[ad_1]

Now it’s the new vehicles, the restaurants, the energy. Whac-A-Mole play as some price spikes slow down while others begin. But it’s much worse than it looks.

By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) jumped 0.5% in July from June, after jumping 0.9% in June, 0.6% in May, for a three-month annualized rate – the momentum over three months – by 8.1%. Year over year, the CPI jumped 5.4%, the same pace as in June, and the fastest since June 2008 (5.6%), all the fastest since January 1991, according to data released today by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPI excluding the volatile components of food and energy (“core CPI”) rose 0.3% for the month and 4.3% year-on-year.

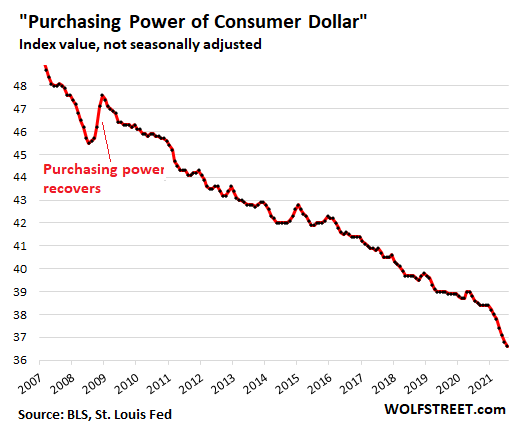

The CPI measures the loss of purchasing power – well, part of the loss of purchasing power, as we will see in a moment – of the dollar of consumption and therefore the purchasing power of labor. In July, that purchasing power fell another 0.5% for the month, and over the last three months on an annualized basis, it has fallen 8.6% – “Honey, where did my big increase go?” “

The CPI greatly underestimates one third of its components: the cost of housing.

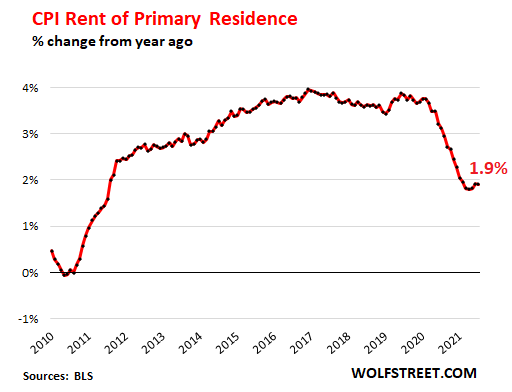

Costs of ownership and rents account for 31% of the CPI. These are the most important categories, the most important categories, but they have hardly changed despite the explosion in housing costs and have thus removed the CPI.

“Rent of the main residence”, which weighs 7.6% in the overall CPI, only rose 1.9% year-on-year despite the chaos in the rental market as many cities saw double-digit rent increases, while that others have experienced declines. Every month this year it has grown 0.2% from the previous month as if nothing had happened. This is the CPI of rents, which fell from the range of 4% in 2019 to 1.9%:

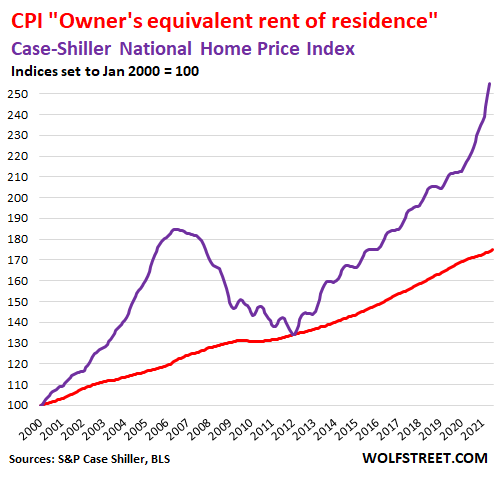

“Equivalent rent owner of residences” – the component that tracks the costs of homeownership and weighs 23.6% in the overall CPI – only increased by 2.4% year-on-year despite the historic price explosion in the housing market .

The property component of the CPI does not track actual home price inflation, but is based on surveys that ask what homeowners think about their homes could rent for and therefore is a measure of the rent as received by the landlord.

