[ad_1]

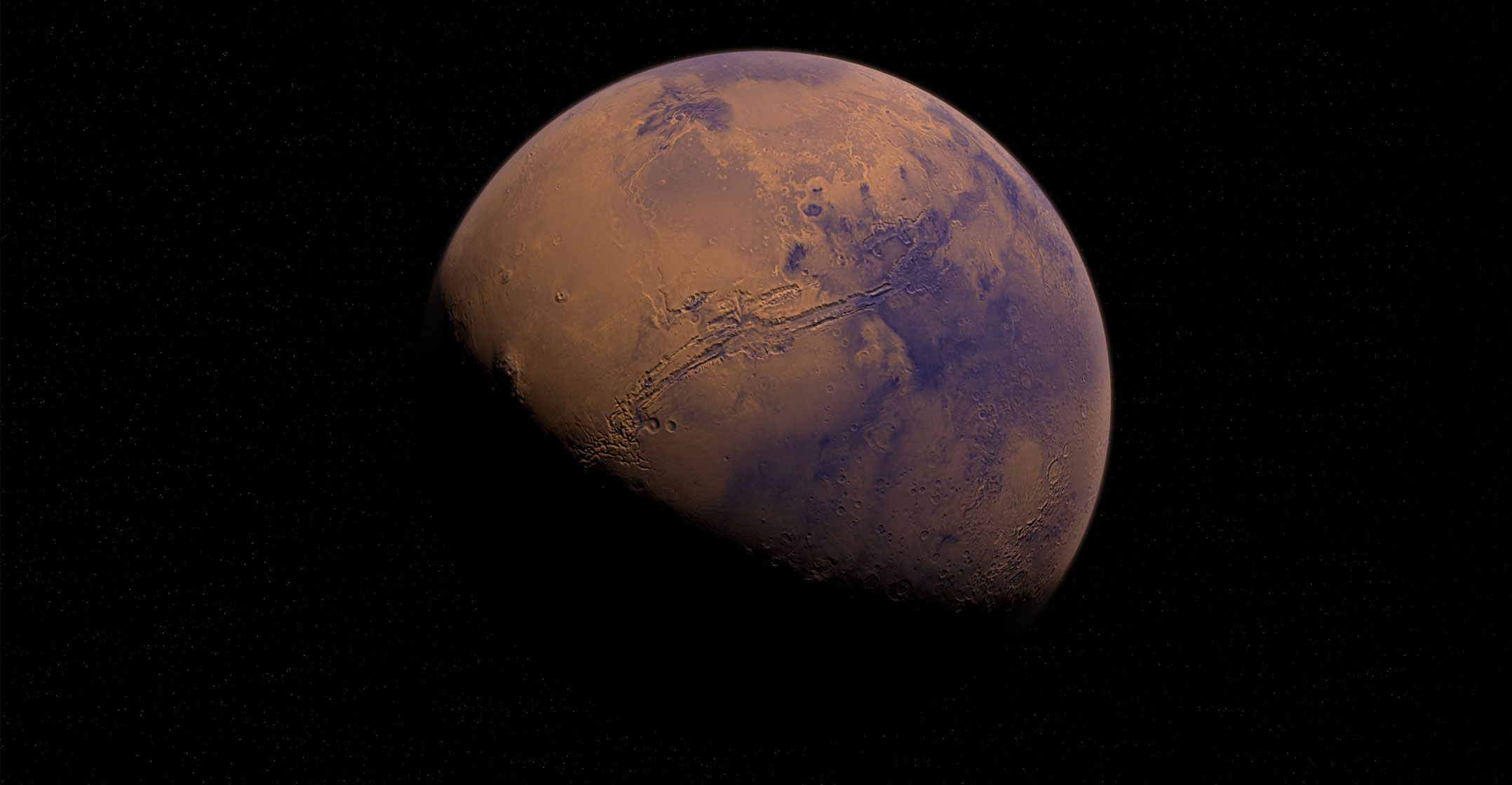

We now know that there is permanent liquid water on Mars, according to an article published Wednesday in the journal Science . This new discovery comes from research using the Mars Express spacecraft that orbits around the red planet since December 25, 2003.

