[ad_1]

Injection of CRISPR solution into crustacean embryos (Parhyale hawaiiensis). Credit: Heather Bruce

It sounds like a “fair story” – “How the insect got its wings” – but it really is a mystery that has puzzled biologists for over a century. Intriguing and competing theories of insect wing evolution have emerged in recent years, but none have been entirely satisfactory. Finally, a team from the Laboratory of Marine Biology (MBL), Woods Hole, settled the controversy, using clues from long-standing scientific papers as well as cutting-edge genomic approaches. The study, conducted by MBL research associate Heather Bruce and MBL director Nipam Patel, is published this week in Nature’s ecology and evolution.

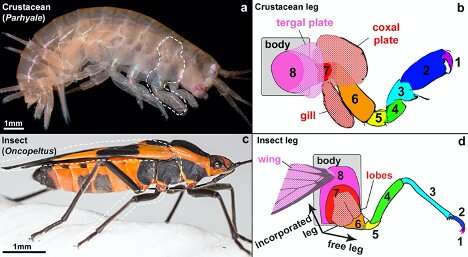

Insect wings, the team confirmed, evolved from a growth or “lobe” on the legs of an ancestral crustacean (yes, crustacean). After this marine animal’s transition to land around 300 million years ago, the leg segments closest to its body became incorporated into the body wall during embryonic development, possibly to better support its weight on earth. “The lobes of the legs then moved to the back of the insect, and those then formed the wings,” says Bruce.

One of the reasons it took a century to figure this out, Bruce says, is that it wasn’t understood until 2010 that insects are most closely related to crustaceans in the arthropod phylum, as revealed genetic similarities.

“Before that, based on morphology, everyone had classified insects in the myriapod group, as well as centipedes and centipedes,” Bruce explains. “And if you look in the myriapods where the insect wings come from, you won’t find anything,” she says. “Insect wings were therefore considered to be ‘new’ structures that arose in insects and did not have a corresponding structure in the ancestor – because the researchers were looking in the wrong place for the ancestor of the insect. .

“People are very excited that something like insect wings may have been an innovative evolutionary innovation,” Patel says. “But one of the stories that emerges from genomic comparisons is that nothing is new; everything is coming from somewhere. And you can, in fact, know where from.”

Bruce picked up the scent of his now-reported discovery while comparing the genetic instructions for the segmented legs of a crustacean, the tiny beach-hopper Parhyal, and the segmented legs of insects, including the fruit fly Drosophila and the scarab Tribolium. Using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, she systematically turned off five shared genes Parhyal and in insects, and found that these genes corresponded to the six leg segments that are furthest from the body wall. Parhyal, however, has an additional seventh leg segment next to his body wall. Where has this segment gone, she wondered? “And so I started to dig into the literature, and I found this really old idea that had been proposed in 1893, that insects had incorporated their proximal [closest to body] leg area in the body wall, ”she said.

The insects incorporated two segments of ancestral crustacean legs (labeled 7 in red and 8 in pink) in the body wall. The lobe on leg segment 8 then formed the wing in insects, while this corresponding structure in crustaceans forms the tergal plate. Credit: Heather Bruce

“But I still didn’t have the wing part of the story,” she says. “So I kept reading and reading, and I came across this theory from the 80s that not only did insects incorporate their proximal leg region into the body wall, but the small lobes of the leg then grew. moved to the back and formed the wings. , wow, my genomic and embryonic data supports these old theories. “

It would have been impossible to solve this long-standing conundrum without the tools now available to probe the genomes of a myriad of organisms, including Parhyal, which the Patel laboratory has developed as the most genetically treatable research organism among crustaceans.

Research for crustacean wings sheds light on the origins of insect wings

Nature’s ecology and evolution (2020). DOI: 10.1038 / s41559-020-01349-0

Provided by the Marine Biology Laboratory

Quote: How the insect took its wings: Scientists (finally!) Tell the Story (December 1, 2020) retrieved December 2, 2020 from https://phys.org/news/2020-12-insect-wings-scientists -tale. html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for study or private research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link