[ad_1]

A year after the low-wage strike and high health care costs, teachers in West Virginia faced an omnibus bill that would introduce charter schools and education savings accounts as part of a the reform of public education.

Jarrad Henderson, USA TODAY & # 39; HUI

DELBARTON, West Virginia – The coal miner's son had studied the difficult history of his county's work, wrote his thesis on it and taught the subject to his high school students.

Now, Eric Starr, who knew the story was never repeated, felt the story doing just that. And he was part of it.

In front of a secret meeting similar to that organized by the striking miners a century ago, dressed in black, with the exception of a red bandana similar to the one worn by these minors, he urged his fellow teachers public schools to challenge the governor and their own unions and to remain on strike. .

"I will not go back," he said. "We are complete!"

Eric Starr is one of many teachers who helped direct the strikes out of Mingo County in West Virginia. A year later, little has changed. (Photo11: Jarrad Henderson, USA TODAY & # 39; HUI)

It was last winter. Teachers in Mingo County – with no legal right to strike, no encouragement from their union and little chance of victory – were the first in West Virginia to vote for their health care plan and their remuneration.

The walkout of one day has spread.

On February 22, 2018, West Virginia teachers went on strike, sparking a move that spread to other red states, including Oklahoma and Arizona, and then this year to Los Angeles and Denver. On Thursday, teachers plan to strike in Oakland, California.

But the West Virginia teachers strike of 2018, which has changed so much at the national level, has not changed much since the beginning. On Tuesday, teachers in West Virginia again staged a strike – just to maintain the status quo.

Starr sees the irony.

"I like to see what's happening elsewhere," he says. He is 28 years old, in fourth year of teaching. "But West Virginia can be a slow place to change."

When the 2018 strike in West Virginia ended on March 7, it seemed like a great victory for public school teachers, who were widely blamed for the failures of American schools, and especially for schools in Virginia. West.

But history, even when it repeats itself, is not so simple. The legacy of the 2018 strike is still uncertain.

- The state's promise to provide a source of funding for health insurance for public sector employees – the main subject of the strike – has not been honored.

- Despite a 5% increase, teachers' salaries remain well below those of neighboring states, a difference which explains why the year started with 700 vacancies in classrooms, or 4% of the workforce. State teacher.

- The colony did not increase the number of school specialists, such as counselors and nurses, to help students from families affected by the opioid epidemic in the state.

- During the strike, the teachers' wish to "remember November" only gave mixed results. The Republicans, most of whom opposed the demands of teachers, kept control of both Houses in the Legislative Assembly. This year, they relaunched the proposals that helped trigger the 2018 strike. Teachers and service staff went on strike again.

Tuesday's walkout shut down schools in almost every West Virginia county and lawmakers have ruled out the law on education. It's a win for teachers.

But, say the teachers, they are still waiting for the kind of policy that would show them respect. Wary of GOP state leaders, teachers are again on strike Wednesday to prevent lawmakers from reviving the bill in question. Almost all schools are closed.

Teachers in America: No matter where they work, they experience a lack of respect

Jennyerin Steele Staats, Jackson County Special Education Teacher, is holding her placard outside the West Virginia Capitol on the fourth day of statewide walkouts in 2018. (Photo11: Craig Hudson, Charleston Gazette-Mail via AP)

"We are talking about a strike"?

If the strike last year was not revolutionary, it was remarkable.

At a time when organized labor seems to be in permanent decline, a national movement of public school teachers has emerged in the mining basins of southern West Virginia, one of the most remote corners and more conservative of America.

At a time when political partisanship peaked – and despite the democratic nature of teachers' unions – the strike united Clinton and Trump voters. It was a political unicorn: a "liberal" cause advocated by the Conservatives.

But it was not an anomaly. Here, children grow up as a result of battles between miners and mining companies under the name "Bloody Mingo". Many teachers who went out were the first on picket lines when they wore diapers.

Yet these old passions may not have been revived without a weapon the miners had never benefited from: social media.

On January 6, 2018, a teacher posted an innocent question on a Facebook page: "Just curious if it's a question of strike."

Soon, we spoke only of few other things.

Survey: Even when teachers are on strike, Americans give them good grades. Unions are worse.

Welcome to the mountain state

Jay O'Neal is an undergraduate social studies professor who moved to West Virginia in 2015. After his first year, he realized that because of the rising costs of health insurance, he would win $ 450 less than the previous year.