Marsis (Mars' advanced radar for underground and ionospheric sounding) is one of the instruments carried by Mars Express, Through observations covering a four-year period, a team of Italian researchers discovered a large saltwater lake, buried 1.5 km below the southern polar cap of Mars. . This lake is at least 20 km long and seems to be a permanent feature

The reason people are excited about this discovery is because on Earth, wherever you find liquid water, you find life. NASA has long embraced a philosophy of "following the water" in its astrobiological research program – trying to answer the question: "Are we alone?"

In the past two decades we have seen mission after mission. Some, like Mars Express, are orbits, while others (like the incredible Spirit and Opportunity) are rovers. A unifying theme throughout these missions was their attempts to see if Mars had the right conditions for life to exist and prosper.

Thanks to them, we found plenty of evidence that Mars was once hot and humid. We also have evidence that liquid water can still be found on the surface of Mars from time to time.

But until this week, the evidence of modern water points to fleeting moments – droplets condensing on the Mars Phoenix liner; In comparison with today 's discovery, these earlier discoveries are a drop of water in the ocean

The latest observations reveal something remarkable: a salt lake buried deep beneath ice. seems to be a permanent feature rather than a transient phenomenon.

Life?

The comparison that comes to mind is the myriad of lakes buried under the ice of Antarctica. Until now, more than 400 of these lakes have been found beneath the surface of the frozen continent.

The best known is perhaps Lake Vostok, one of the largest lakes in the world, buried and hidden. But the one I want to call attention to is Lake Whillans.

Whillans Lake is buried some 800 meters under ice in West Antarctica. In 2013, a team of researchers managed to drill in the lake and collect samples. What did they find? In other words, the best terrestrial analogues for the newly discovered Martian Lake are not only habitable, they are inhabited . Where there is water, there is life.

Finding this new lake, buried under the South Pole of Mars, is another exciting step in our discovery of the Red Planet. Could there be life there under the ice?

The short answer is that we still do not know. But it seems like the perfect place to look. What we know is:

- Mars was once hot and humid, potentially with oceans, lakes, and rivers

- On the Earth, where you find water, water, you find life

- the transition from hot and humid Mars to the cold and arid Mars that we see today has occurred over millions of years; and

- Life adapts to changing environments, as long as this change is not too fast or dramatic.

What do we get if we put it all together? It is there that things become speculative. But let's imagine that in the distant past, Mars had life. Perhaps life was born here, or maybe it was delivered from the Earth, hitching a meteorite.

Once life is established, it is incredibly difficult to get rid of it. For millions of years, Mars has been cooling down and its water is locked up in permafrost. Its atmosphere has thinned and it has become the red planet we see today.

But perhaps, perhaps, that life could have followed the water – move underground, where she could have found a niche, in a dark and salty lake, buried under the ice of the polar cap south of Mars.

It's quite speculative, but it shows the kind of thinking process that has guided our continued exploration of Mars in recent decades.

Now that we know for sure that there is a reservoir of liquid water just beneath the surface of the planet, astronomers around the world will be thinking of ways to get down to that water to see what Who is here.

It's easier said than done. Landing on Mars is a challenge in the best case, and the vast majority of missions so far have landed at about 30 degrees latitude from the equator of Mars. The two exceptions are the Viking 2 and Phoenix landers, both of which landed in the northern lowlands of Mars.

In addition, landing in the southern hemisphere of Mars is even more difficult. The north is made up of lowlands and the atmosphere there is significantly thicker and the surface smoother (as befits, potentially, at the bottom of an old ocean).

To the south, you have less atmosphere to slow your descent and a rougher surface to make your landing harder.

But, although difficult, it is not impossible. And now we have a huge motivation to try

It would not be surprising that, in a decade, we were seeing missions designed to visit the South Pole of Mars and descend to this great lake, to see what 's going on. hides there. ] The Conversation "width =" 1 "height =" 1 "/>

- Written by Jonti Horner, Professor of Astrophysics, University of South Queensland

- This article was originally published on The Conversation

Source link