[ad_1]

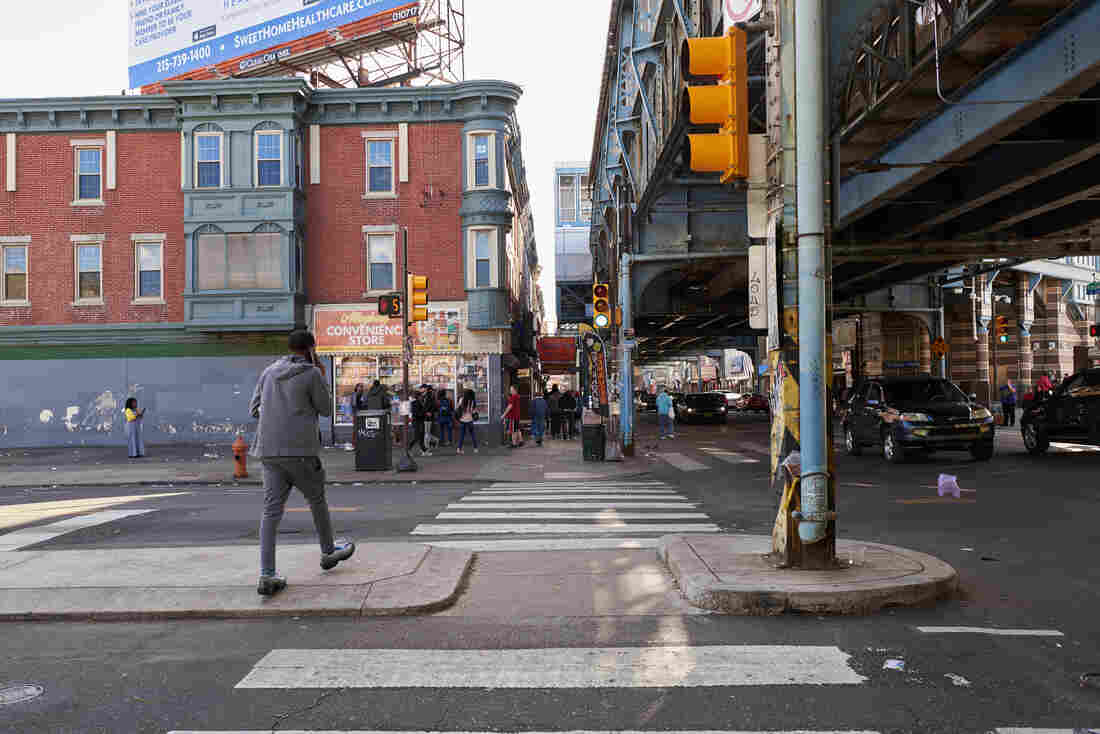

Safehouse plans to settle in this block of Hilton Street, in the Kensington section of Philadelphia. The proposed facility would allow drug users to inject under medical supervision. The neighborhood is known for its drug use.

Natalie Perserchio for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Natalie Perserchio for NPR

Safehouse plans to settle in this block of Hilton Street, in the Kensington section of Philadelphia. The proposed facility would allow drug users to inject under medical supervision. The neighborhood is known for its drug use.

Natalie Perserchio for NPR

A nonprofit group based in Philadelphia is fighting in court to open the country's first facility so that people can use illegal opioids under medical supervision. The group, called Safehouse, has the support of the local government, but federal prosecutors face a court challenge.

The idea behind supervised injection sites is to provide people with a space where they can use drugs under the supervision of qualified medical personnel, who are prepared with naloxone, a drug that reverses the overdose. These sites provide needles and other clean supplies, but users bring their own medicines.

Once people have finished using drugs, staff can talk to them about access to treatment, legal advice, housing and other social services.

"If you find a place that accepts drug use while providing you with non-judgmental services, you'll start to trust them," says Ronda Goldfein, Safehouse's vice-president co-founder. "And once there is a relationship of trust, you are more inclined to accept the range of treatment that they offer, including recovery."

Ronda Goldfein, vice president of Safehouse and executive director of the Pennsylvania AIDS Law Project, in her home in Philadelphia.

Natalie Piserchio for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Natalie Piserchio for NPR

Ronda Goldfein, vice president of Safehouse and executive director of the Pennsylvania AIDS Law Project, in her home in Philadelphia.

Natalie Piserchio for NPR

Supervised injection sites operate in Canada, Europe and Australia, but have never officially opened in the United States. The group that runs Safehouse hopes to launch its site this year.

Opioid overdoses – especially of very potent fentanyl – continue to increase throughout the country. Health authorities in several other cities, including Seattle, New York, and Denver, and elected officials in Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Jersey have reviewed similar proposals for injection sites.