Teachers across the country lost ground economically during and after the Great Recession, as states cut spending on education. West Virginia, whose coal industry collapsed, ranked 48th in teacher salaries before the strike, according to the National Education Association.

However, teaching in West Virginia has become more difficult as students need more and more, partly because of the opioid crisis. Many live in a household without a biological parent, and teachers sometimes have to find ways to feed the children on weekends or to recover their electricity. One of O'Neal's students found his father with a needle sticking out of his arm, who died of an overdose.

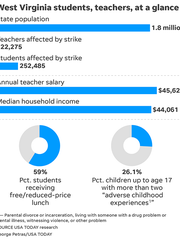

West Va (Photo11: usat)

O 'Neal was not born in the "strike culture" of West Virginia. However, in October 2017, he launched a group page on Facebook to unite members of the West Virginia Education Association's two largest teachers' unions, the West Virginia Education Association and its rival, the West Virginia Federation of Teachers. .

His timing was propitious. The public health insurance agency of state employees had announced a new series of measures to reduce costs. One of the premiums for family coverage on the total household income, rather than the teacher's. Another program was a wellness program that would effectively penalize people who do nothing, such as providing personal biometric data, going to the gym, or wearing an activity monitor such as a Fitbit.

The program was anathema to the people of western Virginia, famous and independent. What affair does he have of certain bean counters what does my wife do? Or what do I weigh?

O'Neal heard a lot of grunts in the teachers' room, but little or nothing in public or on Facebook. The page of his teachers had only about 1,000 members. "I do not understand," he said to a friend. "Nothing happens."

It was as if "strike" was a dirty word. "Everyone thought about it," recalls Eric Starr. "Then, someone worked hard to say it."

Strike fever

This person was Rachel Kittle, a 32-year-old special education teacher originally – not surprisingly – from the mining basins. She did not feel brave, though. The strike was just what she and her colleagues were already talking about.

Shortly after its January 6 publication – "Struggle Discussions?" – O'Neal got a friend's message: "Have you checked Facebook?"

There was Kittle's request, followed by an explosion of comments. The first was disdainful: "Unions are terrified and teachers are reluctant." But there were other voices:

- "Not all teachers."

- "The cuts will not be finished until a line has been drawn."

- "As long as you take it without protest, they will continue to give it to you."

- "Teachers went on strike in 1990. How did it get organized?"

Soon, O 'Neal could no longer keep pace with requests to join the group.

The strike fever exploded after Governor Jim Justice, who had been elected Democrat with union backing before becoming a Republican, supports Trump, proposed a 1% increase only in his speech on the state of Washington. l & # 39; State.

Dale Lee, president of the WVEA union, felt compelled to address the subject at a rally organized on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Teachers waiting for a call to the barricades were disappointed.

"I've heard a lot of people say," It's time to step down, it's time to go on strike, "said Lee." This is not the first step in what we should be doing to reach our goals. "

But it was a battle in which union leaders would be supporters.

It started in the mining basins

On January 23, teachers in Mingo County were the first in the state to decide not to go to school for a day to travel to the state capital to protest. They called it "Fed Up Friday". Several other counties in the southern mining basin quickly followed suit.

Without the right to strike or to bargain collectively, teachers' unions had exercised more pressure on state officials who set the allowances of their members than confronted them. Now they have struggled to catch up with the base. A WVFT official told the Charleston Gazette-Mail that the union did not know how many counties had decided to withdraw, but sent staff to county meetings "to find out what was going on".

Friday Fed Up, teachers from the mining basins gathered in the capital's Rotunda in Charleston to protest. While they were singing, colleagues from the state were watching.

A month later, on February 22, after another day off and a statewide strike vote, 20,000 teachers were released.

Chronology: How has the West Virginia Teachers Strike of 2018 evolved?

The school was closed in 55 counties. Superintendents, already facing a shortage of teachers, did not have enough subcontractors to hold their courses. Teachers would never lose a day's pay.

Public opinion seemed with the teachers. When the Attorney General stated that the strike was illegal and offered to go to court on behalf of the county school boards, he did not receive any attorney.

Five days after the strike began, the governor and union leaders who negotiated announced a settlement, including a 5% increase. They told the teachers to return to work two days later, on March 1st.

