[ad_1]

PArentage is a central part of identity, so the discovery that one does not share a biological connection with one’s mother or father is naturally a shock. Much worse, however, is discovering that the people who created you were monsters of an unforgivably heinous sort – a fate that befell many men and women whose birth mothers sought fertility treatment from Pickaxe. , Dr. Quincy Fortier of Nevada.

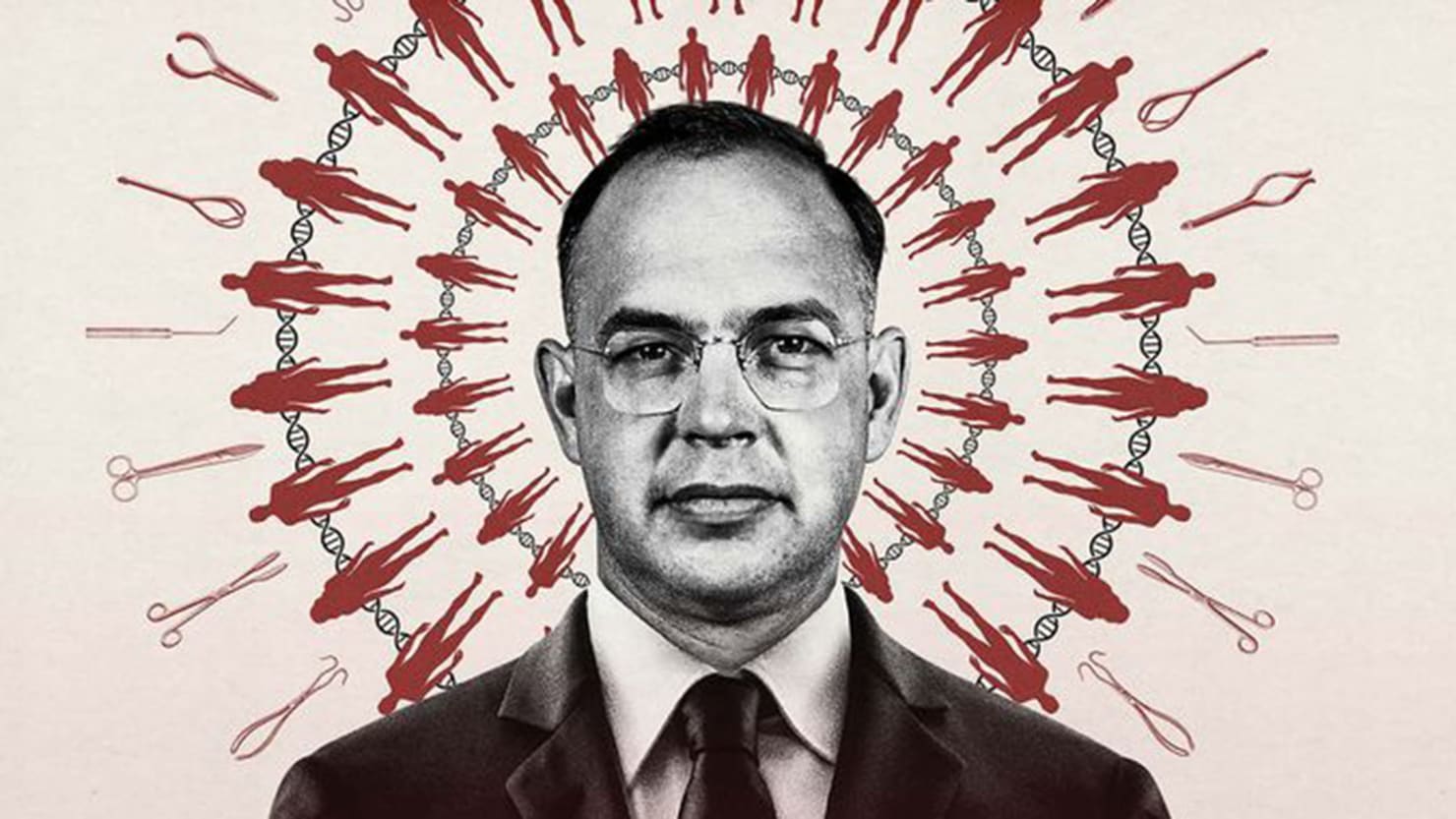

Baby god (premiering Dec. 2 on HBO) is the story of Fortier, who over the decades has infused an unknown number of patients at his women’s hospital. But more importantly, it is the story of some of the children he fathered, none of whom had the slightest idea that Fortier was their father until they attempted to trace their genealogy through DNA kits. from Ancestry.com, or that they were contacted by others who had followed suit and established a previously unknown connection with the doctor. Through their experiences, Hannah Olson’s heartbreaking documentary exposes a legacy not just of biology, but of inherited deception, betrayal and violation, for as it eventually becomes clear, Fortier was not just a moron who surreptitiously implanted innocents with his own sperm – he was a serial pedophile who preyed on his own children, including a stepdaughter he had personally impregnated.

