[ad_1]

In July, an Uber driver we'll call Dave – his name was changed here to protect his identity – bought a ticket in a trendy neighborhood of a big American metropolis. It was rush hour and the price increase was due to increased demand, which meant that Dave would be paid almost double the normal rate.

Although the trip lasted only eight kilometers, it lasted more than half an hour, as his passengers had scheduled a stop at Taco Bell for dinner. Dave knew that he was sitting at the restaurant and was waiting for his rates to get a Doritos Cheesy Gordita Crunch or whatever it would cost him money. he earned only 21 cents a minute when the meter worked, compared with 60 cents a mile. With rising prices in effect, it would be far more lucrative to continue moving and recovering new rates than sitting in a parking lot.

But Dave, who got anonymized for fear of being neutralized by the grin giant for speaking to the press, had no choice but to d & # 39; expect. The passenger requested stopping via the app. Refusing to do so would have been contentious both with the client and with Uber. The exact number varies by city, but drivers must keep a high score to work on their platform. In addition, drivers are convinced that the Uber algorithm punishes them for canceling a trip.

In the end, the rider paid $ 65 for the trip for half an hour, according to a receipt viewed by Jalopnik. But Dave only won $ 15 (the rates were rounded to make the transaction anonymous).

Uber has kept the rest, which means that the company, valued at several billion dollars, has retained more than 75% of the tariff, more than triple the so-called "interest rate" average that she claims in the financial reports of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

If he had known in advance how much he would have been paid for the ride compared to what the rider paid, Dave said that he would never have accepted the fare.

"It's a robbery," Dave told Jalopnik by e-mail. "This business is out of control."

