[ad_1]

Start a conversation about Donald Trump these days and it’s only a matter of time before someone mentions Adolf Hitler.

But if your subject is Hitler, how long before someone brings up Trump? Two minutes is enough for the film The Meaning of Hitler, a study of our eternal fascination with the Nazi dictator by Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker.

“We might as well address his similarities to Trump,” says interviewee Martin Amis, the British novelist, identifying at least three: undermining state institutions to magnify their own position; fanatical cleanliness; layer.

The documentary then switches to a clip of Jewish comedian Sarah Silverman playing Hitler on late night television, with a toothbrush mustache and a uniform, saying of Trump, “I agree with a lot of things that I do. he says, a lot. Like 90% of what he says I’m like, this guy gets it!

Trump has been moving up the autocrat analogy rankings for some time. In 2015, South African comedian Trevor Noah, new host of Comedy Central’s The Daily Show, described him as the perfect African president, referring to Idi Amin from Uganda, Robert Mugabe from Zimbabwe and especially Muammar Gaddafi from Libya.

Elsewhere, comparisons have been made with Latin American populists like Hugo Chávez of Venzuela. And when Trump returned from coronavirus treatment in hospital last year and removed his face mask in a macho display on the White House balcony, the tribute to Italian fascist Benito Mussolini was a must for all but him.

But in 2021, it’s spring for Hitler. Last month, Frankly, We Did Win This Election, a book by Michael Bender of the Wall Street Journal, reported that during a visit to Europe to mark the centenary of the end of World War I, Trump told his Chief of Staff, John Kelly: “Well, Hitler did a lot of good things.”

Another book, I Alone Can Fix It, written by Washington Post reporters Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker, tells how General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, compared Trump’s attacks on democracy to the 1933 fire against the German parliament that the Nazis used. as a pretext to consolidate power, telling his collaborators: “This is a Reichstag moment. The Gospel of the Führer.

Germany-born Epperlein and US-born Tucker – a married couple whose previous joint works include Gunner Palace, The Prisoner Or: How I Planned to Kill Tony Blair, and Karl Marx City – are better placed than most for draw such parallels.

Speaking via Zoom from Berlin, a bicycle hanging on the wall behind him, Tucker said: “Obviously Donald Trump is not Hitler and it gets a bit shrill and hysterical at times. It is more important to see what is right in front of us, which can, in fact, be scarier.

“I think of both of us, watching things and meeting some of these experts, it became clear that maybe we should take a closer look at each other and what is unlocked in us.”

Epperlein intervenes: “It’s not about comparing them. It’s more about seeing what happened before in history and what is happening now or in recent years – the normalization of lying, for example.

“It happened 80 years ago and it has happened over the last few years and it’s really scary because we’re all involved in it to some extent and where is it actually leading? This is why it is important to really know your story and also to know these details and what could happen.

Seventy-six years after his death, Hitler remains one of the most famous men in the world and ubiquitous in Western culture. It is the subject of countless books, television documentaries (Hitler’s Zombie Army at 1 a.m. Tuesday on American Heroes Channel was followed by Hitler’s Messiah Complex at 2 a.m.) and dramatic films (Downfall, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and many others). Tucker calls it a “Hitler Industrial Complex” unloaded by self-examination.

He comments: “Obviously, it’s not as if these materials stop the spread of ideology or curb anti-Semitism. If anything, the more they are presented without context, the more they propagate these ideas. It might not be that people are so fascinated with him or that, because there’s something about them that’s kind of unlocked.“

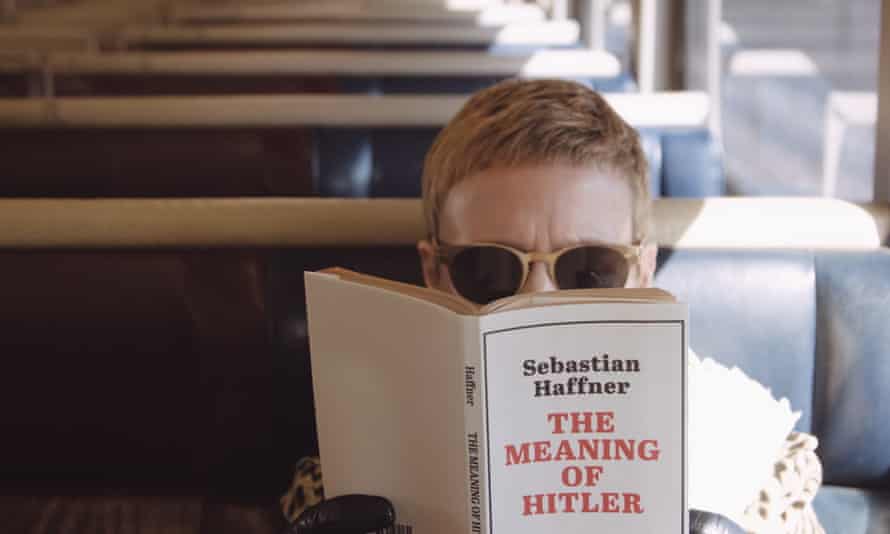

Determined to avoid contributing to the cult of personality, Epperlein and Tucker use excerpts from former Observer journalist Sebastian Haffner’s penetrating 1978 book The Meaning of Hitler as their narrative backbone. They travel to Hitler’s birthplace in Austria, where a stone marker does not mention his name, a parking lot in Berlin that is above the bunker where he committed suicide.