As noted by Brad Gulko, one of Fortier’s descendants, the doctor operated in a pre-DNA era in which the lineage was considered fundamentally unknowable, which made it much easier for men to rationalize the practice of donation. of their own sperm in medical school and – in cases like Fortier’s – to mix their own genetic material with that provided by donors (who were often the husbands of patients). They just thought that no one would ever be able to find out, and therefore the greater good outweighed their duplicity. With DNA analysis now an over-the-counter process, however, such tricks are much more difficult to pull off, and it wasn’t long before Fortier’s subterfuge hit the headlines – and landed him in court. .

Fortier was never put behind bars for his behavior, nor even lost his license, continuing to work until the age of 90 from his home, where he lived with two adopted daughters who he used to do physical exams. routine. One of them refuses to even show her face on camera during interviews, and the other, Sonia Fortier, grimaces admitting that she doesn’t want to know if her father sexually abused her children. previous marriage (she says he never touched her). His son Quincy Fortier Jr., however, is less circumspect about Fortier’s true nature. “My father was crazy. Also, a pervert, ”he declares, explaining that his father assaulted him, each of his four sisters, his younger brother and practically all the other children who came into his orbit. “He wanted to play,” he said with disgust.

Sonia maintains that, “in his mind, he didn’t mean harm,” and assumes that Fortier used his own genetic material to get women pregnant because people don’t care as much about their backgrounds as they do now. In other words, it was justified because people were content to be blissfully ignorant of any biological scams perpetrated against them. This is a pretty weak answer to the question of why Fortier has kept his behavior a secret from his patients, and underlies everything Baby god is the basis for understanding that Fortier’s willful denial of transparency is in itself proof that what he did was wrong – and further, that he knew it was wrong.

Fortier’s saga is hardly unique; Baby godThe coda says more than two dozen US fertility doctors have been accused of secretly impregnating patients with their own semen, and even a cursory Google search results in articles on many related foreign specialists. Olson’s film is less concerned with the ugly global phenomenon of which Fortier is an example, however, than with the human toll of his misery. This seems considerable, considering that conversations with a handful of Fortier’s children (whose number is impossible to calculate, so prolific he was in helping aspiring mothers) are steeped in resentment, fury, grief, and a deep sense of doubt and confusion.

“Olson’s film is less concerned with the ugly global phenomenon of which Fortier is an example, however, than with the human toll of his misery.“

During her investigation of her past with Fortier, Detective Wendi Babst admits that trying to understand how Fortier has affected her present – literally and figuratively – is a painful process, as her mark is everywhere (“It’s like a chain reaction which I can’t really stop “). Mike Otis grapples with the realization that, because Fortier is his father, he is now free from the shame that comes with thinking that his mother’s abusive ex-husband fathered him. For Jonathan Stensland, reckoning with a Fortier pedigree is even more complicated, as his mother was Fortier’s adopted daughter, whom he impregnated during a routine check-up and then sent to a Minnesota single mother house so that she can give up her baby for adoption. . Stensland recounts his subsequent adulthood encounters with Fortier, who offered absurd apologies for how it all turned out – at one point, Fortier allegedly suggested that perhaps it was a “virgin birth” – and the lingering angst of its origins is evident in its confrontational countenance.

“Bad means do not justify ends,” says Fortier’s former colleague, Dr. Frank Silver, towards the conclusion of Baby god, neatly summing up any ongoing debate over whether Fortier had the right to do what he was doing. Nonetheless, even Silver and her OBGYN colleagues at the Women’s Hospital, Dr Harrison Shield, scoff at the fact that by selling their sperm while in medical school, they are also (or could be) the fathers of many descendants, thus revealing their own somewhat casual attitude in this regard. practice.

Olson’s tender, understated non-fiction flick, however, doesn’t take Fortier lightly, detailing through heartfelt testimonials the damage done by the inexcusable con of this unique individual, who has left so many ashamed of their legacy. and their very existence. Baby god opens with footage of the abandoned Fortier Women’s Hospital, where blinds hang, medical supplies gather dust, files are strewn about and paint peeling off the walls, and these views not only turn out to be haunted visions of a crime scene, but also an appropriate visual. metaphors for the wreckage and ruin Fortier ultimately left in its wake.

[ad_2]

Source link