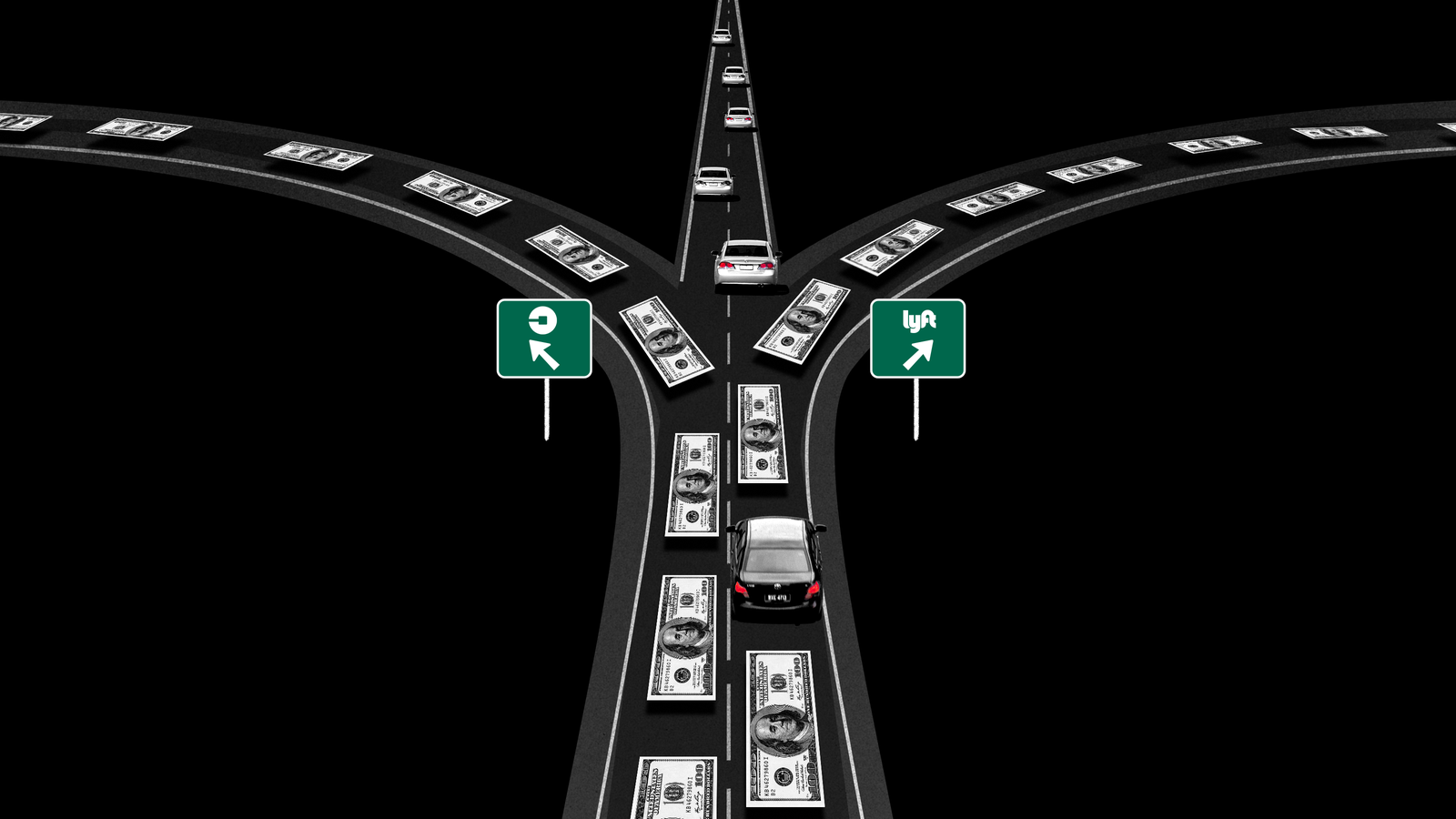

Dave is far from alone in his frustrations. Uber and Lyft have cut driver wages in recent years and now take a larger portion of each tariff, much more than the companies publish, based on data collected by Jalopnik. And the new Surge or Prime Time pricing structure, widely adopted by both companies, challenges a key legal argument put forward by both companies to classify drivers as independent contractors.

Jalopnik asked the drivers to send us receipts stating the total amount of the fees paid by the passenger for the trip, the share of that fare retained by Uber or Lyft and the earnings of the driver.

We think Uber and Lyft's new Surge tariffs are screwdrivers and screws. Help us prove it.

Uber changed the way his surge policy worked last year. Not for runners, but for pilots. Changes…

Read more

In total, we received 14,756 tariffs. These came from two sources: the Web form where drivers could submit their rates individually and by e-mail where some drivers sent us all their rates for a given period.

Jalopnik considered 35% of the turnover of all tariffs, against 38% for Lyft. These figures are broadly in line with a previous study by Lawrence Mishel of the Economic Policy Institute which concluded that Uber's participation rate was about one-third, or 33%.

Among the drivers who sent us an e-mail, the rates corresponding to all their rates for a given period, ranging from a few months to more than a year, Uber kept on average 29.6%. Lyft pocketed 34.5%.

These participation rates are respectively 10.6% and 8.5% higher than the figures published by Uber and Lyft.

In regulatory filings, Uber said its levy rate was declining from 21.7% in 2018 to 19% in the second quarter of 2019 (Uber refused to offer US-only figures for a more straightforward comparison). with Results of Jalopnik).

Business Insider previously reported that Lyft's participation rate for 2018 was 26.8%, although Lyft claimed not to publicly share their participation rates and refused to do so with Jalopnik.

When asked to comment, Uber and Lyft challenged Jalopnik's findings as erroneous and unrepresentative of their overall activities. But neither company accepted Jalopnik's request to provide statistically significant sets of anonymized tariffs for independent verification, maintaining the long-standing data confidentiality scheme.

The results "corroborate the argument that their business model is based on exploitation by large-scale work"

Trips like the $ 65 Taco Bell just highlight inequities between multi-billion dollar businesses and drivers who earn wages at or below the minimum wage. Asked about this tariff, an Uber spokesman acknowledged: "The new wave of crisis has solved all the problems, but it also presents difficulties: the most important of them is the fact that drivers can earn comparatively less. longer trips, even if they win more often. "

The spokesperson added: "In order to better serve drivers, we often increase the increase payments for longer journeys with additional amounts that vary according to the duration of the trip. Drivers are able to see this extra amount on the receipt of their trip once the trip is over. Dave did not receive any such increase.

