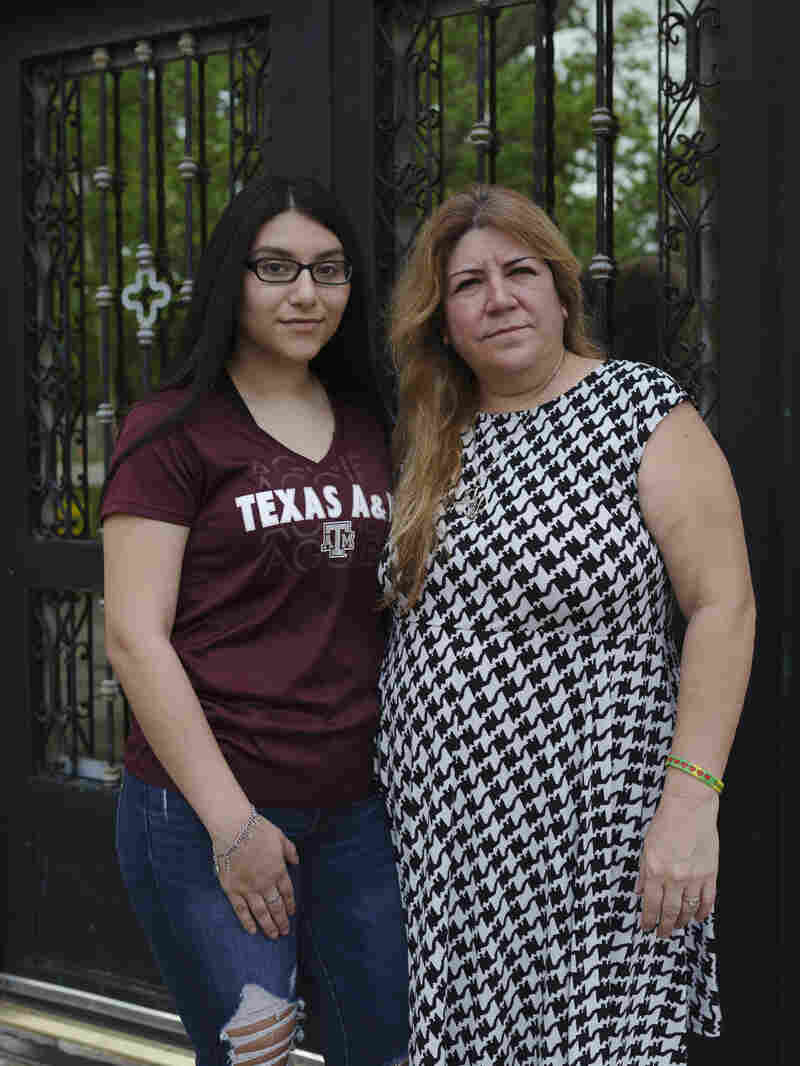

"I know that the Lord was there with [Sarah] because she called to him, and he answered. She may not have seen it, but I know that it has protected her because none of her vital organs have been touched. His brain was intact, "says Lopez.

Nevertheless, it takes consecutive emergency surgeries to stabilize Sarah. Dr. Brandon Low, orthopedic surgeon on duty, examines the scanners and knows this is a devastating injury.

"The articulation between the shoulder and the cavity was destroyed – it was barely visible, even at X-rays." Low explains.

Low often treats patients with gunshots and says that Sarah's injury is a triple shot: point-blank shooting with a powerful weapon in a vulnerable part of her body.

An X-ray taken before the emergency surgery at Sarah's shoulder. "The joint between the shoulder and the cavity was destroyed – it was in pieces, barely visible even on X-rays," says Low, the orthopedic surgeon on call on the day of the shooting.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

An X-ray taken before the emergency surgery at Sarah's shoulder. "The joint between the shoulder and the cavity was destroyed – it was in pieces, barely visible even on X-rays," says Low, the orthopedic surgeon on call on the day of the shooting.

Allison Hess for NPR

The surgeon joins the rest of the trauma team in the operating room and begins removing non-viable tissues from the body to prevent infection. They also remove as much pellets as possible, as well as fragments of the shell itself, before sewing the wound.

Nearly a month later, Sarah will have a full replacement of the shoulder.

SUMMER

Jai Gillard, who was in the class where the shooting started, watches a cross for Sabika Sheikh, a student in Pakistani exchange, before signing it in memory of the victims of the shooting at Santa Fe High School in Texas.

Brendan Smialowski / AFP / Getty Images

hide legend

activate the legend

Brendan Smialowski / AFP / Getty Images

Jai Gillard, who was in the class where the shooting started, watches a cross for Sabika Sheikh, a student in Pakistani exchange, before signing it in memory of the victims of the shooting at Santa Fe High School in Texas.

Brendan Smialowski / AFP / Getty Images

Sarah's hospital room fills with balloons, flowers and visitors. Pop star Justin Timberlake promises tickets for his upcoming show in Houston. NFL star J. J. Watt visits. "Santa Fe Strong" begins to appear on T-shirts and billboards throughout South Texas.

