[ad_1]

Press release

Wednesday, February 20, 2019

NIH-funded study finds children with both conditions have abnormal skin close to eczema lesions

Atopic dermatitis, a common inflammatory skin condition also known as allergic eczema, affects nearly 20% of children, 30% of whom also suffer from food allergies. Scientists have now discovered that children with atopic dermatitis and food allergy had structural and molecular differences in the upper layers of a healthy-looking skin near eczema lesions, unlike children with atopic dermatitis. Defining these differences can help identify children at high risk of developing food allergies, according to research published online today in Translational medicine science. The research was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), which is part of the National Institutes of Health.

"Children and families affected by food allergies must constantly guard against accidental exposure to foods that can cause life-threatening allergic reactions," said Anthony S. Fauci, director of NIAID, "Eczema is a risk factor for the development of food allergies An intervention to protect the skin can be one way to prevent food allergies. "

Children with atopic dermatitis develop patches of dry, itchy, scaly skin caused by allergic inflammation. Symptoms of atopic dermatitis range from minor itching to extreme discomfort that can disrupt the child's sleep and lead to recurrent infections on scuffed and scratched skin.

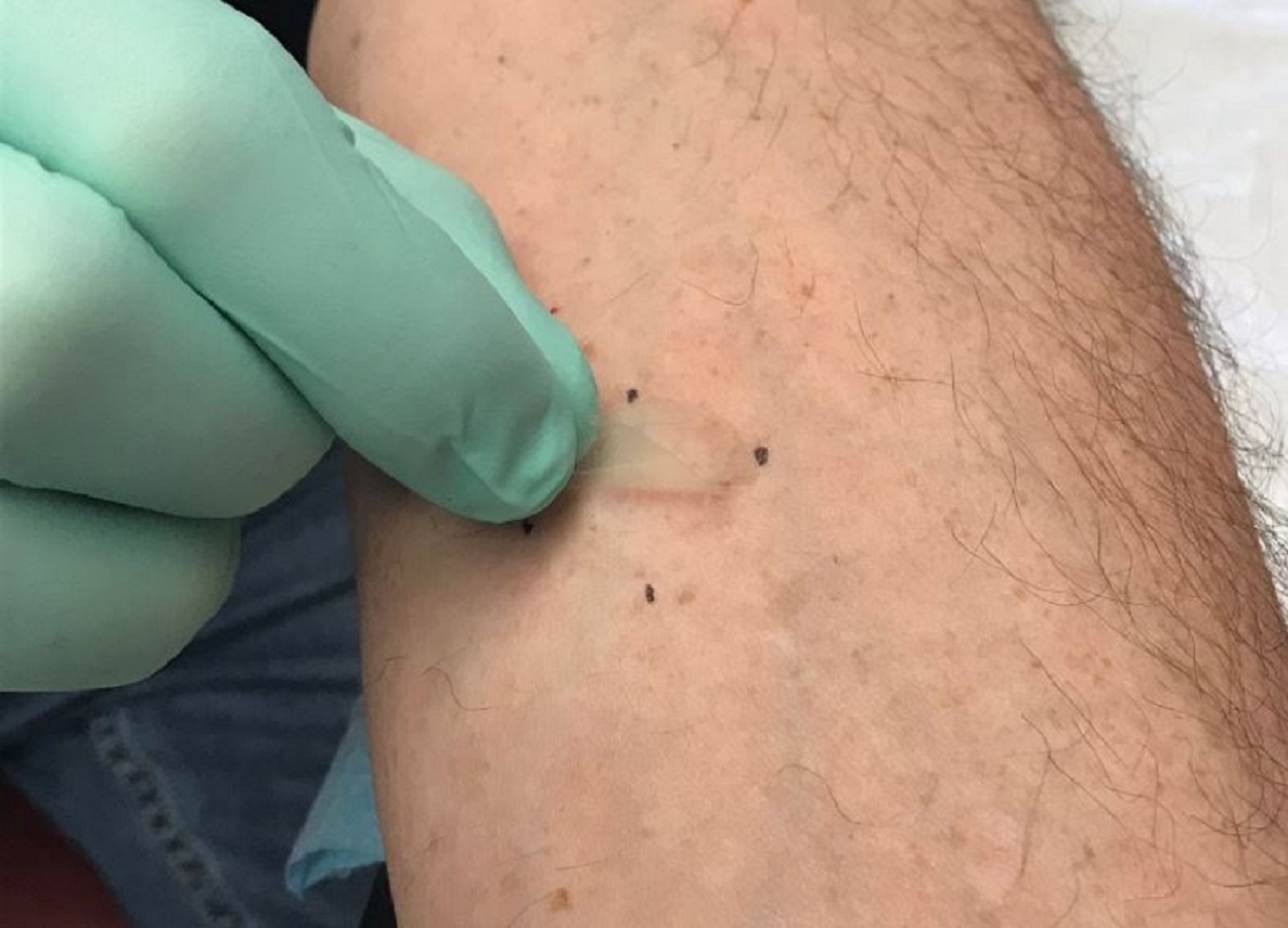

The study, led by Donald YM Leung, MD, Ph.D., of the National Jewish Health in Denver, examined the superficial layers of the skin, called stratum corneum, in areas with severe lesions. eczema and in adjacent areas of normal appearance. The study included 62 children aged 4 to 17 years who had either atopic dermatitis and peanut allergy, atopic dermatitis and no signs of food allergy or any of these two diseases. Investigators collected skin samples by applying and removing small strips of sterile tape on the same area of skin. At each withdrawal, a microscopic underlayer of the first layer of cutaneous tissue was collected and stored for analysis. This technique allowed researchers to determine the composition of the skin in cells, proteins and fats, as well as its microbial communities, the expression of genes in skin cells and the loss of water through the skin barrier.