Meanwhile, back at the ranch, the national median price of existing homes increased 23.4% year-over-year, according to the National Association of Realtors.

The Case-Shiller Home Price Index, which tracks changes in the price of the same house and therefore is a measure of house price inflation, peaking at 16.6% year-on-year, the highest in data going back to 1987 (purple line). And yet, the BLS homeownership expense measure barely budged (red line):

Energy costs climbed 23.8% year-on-year.

Energy represents 7.2% of the overall CPI. The spike was brought on by gasoline, a surprise to anyone who recently refueled, which jumped 41.8% year over year. Natural gas jumped 19% year-on-year. The home electric service CPI increased 4.0% year over year.

Durable goods inflation climbed 14.3% year-on-year, the highest in June since at least 1957.

Crazy prices for new and used vehicles drove the CPI for durable goods up, so to speak. Other items in this category are home appliances, consumer electronics, furniture, tools, bicycles, sports equipment, etc. The durable goods CPI rose 14.3% year-on-year, after rising 14.6% in June, two of the biggest jumps in the data dating back to 1957.

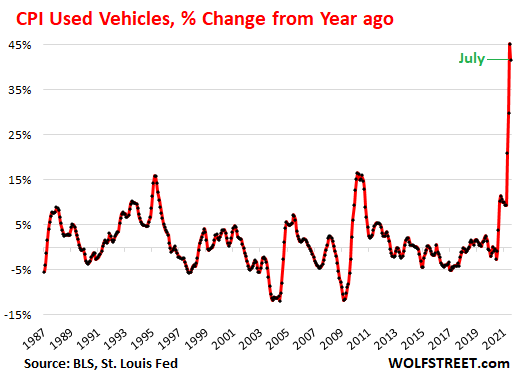

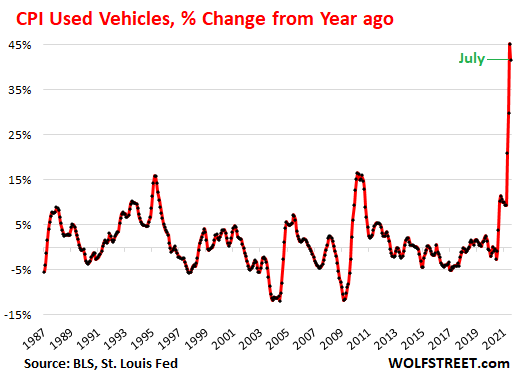

The used vehicle CPI jumped 0.8% in July, but given the crazy peak that started last summer, the july jump was much smaller than the july jump of last year. And year on year – because of this base effect – it increased a little less than in June, but still staggering 41.7%. Not much comfort for used vehicle buyers yet, but price resistance has finally started to emerge and part of this crazy price spike will ease off:

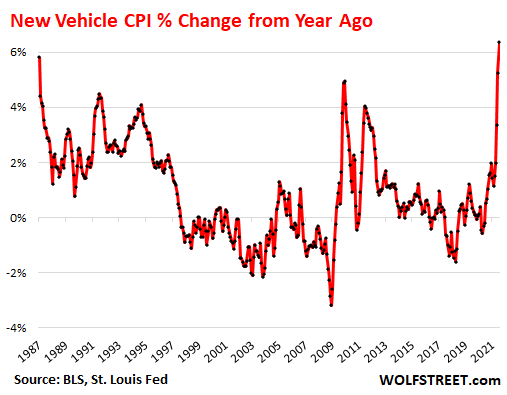

The CPI for new vehicles increased the most since 1982, even as the peak in the used vehicle CPI slows. It’s the Whac-A-Mole inflation game, where one price spike here is replaced by another price spike there.

The CPI for new cars and trucks jumped 1.5% in July, the third consecutive month of these types of price spikes, the largest since the cash-for-clunkers program during the Great Recession. This brought the year-over-year peak to 6.4%, the fastest since January 1982. But as we’ll see in a moment, that price spike is underestimated by “hedonic quality adjustments.” “.