The doctors must close Sarah's mouth so that her broken jawbone can heal, limiting her diet to chicken broth and applesauce. Her best friend, Emma, visits her almost every day. They play cards and watch Netflix. At first, Emma is surprised how much Sarah's neck has become swollen – "like a marshmallow," she says.

Seventeen days after the shooting, Sarah is released and returns to her mother's three-bedroom house. Although her jaw is still closed, she begins to supplement her diet by drinking Flamin's Hot Cheetos, her favorite snack. A little taste of his old life.

In July, she begins an aquatic physical therapy to exercise her new shoulder joint prosthesis and regain strength. Sarah feels more comfortable in the water. His arm is lighter and the pain is too.

In August, the first day of school, Sarah does not hesitate to return to class in Santa Fe High. She wants to focus on her first year and prepare for the university. His dream school is Texas A & M University at College Station. His dream career: nurse anesthetist.

Sarah and her mother, Sonia Lopez, say that her strong faith has been a source of strength over the past year.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

Sarah and her mother, Sonia Lopez, say that her strong faith has been a source of strength over the past year.

Allison Hess for NPR

Sarah's mother, Sonia Lopez, is more worried about her daughter's return. First, how will she navigate the busy halls of a school with 1,400 students?

"We were afraid people would see her in the hallways, you know, and she said, 'No, I can do it, I can do it, I do not need anyone who carries my books , "" Lopez says.

Sarah later acknowledges that the return is sometimes difficult. Whenever someone knocks on the door of the class, she must check before she can continue her work. The new alarms on the doors are noisy and make her anxious.

In September, Sarah's mother and other families who were irreparably scarred by the massacre appear before the Santa Fe School Board. They publicly acknowledge their loved ones who were killed and ring a bell for everyone. them. They then acknowledge the 13 wounded, including Sarah, although the council chairman is trying to end the group.

Lopez is concerned that the council is not doing enough to help the community recover and protect itself from future threats. At the lectern she begs the district.

"We must give the example, so that what happened to my daughter will not happen again," she said, on the verge of tears.

In the crowded audience, Sarah is sitting silently, her left arm in a sling.

FALL

"Santa Fe Strong" began appearing in Santa Fe and South Texas soon after the shooting at school.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

"Santa Fe Strong" began appearing in Santa Fe and South Texas soon after the shooting at school.

Allison Hess for NPR

On a sunny Saturday night, a DJ infuses Mexican ranchera and cumbia music between Bruno Mars and Miley Cyrus as dozens of people mingle in Santa Fe's community center at Runge Park.

This is not Sarah's party. This is his younger sister Sonya quinceañera, his 15-year celebration – a rite of passage in many Hispanic families. It's also the first time that their expanded circle of family and friends has something to celebrate since filming.

Sarah arrives late after picking up the last of the balloons. She is wearing a short sleeveless pink dress and a black crepe jacket to cover the scar on her shoulder. His father, Nick Salazar, proudly accompanies him to greet family members and friends.

A photo of Sarah with her four sisters is hanging in their home in Santa Fe, Texas. Sarah's sisters are a constant source of love, laughter and support since filming.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

A photo of Sarah with her four sisters is hanging in their home in Santa Fe, Texas. Sarah's sisters are a constant source of love, laughter and support since filming.

Allison Hess for NPR

"It looks like she's having fun," he says later. "It's good to see her smile and all, I'm happy she's happy."

"Some of those people I met during the shooting," says Lopez while she serves rice, beans and cabrito with lamb to a long line of diners.

Another survivor, Flo Rice, spends with her husband. The former substitute teacher walks with a cane and smiles for a selfie with Sarah.

After the official dance and presentations, Sarah slips out and removes her black heels with ankle bridle. She is tired and thinking about going home early.

"It was a good distraction. It's nice, "she says. "It was good not to think of anything else."

The fact is that many things are still difficult for Sarah. She can not raise her left hand beyond her waist. At her father's house, she can not reach the microwave to heat ramen noodles. In addition, her mother does not think her shoulder is healed enough that she can drive safely. Even after November 17, Sarah still depends on others to get around.

Some days, she would like to simply put her long black hair in a ponytail without help.

As winter approaches, Sarah's entourage – her mother, her four sisters, and Emma – help create a new routine. When the insurance company hits him hard, refusing to pay for other water therapy sessions, his older sister, Suzannah, encourages Sarah to do exercises at home. His mother keeps track of his medical appointments. Every morning, sister Sonya, who shares a room with Sarah, helps her get dressed, while her two younger sisters, Star and Sophya, take part in Sarah's household chores and help feed the animals. domestic family.

Between all this work, there is still plenty of time to have fun. The family organizes a regular game night on Friday. And each night, Sarah finds solace and distraction with the many animals in the family: four dogs, two cats, four parakeets, 11 fish, as well as a turtle and a goat named Michelle. The goat was supposed to be dinner at the quinceañera but now hangs out in the yard with a menagerie of chickens and ducks.

Sarah loves to curl up in bed with her gray kitten or practice spanish while gorging on her favorite telenovela, Sin senos sí hay paraíso.

