[ad_1]

Interest rate cuts in the United States are aimed at mitigating the economic impact of the appreciation of the US dollar, the Fed's policy makers said in the minutes of their last meeting, released this week. But Donald Trump's focus on the strong dollar should persist.

In recent weeks, the US president has accused many countries of being currency manipulators and has threatened to impose sanctions on them. He has repeatedly invoked the strength of the dollar to pressure Fed Chairman Jay Powell to cut rates.

In May, the US Treasury added Ireland, Italy and Germany to its watch list of currency manipulators, placing them alongside China, Vietnam and Singapore – well that they are part of the euro area and have no direct national control over monetary policy.

For the first time in ten years, the tactics of competitive currency devaluation by beggars are making their comeback.

"We have the impression that we are considering a broader monetary policy war and that the currency problem is a symptom," said Geoff Yu, head of the UK investment office at UBS Wealth Management.

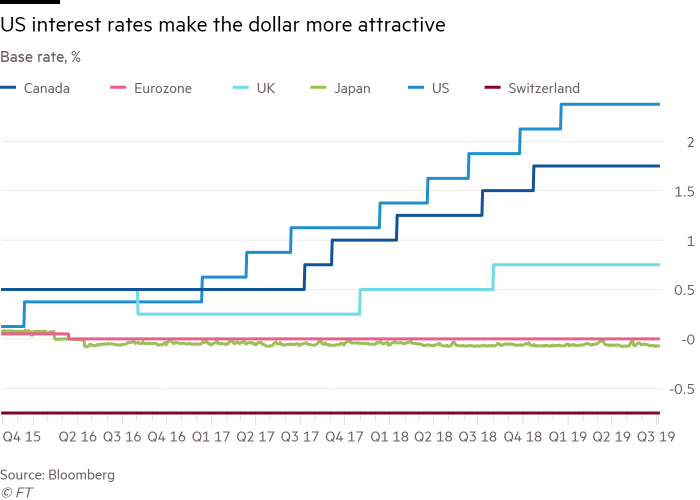

But this stems from a fundamental misunderstanding of what drives the currency markets, say analysts. The strong dollar is the result of the outperformance of the United States relative to other economies and the fact that its interest rate is higher than in most other developed countries, causing an influx of capital.

Alessio de Longis, senior portfolio manager at Oppenheimer Funds in New York, said US policymakers were able to raise rates while growth outside the US remained weak, leading to a stronger dollar.

"[The strong dollar] This is not an anomaly, "he said, adding that since Trump seized power, the threat of a currency war was threatening the world economy and" we are in a permanent state of negotiation of commercial agreements ".

Ed Al-Hussainy, senior currency and rate analyst at Columbia Threadneedle, said that the inclusion of Ireland and Italy in the Treasury's oversight report "was almost equivalent to a malpractice "and that the report contained" insane things "- even China obviously does not manipulate its currency anymore.

"Where rubber hits the ground, it's the renminbi [and] there is no indication that the Chinese central bank has intervened or manipulated its currency in such a way that it is. . . the language of the White House must be interpreted from a reelection [perspective]Said Mr. Al-Hussainy.

Mark Sobel, a US Treasury veteran and chairman of the US think tank OMFIF, said that even though there had been a case to qualify China as a currency manipulator a decade ago, this no longer was the case.

In the latest semi-annual report of the US Treasury, the Asian giant has checked only one of the three criteria: to have a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States, a "material" surplus of the current account and a "Persistent unilateral intervention". Foreign exchange markets – and, he said, this was not enough to deserve this label.

Maximillian Lin, emerging market strategist at NatWest Markets in Singapore, said Trump's claims against the renminbi could have remained outstanding until 2014, but data on Chinese currency holdings since then show that the People's Bank of China sold dollars, did not get them back.

"The Chinese [renminbi] is a victim of the trade war, not a weapon, "he said.

This is a remarkable turnaround compared to the situation of ten years ago – the last time that the manipulation of money has arisen in geopolitical circles.

Then, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, the US Federal Reserve's aggressive easing policy plunged emerging economies into turmoil.

At the time, US policymakers showed little sympathy for the fate of countries such as Brazil, continuing to take easing measures, regardless of the impact of a weak dollar on other economies, as rising exchange rates reduced their export earnings.

In 2010, the central banks of Brazil, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and China regularly intervened to stem the appreciation of their currencies. Brazilian Finance Minister Guido Mantega said the world was at the heart of an international monetary war.

On the contrary, the United States presents itself as the victim of the markets.

"It's a different type of monetary war when America thinks it's losing," said Kit Juckes, FX strategist at Société Générale.

In addition to the rate cuts and sanctions, Mr. Trump could apply other tactics.

Joseph Gagnon and Fred Bergsten, of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, suggested that the White House could consider retaliation through the money market itself: when a G20 country intervenes to devalue its currency, United States could deploy a compensatory intervention in the market.

For example, if Switzerland acted to weaken its currency by selling the franc, the Treasury could intervene to buy the same amount of the Swiss currency, canceling the intervention. "No one in the world has as much firepower as the US Treasury," said Gagnon.

George Saravelos, a Deutsche Bank strategist, said an intervention on the dollar "would not be unprecedented" and that previous administrations led by Carter, Bush and Clinton have all undertaken "frequent and significant interventions" .

"This has been an outmoded trend in recent decades," said Saravelos.

However, some analysts suspect that the Trump administration does not have a unified position.

Mr. Gagnon said that "the Treasury is looking for reasons to do nothing," he added, "if the White House will force them to act … is another matter."

Additional report by Hudson Lockett in Hong Kong

[ad_2]

Source link