Travels like Dave's also reveal inconsistencies in the very logic in which these societies evolve. Drivers like Dave are technically independent contractors, but they have no control over many aspects of their working lives, including the price of their own services.

"It's really fascinating and disturbing," said Sandeep Vaheesan, legal director of the Open Markets Institute, a non-profit organization that studies corporate concentration and monopoly power when informed of the findings of Jalopnik. Vaheesan went on to say that the results "support the argument that their business model is based on exploitation through large-scale work".

"As far as I know, it's the most convincing data we have at the individual driver level on Uber's share of each driver's gross earnings," said Marshall Steinbaum, an economist at University of Utah, which studies labor markets. "And in this respect, it makes a lot of progress in understanding the functioning of these labor markets."

He added that "if their [Uber and Lyft’s] The answer is that it is not representative of all the drivers, but many others who have tried to verify their claims and found them insufficient. "

The Jalopnik dataset is certainly not perfect. The sample of 14,756 notes represents a tiny fraction of the millions of trips made each day by Uber and Lyft in the United States alone; it would be impossible for an independent researcher to get hold of an adequate data set without the cooperation of Uber and Lyft (or, in theory, more harmful methods such as hacking or data breaches).

And there is almost certainly a certain selection bias in the Jalopnik data acquired via the Web form for drivers who are unhappy with them and who would therefore be more likely to take the time to submit their fare. In the same vein, the rates that Jalopnik received via the web form came disproportionately from outside the major Uber and Lyft metropolitan markets and during peak periods, which indicates a possible selection bias in our results.

"While 8,926 tariffs represent a significant increase in The 175 that you had before, "said an Uber spokesman," this is still not a statistically representative sample, since Uber makes about 15 million trips a day in the world. "

But there is also reason to believe that our findings are more representative of the individual driver experience than Uber and Lyft would like to admit. Even the full price records received by Jalopnik showed a higher catch rate than previously. And Steinbaum observed that these factors may have a selection bias in the other direction.

By keeping records diligently, "these are probably the most savvy drivers and therefore those that businesses are least able to deceive, so to speak, so that you could get an underestimation of their spinoffs."

Lyft also challenged him. A spokesman told Jalopnik: "Even though the survey looked at each route for a handful of drivers, the sample of pilots had to reflect accurately [sic] a representative sample of all Lyft pilots, not just a specific subset (that is, the sample size was sufficiently diverse to indicate that this represents the average experience of the Lyft pilots in all areas). "

In regulatory filings, trials and their terms of service, Uber and Lyft claim to simply be facilitators between the driver and the driver, not a transportation service. They claim that their real customers are drivers. And drivers pay Uber and Lyft a share of their earnings to put them in contact with their customers, runners. This echoes a common thread in Silicon Valley: they are just technology companies and should not be subject to the regulation of the industries they disrupt.

Uber's twisted logic means it's not a strike. It's a boycott

Today, many Uber and Lyft drivers in major cities across the country are on strike to protest …

Read more

But in recent years, in an effort to limit their multi-billion dollar losses, the two companies have dissociated the price that passengers pay from what drivers earn, moving away from a commission based on a strict percentage.

Using the so-called Upfront Pricing, first introduced in 2016, Uber tells riders the exact amount they will pay before the start of the trip based on the prediction of their own algorithm (as often, Lyft has introduced the same policy soon after Uber). It then compensates the drivers based on the actual time and distance of the trip.

According to both companies, the modification of the Upfront pricing was made in response to customer and driver comments. the riders did not want to be surprised by a higher bill, and the drivers wanted to be paid for the work actually done.

This common sense policy has potentially profound legal implications. In practice, Upfront Pricing dissociates the rider's payment from the driver's earnings; a price is set before the trip based on an estimate, the other after the end of the trip depending on the reality.

