[ad_1]

Prosthetic limbs improve each year, but the strength and accuracy they gain does not always translate into easier or more effective use, as amputees have only a basic level of control. Swiss researchers are studying a promising track: manual control by the AI.

To visualize the problem, imagine a person whose arm is amputated above the elbow and who controls a smart prosthesis. With sensors placed on their last muscles and other signals, they can easily raise the arm and direct it to a position where they can grab an object on a table.

But what happens next? The many muscles and tendons that would have controlled the fingers are gone, and with them the ability to feel exactly how the user wishes to bend or extend their artificial fingers. If all the user can do is signal a generic "catch" or "release" that loses a huge amount of what a hand is actually good.

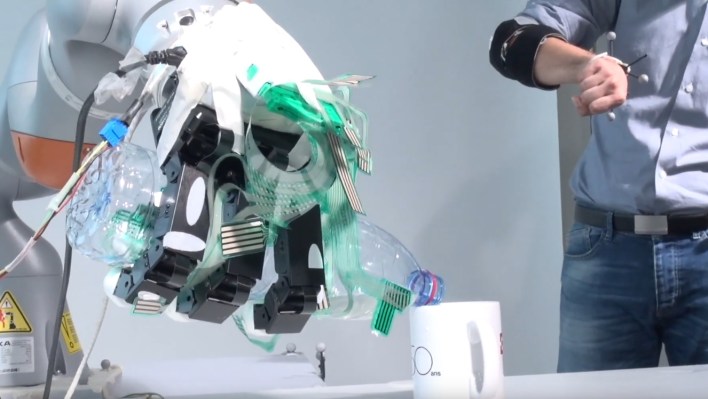

Here, researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) take control. Being limited to saying hand grabbing or releasing the hand is not a problem if the hand knows what to do next, as if our natural hands were "automatically" the best grip for a hand. object without us having to think about it. Robotics researchers have long been working on the automatic detection of grasping methods, and this solution is perfectly suited to this situation.

<img class = "aligncenter size-full wp-image-1881509" title = "epfl_roboarm" src = "https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/epfl_roboarm.gif" alt = "epfl roboarm” width=”640″ height=”412″/>

Prosthesis users form an automatic learning model by asking them to observe their muscular signals while trying different movements and seizures in the best possible way without the real hand. With this basic information, the robotic hand knows what type of input it should try. By monitoring and maximizing the contact area with the target object, the hand improvises the best grip in real time. It also offers resistance to falls, being able to adjust its grip in less than half a second if it starts to slip.

The result is that the object is grasped firmly but gently as long as the user continues to grasp it, essentially with his will. When they have finished with the object, after taking a sip of coffee or moving a fruit from a bowl to a dish, they "free" the object and the system detects this change in the signals of their muscles and makes even.

This looks like another approach, that of students in the Microsoft Imagine Cup, in which the arm is equipped with a camera in the palm of the hand that gives him information about the object and how it should grab it.

Everything is still very experimental and done with a third robotic arm and software not particularly optimized. But this "shared control" technique is promising and could very well be fundamental for the next generation of smart prosthetics. The article of the team is published in the journal Nature Machine Intelligence.

[ad_2]

Source link