The researchers found that rashes in children with both atopic dermatitis and food allergy could not be distinguished from rashes in children with atopic dermatitis alone. However, they found significant differences in the structure and molecular composition of the top layer of a healthy, non-lesion-like skin between children with atopic dermatitis and food allergy by compared to children with atopic dermatitis alone. The non-lesional skin of children with atopic dermatitis and food allergy was more prone to water loss and contained an abundance of bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, and had the typical gene expression of an immature skin barrier. These abnormalities have also been observed in skin with active lesions of atopic dermatitis, suggesting that skin abnormalities go beyond visible lesions in children with atopic dermatitis and food allergy, but not in those with atopic dermatitis. with atopic dermatitis alone.

"Our team sought to understand how healthy looking skin could be different in children who developed both atopic dermatitis and food allergy compared to children with atopic dermatitis alone," said Dr. Leung. "Interestingly, we found these differences not in the rash, but in skin samples apparently unaffected a few inches away. This information could help us not only to better understand atopic dermatitis, but also to identify children at greatest risk of developing food allergies before they develop an apparent rash and, ultimately, to tweak their strategies. prevention to reduce the number of children affected. "

Allergists consider that atopic dermatitis is a first step in the "atopic walking", a common clinical progression observed in some children, atopic dermatitis progressing in food allergies and, sometimes, respiratory allergies and allergic asthma. Many immunologists hypothesize that food allergens could reach immune cells more easily through a dysfunctional skin barrier affected by atopic dermatitis, thereby triggering the biological processes that lead to food allergies.

NIAID conducts and supports research – at NIH, in the United States, and around the world – to investigate the causes of infectious and immune-mediated diseases and to develop better ways to prevent, diagnose and treat these diseases. diseases. News releases, fact sheets and other documents related to NIAID are available on the NIAID website.

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH):

The NIH, the country's medical research agency, has 27 institutes and centers and is part of the US Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the lead federal agency that conducts and supports basic, clinical and translational medical research. She studies causes, treatments and cures for common and rare diseases. For more information on NIH and its programs, visit www.nih.gov.

NIH … transforming discovery into health®

Reference

D Leung, et al. The non-lesion skin surface distinguishes atopic dermatitis with food allergy as the sole endotype. Translational medicine science DOI: 10.1126 / scitranslmed.aav2685 2019.

[ad_2]

Source link