They interview historians and writers including Saul Friedlander, Francine Prose, Yehuda Bauer and Nazi hunters Beate and Serge Klarsfeld as well as a forensic biologist, psychiatrist and sociologist archaeologist looking for clues that could begin to explain how Hitler became Hitler.

But historian Deborah Lipstadt, named last month as the United States’ special envoy to monitor and combat anti-Semitism, tells them: “When we try to understand where Hitler’s anti-Semitism came from, what we are trying to to do is to rationally explain an irrational feeling.

“When people say, ‘Well, her mother was treated by a Jewish doctor and he couldn’t save her,’ so what? The minute you try to rationalize an irrational feeling, you are going to be lost.

The film therefore presents a paradox. To try to understand Hitler is to risk humanizing him and reducing his guilt; but to admit that he defies all understanding is to risk raising him to the rank of superhuman, of making him a modern Lucifer.

Tucker reflects: “On the one hand, the more you try to understand it, the more empathy you have: ‘Oh, poor Hitler.’ And then there is the other part: it is exceptional or it is this break in history. The Holocaust is certainly exceptional, but the conditions that can lead to it certainly exist in all of us, so it is difficult terrain to navigate.

Still, there is a kind of “rosebud” here, a biographical key that unlocks at least some of the thought and power of Hitler and his imitators. Perceived victim.

Epperlein says: “After Germany lost World War I this is of course seen as a victim, and Hitler was able to channel all of this and start it in a way that was simply unprecedented.. “

Tucker adds: “Right here in Berlin this past weekend there were 5,000 Covid deniers lashing out in the streets, backed by some pretty hardcore neo-Nazis and it’s amazing to see the victimization on display. It is as if they are acting as if they are living in a fascist dictatorship. The repetition of this is so revealing. “

Perceived victimization is also at the heart of Trumpism. He gained political ground by telling crowds that they are the victims of cultural, economic and political elites, unfair trade rules and violent illegal immigrants. He consistently portrays himself as a victim of media prejudice and deep state conspiracies such as the Russia inquiry, impeachment and a “rigged” election. His supporters seem delighted with their common community of grievances and feel the revenge has been legitimized.

Epperlein says of Hitler and Trump: “The magic, to a certain extent, is that they are able to give people permission to release their most terrible thoughts and ideas and to express them and do so. all together.

“It makes them feel good, powerful and strong and it can be easily molded into a movement. You see it with Donald Trump and his supporters. You see it here with these Covid deniers because it’s kind of the same thing. It is really dangerous.

Hitler’s Significance includes an interview with discredited British historian David Irving, who is presented with a giant on-screen caption (citing a court ruling) that reads: Neo-Nazism. Irving is seen “guiding” acolytes in Treblinka, an extermination camp in Poland.

The filmmakers debated long and hard whether to give him screen time, but ultimately followed Haffner’s book lead by engaging with him. Epperlein’s narration explains, “You can’t make a movie about Hitler without talking to his greatest admirer. “

Tucker adds via Zoom: “Yeah, you can ignore it completely unless you Google it, it shows up everywhere. He was financially ruined by the Lipstadt affair [in 2000 Irving sued Lipstadt for libel after she called him a Holocaust denier and lost] and yet somehow flourished in this online world, like many other people.

“He’s the grandfather of it all. He found a way to make it profitable, like a lot of other people who are quite marginal and get bigger. At the same time, as the movie shows, people like Mark Zuckerberg [chief executive of Facebook] act like it’s just a case of people getting it wrong when it is deliberate. “

He also acknowledges: “There is a debate to be had. People like Lipstadt would say she believes in free speech, she doesn’t believe Irving should be silenced.

“I also think there should be a healthy and vigorous debate about this, but as filmmakers it was also very important not to fall into the trap: Irving is like a camera magnet, he’s like a candy, he’s so convincing, he’s so twisted. Strangely enough, sometimes you don’t feel sympathetic to him, but you’re like, oh, he’s just an old man and you want to understand him. But he is -“

Epperlein intervenes: “He’s full of hate and he’s a terrible anti-Semite.“

Irving’s meaning, at least, is clear. Hitler, however, seems destined to continue to torment the species that produced him, as unfathomable as demonic. Amis comments, “Our understanding of Hitler is central to our understanding of ourselves. It is a calculation that you must do if you are a serious person.

[ad_2]

Source link