"Netflix is the cure," she says with a smile.

"I have the impression that she is slowly reaching a new normal, a new joy and other things." But I would not say that she is still completely there, "says Emma. "It depends on the day, but ultimately I have the impression that she is still dealing with it and she's going to do it for a while."

WINTER

Once every two weeks, Sarah skips a counseling period at school to join a small therapy group with a few other people affected by the shooting, although they do not talk much. Only twice have they really discussed this day.

Instead, they do arts and crafts. A Christmas wreath hanging now at the door of the family's laundry room. A rock covered with magazine clippings that sits on the sill of Sarah's window. Sarah prefers to create things that speak. The art makes him feel calm.

"I do not know how talking about how I feel about it will help me," she says.

But she knows she has a long way to go emotionally.

Recalls of the shooting, large and small, remain in Santa Fe a year later.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

Recalls of the shooting, large and small, remain in Santa Fe a year later.

Allison Hess for NPR

"The wellness counselor at school – I have a lady I talk to – she says I'm keeping my emotions and that's not good," Sarah says. "I do it, and so, emotionally, I did not go that far because I'm trying to keep it to myself."

Even before the trauma, Sarah was rather quiet. But since May, even her best friend has struggled to know what happens sometimes. And they know each other since the first year.

"She does what I do whenever something bothers me – puts me in this kind of foreground that makes everyone think that everything is going well," says Emma. "But you know that there are still things that bother her."

At school, casual remarks can trigger difficult emotions. Sarah can not bear to hear students mention their weekend hunting projects – a common topic in this small Texas town. Even the moment of silence that his school retains every morning can be difficult.

"Sometimes they say to themselves:" OK, pause for a moment of silence ". and I begin to pray. And then, they tell me: "OK!" And I say to myself, "I can not even take a break," said Sarah, for her, prayer has been a constant comfort "morning and evening and whenever I need someone" .

Sometimes Sarah wonders what will happen to the former student accused of shooting at her and killing so many of her classmates and teachers. One day in February, she and her mother go to the Galveston County Courthouse. They sit near the front to be able to look at it. When the accused mixes inside, handcuffed, his lawyers ask the judge to change his place. They argue that mass shooting has so attracted the attention of the community that it will not benefit from a fair trial.

Sarah watches him closely. This May day, in the arts room, she never looked at the shooter in the eye. That day, she wants to look him in the eyes.

But he keeps his head down.

SPRING

Sarah's sister, Sonya Salazar, stands with their mother before Sarah's operation at UTMB Health in League City, Texas.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

Sarah's sister, Sonya Salazar, stands with their mother before Sarah's operation at UTMB Health in League City, Texas.

Allison Hess for NPR

As the filming anniversary of the month of May approaches, the emotions that Sarah keeps buried inside intensify, especially sadness.

"Some days I wake up and say to myself," The day will not be good, "she says." It's like: "No, I just want to go back to bed." Or just, like, all day long, I guess I'm having a good day and I'll just become sad. "

Sarah does not know how she will feel at the birthday. Or what she's going to do.

"It's been just a year, but it's not what I feel because the past year is so fast that I do not have time to deal with it," she says.

Sarah's physical recovery has also been slow. She has undergone six surgeries since the shooting and, almost 11 months later, she now needs a seventh. Pellets from the blast remain embedded in his chest, shoulders and back, and have pushed his lead level four times beyond the acceptable limit.

"It gives her headaches, stomach ache, dizziness," says her mother, Sonia Lopez. "I can not wait until they're gone – all those pellets."

It's still five o'clock in the morning, mid-April, and Sarah is already awake. Do not claim the shower though. She, her mother and younger sister Sonya settle into their rusty Toyota Corolla at the outpatient surgery center of UTMB Health in League City.

Inside, Sarah is calmly waiting in the preoperative area.

Dr. Ikenna Okereke, her mother Sonia Lopez, Sarah, anesthesiologist Sandhya Vinta and a nurse are making the final preparations before Sarah's operation.

Allison Hess for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Allison Hess for NPR

Dr. Ikenna Okereke, her mother Sonia Lopez, Sarah, anesthesiologist Sandhya Vinta and a nurse are making the final preparations before Sarah's operation.

Allison Hess for NPR

"I saw The anatomy of Gray, "she says." There is this episode where a girl is afraid to be operated on. I do not know, I'm not scared. "Because everything is so routine now.

Sarah has an unusual request for the surgeon. She wants to keep the pellets that he finds.

"They were inside me, so they are mine," she says.

"I will have to talk to some people, I do not know in terms of evidence, chain of command, forensics," says Dr. Ikenna Okereke.

The fog of anesthesia sits on Sarah. Lopez bends over and kisses his forehead.

"God bless you," she murmurs.

While Sarah is operated on, her mother calls the staff, "May everyone be blessed if you work on Sarah today, know that many people are praying for you today!"

The doors of the operating room are closed.

Once again, Lopez is waiting for his daughter, Sarah Grace, to come back to him.

[ad_2]

Source link