[ad_1]

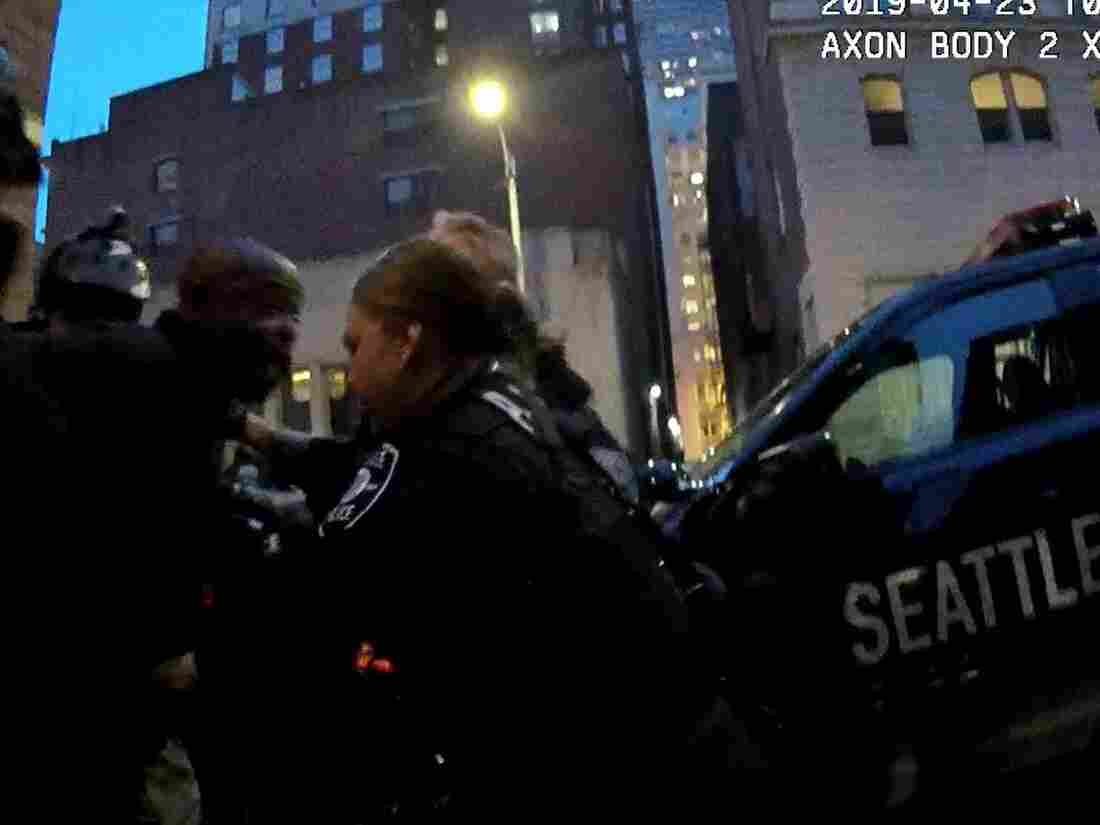

During this incident in April, filmed by the body of a police officer, it took nearly two hours of negotiations and at least a dozen police officers to safely control a man with mental illness who was Was seized from a lane.

Courtesy of the City of Seattle

hide legend

activate the legend

Courtesy of the City of Seattle

During this incident in April, filmed by the body of a police officer, it took nearly two hours of negotiations and at least a dozen police officers to safely control a man with mental illness who was Was seized from a lane.

Courtesy of the City of Seattle

Seattle is facing a crisis of what is sometimes called "visible homelessness" – people who live on the street and struggle with mental illness or addiction. It's a population that often commits small crimes, such as disorderly behavior or theft on display to pay for drugs. And the frustration of the public grows.

Some blame a local reform-oriented criminal justice system for becoming too tolerant.

These critics cite a man with a mental illness who was arrested in March for attempting to throw a woman on a bridge. It turned out that he had already been arrested three times in the past three months for attacking strangers at random and throwing a computer terminal at the library.

He has not been subject to serious criminal penalties for these previous incidents, in part because of his mental health condition.

In April, cameras on the bodies of Seattle police officers captured a man who had claimed a downtown alley and was hunting people with a drain pipe. It took nearly two hours of negotiations with more than a dozen police officers to control it safely.

The public's frustration with the "visible homeless" found its voice in a special show titled "Seattle is Dying", launched an hour ago, by ABC's affiliate, KOMO-TV. It focuses on the debris of tent camps near the downtown core and the behaviors of people with mental illness and drug use.

The video refers to "lost souls roaming the streets, unattached, to their families, to reality" and to people in the city who feel compassion, "but no longer feel safe" .

The video was criticized for its melodramatic character and exaggerating the problem, but it struck a nerve and became an integral part of the city's political debate. Candidates for a local position are now routinely asked if they think Seattle is "dying".

Even a judge weighed. At a forum sponsored by the Downtown Seattle Association, Judge Ed McKenna, president of the Municipal Court, blamed prosecutors for not having fired for crimes committed by drug addicts and sufferers of mental illness.

"We are constantly seeing attacks on police officers. They are charged with offenses, which should probably be judged as crimes. Attacks from bus drivers, health professionals, all of which should otherwise be crimes and accusations. I can not say why this decision is made, "said McKenna.

He said that it was "frustrating" when prosecutors were holding back, because it meant that the criminal justice system had less influence on these repeat offenders.

"For example, an attorney might say," If your client wants to do inpatient treatment, we will refer them to a safe treatment facility. If he does not want treatment, we will ask him for a lot more jail time, "said McKenna." What choice would your client like? "

But this type of pursuit is out of fashion in Seattle. The county attorney no longer charges people for possession of small amounts of drugs – even heroin and methamphetamine – and city prosecutor Pete Holmes does not believe in the "old way" of do things.

In April, Holmes joined the public defenders in an open letter criticizing Judge McKenna for overstepping his role, as he saw it, and attempting to make prosecutors take more severe action. against offenders.

"Prosecutors have been uniformly criticized for laying charges, demanding maximum penalties under the law, knowing that they are inappropriate or simply not in the interest of public security," he said. declared at the time.

In an interview at the time, Holmes said: "What we are talking about, in reality, is to say," Put them in jail. And at least that offender will be out of sight for a certain period of time. "Do not receive treatment, but at least out of public view."

But Holmes added that he also thought the public's "dismay" about the situation on the streets of Seattle indicated a deeper problem.

"We find out that the system is really at its peak, and I think the judge and I agree on that – that these services are really at their limit," Holmes said.

The courts have the bar very high to engage someone in involuntary mental health treatments, and it is difficult to get a lower level outpatient treatment. Thus, even though prosecutors were putting more pressure on these defendants, Holmes asked "for what purpose?"

The city's Municipal Mental Health Court is one such example. The product of a previous wave of criminal justice reforms, it offers defendants with mental illness an alternative to traditional courts. He drops charges for those who accept close supervision and two-year treatment. But lately, the defendants have been less encouraged to follow this path, as the court has lost the opportunity to offer them housing as part of the transaction. Funding for the court housing program has been redirected to the city's largest effort to combat homelessness.

Holmes said that the public is seeing for itself the results of a problem that has not been solved in a long time: what to do with people with mental illness?

"Decades ago, the decision to deinstitutionalize mental health treatment was made," he said, and the alternative promised to community-based mental health treatment centers "n & # 39 "was not built".

As prisons and jails are less likely to house such people, Holmes said he hoped the public would begin to see – and recognize – the unresolved problem of lack of treatment for mental health.

[ad_2]

Source link