This change is more evident with the way Uber and Lyft are now dealing with periods of high demand. Along with the move to Upfront pricing, both companies have also changed the way they operate their high-demand pricing model, often called Surge or Prime Time (Lyft has since changed the name of the brand to Personal Power Zones for drivers).

Instead that drivers receive a multiplier on their earnings, as Dave did for the Taco Bell race, most now receive a lump sum bonus, usually only representing a few dollars per ride. Uber and Lyft will sometimes give drivers an extra boost if the surge is particularly strong or the race is particularly long, but there seems to be little rhyme or reason for this to happen. Meanwhile, runners always pay the multiplier, which means that runners often pay a lot more than drivers earn on those trips.

"It shows that this is a company that charges consumers and then makes decisions with that money, including how to pay for a workforce."

A spokesman for Uber explained this dynamic to Jalopnik in these terms: "While the increase experienced by drivers and drivers is linked to real-time imbalances between supply and demand, the benefits of driver and the earnings they earn on a given trip is not always the same. This is partly due to the fact that the increase in the number of new drivers is based on their location and not on that of the driver. This means that a driver can receive a surge during a trip, even if the runner does not pay extra. "

Similarly, a spokesman for Lyft said, "Lyft continues to pass the Prime Time pilot to drivers, via PPZ, at the same rate overall. There are differences in the level of travel but these differences are reduced in both directions ", in that drivers sometimes earn a generally higher or lower percentage of the fare.

In other words, Uber and Lyft stated that they took all the excessive fees that passengers pay and distribute the product among all drivers in the area, whether their passenger pays a special fare or not (both companies deny any simply that they pocket the difference).

This, according to Sanjuka Paul, a law professor at Wayne State University, who has written extensively on the stimulus industry, is a new trait in the debate on independent entrepreneurs because it does not match the arguments put forward by companies that only facilitate interactions. between two independent players in a market.

"The economic reality is that they, Uber and Lyft, take the tariff from the consumer and then make a capital decision, which in this case does not seem to be a very bad decision – in fact, a decision all makes sense, "he said. "But it shows that this is a business that charges consumers and then makes decisions with that money, including how to pay for a workforce."

Or, as Steinbaum says, "what they do is exactly what employers do with their workers."

In addition, businesses can and have changed the basic time / distance rates that drivers earn at all times. And there have been a lot of wage cuts.

Uber and Lyft deny that driver earnings have declined. "Although not all drivers have the same experience," Uber spokesman Jalopnik wrote, "this is not what we see when we look at trends in average hourly earnings of drivers over time. of the last two years, which have increased.

A spokesman for Lyft told Jalopnik that the number of drivers on their platform is increasing and that their revenues have increased over the past two years. The company claims that drivers earn "more than $ 30 USD per hour nationally", although this figure represents only the time elapsed between the time a driver accepts a request for transportation and the time when the driver passenger is deposited, not including expenses.

Some drivers were not even aware of the magnitude of changes in company fares for both high-demand and all-round trips until they compiled their records to be sent. in Jalopnik. A driver, who has been working for Uber in Texas for three years, sent us nearly 500 airline tickets.

"It's a bit depressing to know that Uber occupied 20% when I started and now gets 31% on average, with rates going up to 50%," he said. declared.

A former full-time driver from Iowa said that prior to the wage cuts that had finally reduced his per-mile rate by more than half, he estimated that about 30% of the rates that I & # 39; He had obtained corresponded, after the reduction of Uber and Lyft, to a waste of time. . After these changes, starting in 2018, he says that the number of unwanted fares is now closer to 70 or 80%, which is why he stopped driving full time.

(It is difficult to compare rates of care with the taxi industry significantly, when drivers have to pay a fixed fee such as shipping, taxi hire and / or reimbursement of In fact, many taxi drivers turned to the chairlift because the percentage commissions, as well as the huge registration fees offered by Uber and Lyft, seemed to be a better offer. )

Drivers' frustration at Uber and Lyft's wage cuts and rising participation rates adds to other inequalities in the hail industry.

Uber and Lyft argue that drivers are not employees, but independent contractors, since they are allowed to set their own schedules. Both companies rely heavily on this arrangement in ads and promotions to recruit drivers, using phrases such as "be your own boss" to describe the arrangement.

