[ad_1]

Nicolas Taberlett / Nicolas Pléhoun

Visit the small sea of Lake Baikal in Russia during winter, and you will likely see an unusual phenomenon: a flat rock balanced on a thin base of ice, resembling a pile of Zen stones common in Japanese gardens. This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as Baikal Zen training. The typical explanation for how these formations occur is that rocks pick up light (and heat) from the sun, which melts the ice below until only a fine base remains for support her. The water under the rock regenerates at night, and it has been suggested that the wind can also be a factor.

Now, two French physicists believe they have solved the mystery of how these structures formed, according to a new article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences – and their solution has nothing to do with the thermal conductivity of stone. Instead, they attribute the formation to a phenomenon known as sublimation, where snow or ice evaporates directly into vapor without going through an aqueous phase. Concretely, the shadow cast by the stone hinders the sublimation rates of the surrounding ice in its vicinity, while the more distant ice sublimates at a faster rate.

Many similar formations occur naturally in nature, such as capes (the long, threadlike structures formed over millions of years in sedimentary rocks), fungi, or bedrock (the base has been eroded by strong winds and dusty) and the glacial tables (a large unstable rock on a tight pad of ice). But the basic mechanisms by which it is formed can be completely different.

For example, as we reported last year, a team of applied mathematicians from New York University studied the “stone forests” common in parts of China and Madagascar. These sharp rock formations, such as the famous Stone Forest in Yunnan Province of China, result from the dissolution of solids into liquids in the presence of gravity, resulting in natural convection flows.

On the surface, these stone forests look like “penitents”: plumes of snow-capped ice forming in extremely dry air can be found high up in the glaciers of the Andes. The penitents were described by Charles Darwin in 1839 during an expedition in March 1835 in which he made his way through snow fields covered with penitents on his way from Santiago, Chile, to the city Argentina from Mendoza. Synthetic reproduction of repentants in vitro. But penitents and stone forests are actually quite different in terms of the mechanisms involved in their formation. The tips of the stone forests are sculpted by flows which do not play a large role in the training of penitents.

Some physicists have suggested that penitents are formed when sunlight vaporizes snow directly into vapor (sublimation). Small ridges and troughs form and sunlight is trapped in them, creating additional heat that etches even deeper troughs, and these curved surfaces in turn act like a lens, further speeding up the sublimation process. An alternative proposal adds an additional mechanism to account for the particular cyclic spacing of repentants: a combination of vapor diffusion and heat transfer results in a very steep temperature gradient and, therefore, a higher rate of sublimation.

Nicolas Taberlett / Nicolas Pléhoun

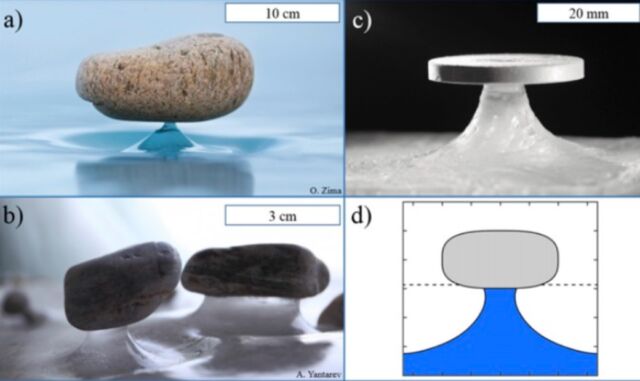

In the case of Baikal Zen rock formations, the process appears similar to the penitent sublimation hypothesis, according to co-authors Nicolas Taberlet and Nicolas Plehon of CNRS in Lyon, France. Earlier this month, they published a somewhat related study in Physical Review Letters on the natural formation of glaciers (a rock supported by a thin column of ice). They were able to produce small-scale artificial ice tables in a controlled environment and discovered two competing effects that controlled the onset of ice table formation.

With smaller stone caps with higher thermal conductivity, the geometric amplification of the heat flow causes the cap to sink into ice. For a larger lid with lower thermal conductivity, the reduced heat flow comes from the fact that the lid has a higher temperature than the ice around it, forming a table.

In this latest study, Taberlet and Plihon wanted to explore the mechanisms underlying the natural formation of Baikal Zen structures. “The rarity of this phenomenon stems from the scarcity of thick, flat, snowless ice caps, which require long-lasting cold and dry conditions,” the authors wrote. “Weather records show thaw is almost impossible, and instead atmospheric conditions (wind, temperature, relative humidity) favor sublimation, long known to be characteristic of the Lake Baikal region.”

The researchers therefore attempted to reproduce the phenomenon in the laboratory to test their hypothesis. They used metal disks as experimental stone analogues and placed the disks on the surface of blocks of ice in a commercial freeze dryer. The tool freezes the material, then reduces the pressure and adds heat, so the frozen water heats up. The higher reflectivity of metal discs compared to stone prevented the discs from overheating in the freezing and drying chambers.

Outside the earth

Both aluminum and copper discs produced Baikal Zen configurations, although copper has almost twice the thermal conductivity of aluminum. The authors concluded that the thermal properties of stone were not a critical factor in this process. “Away from the stone, the rate of sublimation is subjected to diffuse sunlight, while the shadow it creates nearby hinders the sublimation process,” the authors wrote. “We show that the stone acts only as a canopy, the shadow of which interferes with sublimation, thus protecting the ice below, creating the base.”

This was then confirmed by numerical modeling simulations. Taberlet and Plihon also found that the cavity or depression surrounding the base is caused by far infrared radiation emitted by the stone (or disc) itself, which improves the overall rate of near-sublimation.

This is quite different from the process that leads to ice streams, despite the similar shape of the two formations. In the case of icy streams, the canopy effect is only a minor factor in the underlying mechanism. “Ice streams appear on lower elevation glaciers when weather conditions melt rather than allow ice,” the authors wrote. “They form in hot air while ice stays at 0 degrees Celsius, and Zen stones form in air cooler than ice.”

Understanding how these formations occur naturally can help us learn more about other things in the universe, where the sublimation of ice produced penitents on Pluto and influenced the formation of landscapes on Mars, Pluto, Ceres, the moons of Jupiter and the moons of Saturn. And many comets. The researchers concluded that “indeed, NASA’s Europa Lander project aims to search for biosignatures on the ice-covered moon of Jupiter, whose surface differential sublimation could threaten the stability of the probe, and this must be fully understood. . “

DOI: PNAS ، 2021. 10.1073 / pnas.2109107118 (حول DOI).

Source link