But US District Attorney William McSwain is trying to stop them

"These are people with good intentions," says McSwain. "These are people who are doing their best to fight the epidemic, but we think this step of opening an injection site is a step that crosses borders."

McSwain and the Trump administration sued Safehouse in February. Prosecutors cited so-called "crack house" laws that make it a criminal offense to own a property where drugs are used.

In response, Safehouse convened a team of a dozen volunteer lawyers and earlier this month commenced a lawsuit against the government in federal court in Philadelphia, thereby establishing a dispute which, according to the legal experts, is likely to test the limits of the law.

Safehouse's legal team states that the drug laws of the 1980s were never intended to apply to a medical facility in the midst of a public health crisis.

"Safehouse is nothing from a" crack house "or a" rave "to the drug.Safehouse has also not been established" for the purposes "of illicit drug use." , the complainant, Ilana Eisenstein, said in her document, writing that the federal law cited by prosecutors, the Controlled Substances Act "does not regulate medical treatment or the practice of medicine".

The lawyers of the association also maintain in court documents that the closure of the proposed injection sites would violate the Judeo-Christian beliefs of the group on the "preservation of life", thus violating the law on the restoration of Religious Freedom, a 1993 federal law that protects people from the exercise of their functions. Faith.

"[This] the service is an exercise of the religious convictions of its board of directors, whose fundamental principle is to preserve life, provide shelter for neighbors and serve the people who most need physical and spiritual care, "wrote Eisenstein at the court.

Lawyers compare the vital potential of a supervised injection site to how syringe exchanges have helped reduce the number of deaths during the AIDS epidemic.

"If we feel it's in our power to make that happen or if we try, we owe it to everyone we've lost," Goldfein said.

Due to the legal uncertainty surrounding supervised injection, most efforts to open such sites in the country have become bogged down.

The legal confrontation with the federal government was not a surprise. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein told NPR last year that if efforts were made to open a supervised injection site, the reaction would be quick and aggressive.

"If local governments engage in the facilitation of drug use, they actually invite people to bring these illegal drugs into their business premises," Rosenstein said in August. "If you start down this path, you will really undermine the deterrent message that I feel is so important to keep people from becoming addicted in the future."

In Philadelphia, senior officials, including the mayor and prosecutor, approved the injection site proposal.

"I am a public health official whose job is to prevent unnecessary deaths," said Tom Farley, health commissioner in Philadelphia. "The evidence is clear that these facilities save lives, while serving as an entry to addiction treatment."

However, city officials said that no public funds would be spent on opening facilities. Instead, Safehouse is the only one to raise private funds, which the members of the non-profit association say continue to do despite the opposing battle.

The two parties involved in the lawsuits agree on one point: the result depends a lot.

Whatever the court decides in this case, it could spread throughout the country, opening the way to injection sites or possibly blocking them permanently.

"You know, it's something that people will consider as a test case that will have implications in other districts," McSwain said.

The court is not the only hurdle that Safehouse faces in anticipation of its opening this year.

Outside the Allegheny station in the Kensington section of Philadelphia. The neighborhood is home to open-air drug markets. Its residents have mixed feelings about the idea of a safe injection site.

Natalie Piserchio for NPR

hide legend

activate the legend

Natalie Piserchio for NPR

Outside the Allegheny station in the Kensington section of Philadelphia. The neighborhood is home to open-air drug markets. Its residents have mixed feelings about the idea of a safe injection site.

Natalie Piserchio for NPR

Political resistance also increased at the Philadelphia City Council, fueled by the opposition of its neighbors.

"It's ridiculous what they're even trying to do," said Joe Capriotti, a resident, at WHY. Capriotti lives not far from a site envisioned by Safehouse. "It's all wrong with that."

In the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia, one of the country's largest open-air drug markets, an opioid user named Joe is also waiting for the decision.

Joe is only identified by his first name since he uses illegal drugs. He is 35 years old, lives in New Jersey and sells mortgages for a living. He has already been treated, but has recently relapsed. And he says that dangerous synthetic opioids are inexpensive and easy to obtain in Kensington.

"It's sad to see people dying, dude … I've had so many friends who were dying and so many people who are on this … they are not the same person." I am not the same person, "he says.

Joe stands among needles thrown right in front of a building that Safehouse plans to move into. Above the din of a noisy train platform nearby, other users are chatting gently with him before injecting drugs into his arms, a few steps away from police officers. city patrolling the neighborhood.

Joe says that he is almost dead from an opioid overdose. If the injection site opens, he states that he will quickly become one of his clients.

Currently, he and his friends are using drugs in abandoned buildings, driveways, and fast-food washrooms where fatal overdoses can occur quickly without anyone helping them. It would be so much better, he says, to have medical staff at his side.

"I think it will save lives, not take them," he said.

[ad_2]

Source link