But the reality is much more complicated. In fact, drivers do not have the power to make many of the decisions generally associated with self-employment. The most important of these is the ability to set prices – or even negotiate – for the services provided.

In driving contracts, both companies claim that drivers accept their new fares simply by continuing to drive for the company. In other words, the only recourse available to drivers in the face of a reduction in pay is to leave their job; a familiar arrangement for any employee, but not for anyone who is his "own boss" and therefore would not have any income determined by another company's ever-changing ruleset.

"It's really crazy how companies have carte blanche to deprive us of our rights by contract," Vaheesan wrote in a follow-up email after Jalopnik showed him the language of the contract. "The courts and Congress have basically accepted this scheme as normal."

In addition, drivers have the option of refusing or canceling trips, but drivers are convinced that if they do so too often, they risk being "idle" without being asked for a certain amount of time. . Frequently documented phenomenon in driver forums and blogs.

Drivers do not have the power to make many of the decisions that usually result from self-employment. The most important of these is the ability to set prices – or even negotiate – for the services provided.

Both companies deny punishing drivers in any way for the downtrodden routes, but Lyft acknowledged that some incentives are only available to drivers with a high commuting rate.

In another attempt to increase revenue, Uber deploys Comfort mode, which offers riders extra equipment such as a car with more legroom, the ability to set the desired temperature or ask the driver to remain silent for an extra charge (drivers for Comfort journeys enjoy a few extra cents added to their mileage and mileage). rate of time).

Uber said that it was just a request to the driver and not a requirement, but that drivers would probably not be satisfied if a driver refused to follow through on a request. request for which they had paid a supplement. If a driver does not follow the instructions, it is likely that he will get at least a lower grade.

Taken together, rather than being their own boss, drivers often feel governed by algorithms, as Alex Rosenblat writes in his book, which is the subject of a deep report. . Uberland: How algorithms rewrite work rules. This algorithmic "boss", which sets pay rates opaque and governs work rules through DIY arrangements, eliminates all liability, but forces drivers to guess what the algorithm wants . In his book, Rosenblat wrote:

An algorithmic manager promulgates his rules, penalizes drivers who act in a manner different from that suggested by Uber and encourages them to work in particular places at particular times … When I ask drivers if they are their own boss, they usually pause and notice that it is somehow true, and that they set their own schedule. But an employer of application provides a type of experience that differs from human interactions and it can be difficult to identify the fault lines of autonomy and control within its automated system .

In an interview for this story, Rosenblat, who spoke to hundreds of drivers researching his book, added that drivers had different reactions on outings where they thought they were not entitled to a fair cut.

"Some drivers were furious and would say that if I'm an independent contractor, you should give me the information I need to make an informed choice," said Rosenblat. "But other drivers tend to think that taking a bad flight is a bit like karma.If you only take one passenger a few blocks from this trip, you could be compensated for a better ride over." later. "

Rosenblat added that the theory of karmic realignment is a direct result of the lack of transparency of the giants of the tour-hail. She called it "magical thinking" [drivers] If Uber and Lyft gave them the means to make informed decisions, or to better understand how they could be treated, rewarded and penalized for their work, with valuable or less useful dispatches.

A veteran veteran driver from New Orleans told Jalopnik that she somewhat subscribed to the theory of karmic realignment on catch rates, although recent cuts have slightly changed her attitude. It saw its revenues fall by about 20% this year due to a number of factors, including an increase in the number of drivers, as companies allow older vehicles than in previous years. As a result, she is considering an employment change, even though an occasional health problem makes flexible hilarious driving hours particularly appealing.

Even though she prefers to lead to her previous jobs in the service sector, she has come to believe that Uber and Lyft's participation rates should be capped, perhaps at 25 or 30 percent, and that they are not going to go down. it would support a driver recruitment campaign for the more sustainable profession.

But for now, she always avoids looking at individual rates. "It bothers me," she says, "and I can not do anything about it."

[ad_2]

Source link