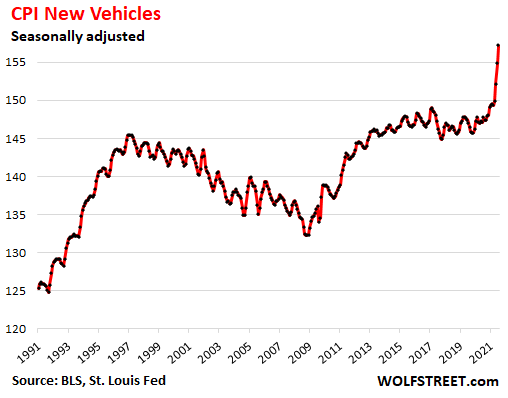

“Hedonic quality adjustments” remove CPIs for new and used vehicles. The BLS uses “hedonic quality tweaks” to account for improvements made to vehicles over the years. For example, the estimated additional costs of the decades-long transition from a four-speed automatic transmission to an electronically controlled 10-speed transmission are removed from the CPI at every step of the way. To illustrate what that means, here is my price index for the F-150 and Camry in the real world compared to this CPI for new vehicles dating back to 1989.

In theory, the CPI measures changes in the price of the same item over time; and any improvement changes the article, which then comes down to a price increase based on an improvement rather than just the loss of the purchasing power of the dollar. In theory, this makes sense.

In practice, these hedonic quality adjustments have been applied aggressively to lower the CPI and thus remove the appearance inflation. Underreporting the dollar’s loss of purchasing power is a convenient political thing, an effort to keep workers in the dark about the purchasing power of their labor.

The effect can be seen in the New Vehicle CPI as an index, which shows that new vehicle prices have fallen in the years since the hedonic quality adjustments took effect, and that 2019, you could have bought a Camry or an F-150 for the same price. price as in 2000, which of course is a total farce. It wasn’t until the recent spike that got past the hedonic quality adjustments, but it will eventually be dragged down by them as well.

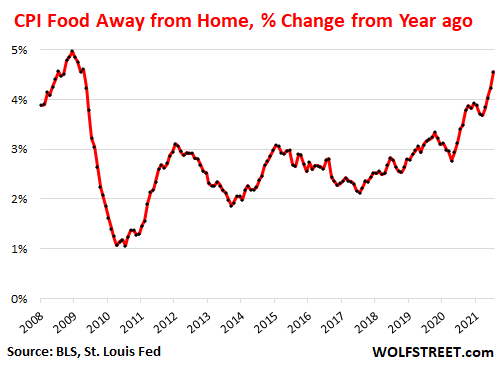

Restaurant prices are next in Whac-a-Mole inflation.

Anyone who has eaten at restaurants or followed the announcements of fast food chains knows that this has happened, and it is now very gradually fitting into the “Food away from home” CPI, which has jumped. 0.8% in July to June, after jumping 0.7% in June and 0.6% in May. Year over year, the index is up 4.6%, the highest since 2009. But that’s just the beginning.

Restaurants, which are struggling to hire workers, have increased their wages, and they are also facing increases in the costs of the products, ingredients, and services they use, and they are facing operating costs. higher due to the pandemic, and they began to pass these costs on to consumers:

This loss of purchasing power is “permanent”.

Only a period of deflation – with a general fall in prices – would make it possible to recover the purchasing power of the dollar. But that will not be allowed. In my lifetime, there were only a few quarters of deflation. The rest of the time it was either inflation or runaway inflation. And now, after a period of inflation, we have runaway inflation. As the first graph above shows, the loss of purchasing power is not “transient” or “temporary”, but permanent and unwavering. What is transitory is the rate of future losses in purchasing power.

Do you like reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? Use ad blockers – I totally understand why – but you want to support the site? You can donate. I really appreciate it. Click on the beer and iced tea mug to find out how:

Would you like to be notified by email when WOLF STREET publishes a new article? Register here.

![]()

Watch our sponsor, Classic Metal Roofing Systems, discuss the benefits of using the products they manufacture.

Product information is available from Classic Metal Roofing Systems, manufacturer of beautiful metal roofs.

[ad_2]

Source link