But the Republican leaders of the Senate had not signed; the base was not consulted; and teachers pointed out that the governor was a coal company owner. "We were not going to stick to the word," Kittle recalls. Teachers outside the capital chanted: "Back to the table!" And "We were sold!"

At county meetings such as Mingo, where Eric Starr spoke, the base agreed. They were not going back – they were going wild cat.

Strikes spread

Meanwhile, in Arizona, a teacher by the name of Noah Karvelis had created a Facebook page like that of West Virginia. Most of his colleagues supported a strike in their country, he tweeted, "especially with … the success of WV."

He created a Facebook event inviting Arizona teachers to wear red: "West Virginia shows the nation what happens when teachers show solidarity."

Finally, the Republican Senate of West Virginia has accepted a 5% increase for all state employees. And the governor promised to freeze health insurance premiums for 18 months; create a working group to find a source of funding dedicated to health insurance; and to waive higher costs for workers who have not complied with the welfare plan.

On March 7, after nine days of school canceled, teachers returned to class.

But teachers from other states have begun to withdraw. April 2, Oklahoma and some counties of Kentucky; April 26, Arizona; April 27, Colorado. On May 16th, teachers from North Carolina organized a demonstration of a walkout and rally day.

Mariana Tovar, an Arizona teacher, applauded the walkout organized by RedforEd at the Phoenix State Capitol on May 3rd. (Photo11: Cheryl Evans / The Republic)

A half empty glass?

A year later, it's easy to point out what the West Virginia teachers' strike did not do.

The increase, which averaged $ 2,000 per teacher, made little difference to life. It allowed teachers to pay bills or loans, or perhaps to buy a car. But their colleagues continue to flee to the highest paid districts of other states. Mingo High School, for example, has been trying since May to replace the director of his choir, who left Ohio for a similar position, paid $ 10,000 more. Nobody even applied for the vacant position.

With regard to health insurance, the governor proposed $ 150 million in the state budget to stabilize employee costs. However, no agreement has yet been reached on how to isolate this funding from the annual budget process.

The political legacy of the strike is not clear either. Some criticize teachers for not having mobilized enough parents and friends to vote; Some say that the teachers themselves did not come in enough numbers, which rekindled the memory of the pre-strike complacency that frustrated activists like O'Neal.

Whatever the cause, the teachers' failure in November to elect more members to the Legislature came back to haunt them this year.

To abolish legislation that had not even been passed, teachers had to go on strike again. They won a victory by ensuring that their situation does not get worse. But that did not improve either.

Teachers and school staff celebrate at the West Virginia Capitol after the House of Delegates voted Tuesday to defeat indefinitely a controversial education bill. (Photo11: Craig Hudson, AP)

The former miners went on strike against the mine owners. Today, teachers are on strike against taxpayers, whether personal or commercial. Taxpayers are voters and voters say that they are for higher salaries of teachers. They also say they are against raising taxes.

Talk about the nation

In a sense, the strike has not so much revived history as reversed it.

With the fall of coal, a region once renowned for its sometimes criticized independence has become synonymous with a fatalistic acceptance of the status quo and dependence on welfare, ranging from food vouchers to the disability benefit.

The strike, however, has put West Virginia at the forefront of the middle class.

Robin Ellis, a teacher at Mingo Central High School, is Republican, but she has helped lead strike teachers in West Virginia. She is the daughter of a retired 83-year-old who has gone on strike several times. (Photo11: Jarrad Henderson, USAT)

No one personifies this reversal more than Robin Ellis, a Mingo High English teacher who is also a grandmother, a social-conservative, a Republican and one of the 69% residents of West Virginia (and 83% of Mingo residents). who voted for Donald Trump against Hillary Clinton in 2016.

She is also the daughter of a former 83-year-old trade unionist who went on strike several times.

During the strike last year, Ellis got up on the main street of his city to denounce the motorists and, as the traffic, plead for the teachers. And, like young Eric Starr, she stood up at a meeting after the agreement in principle to entice her colleagues to stay out.

She said the strike was more than money or respect. It was an obligation to past generations. "The word" strike "makes us want something," she says.

"I do not think my father has ever been more proud of me."

Read or share this story: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/education/2019/02/20/teacher-strike-west-virginia-school-closings-education-bill/2848476002/

[ad_2]

Source link