[ad_1]

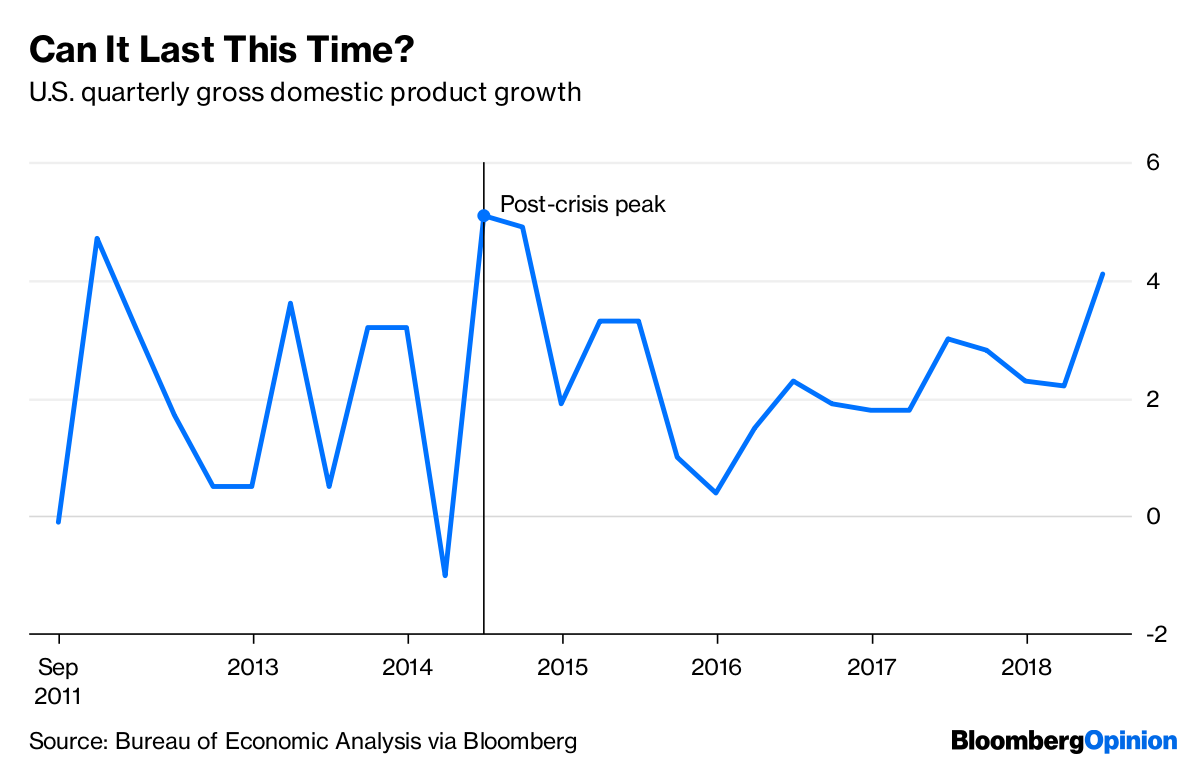

The strong report on Friday's second-quarter gross domestic product raises the question of whether it can be sustained as it was not the last time that GDP growth was so robust four years ago .

Things are going badly for the current economy – a rate of federal funds firmly anchored at zero and an economy that is still operating well below its potential, which suggests a growth margin without the fact that the economy is in a good position. inflation becomes worrying. Yet, an unexpected shock came in the form of the collapse of energy prices that slows growth over the next two years.

The good news of 2018 is that it's hard to see a shock of demand that could derail things. energy did four years ago. But the bad news is that with the economy now operating above its potential, we will need some good surprises if this rate of growth is to be maintained.

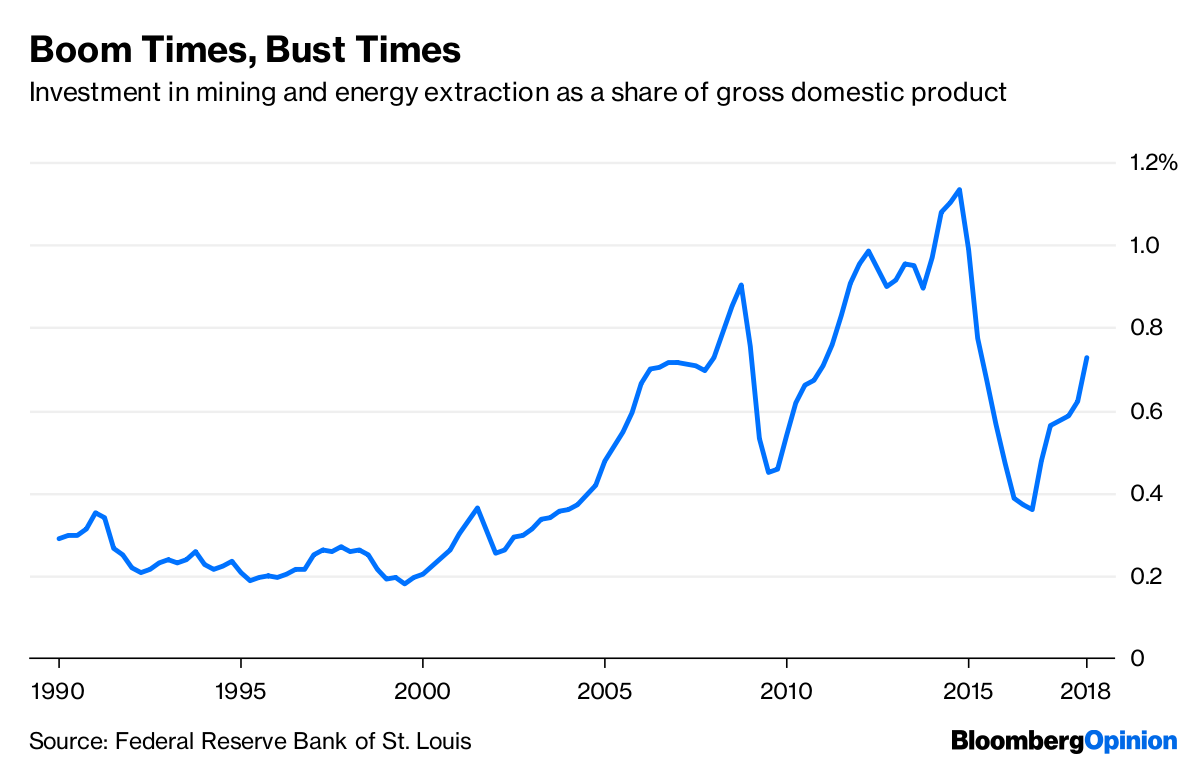

The surge in economic growth in the second and third quarters of 2014 was largely due to a boom in energy investment. In the 1990s, the share of GDP attributable to fixed investments in mineral exploration, wells and wells was 0.2%. This share began to increase in the mid-2000s as higher oil prices prompted companies to invest more in energy production. This really took off after the financial crisis as technology improved, new sources of supply were identified and the price of oil remained high. The same share of GDP attributable to mining investment peaked at 1.1% in the fourth quarter of 2014.

Boom Times, Bust Times

Investments in mining and energy extraction as a share of gross domestic product [19659007] Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

This may seem relatively modest in the context of the large US economy. Of course, this is not just the direct impact of this investment that matters, but the multiplier effects. Industrial companies had to build equipment to support the industry. Trucking and railroads posted higher revenues as machinery and raw materials had to be shipped. In the West Texas shale zone, workers are better paid, which means they can spend more for consumption. Tax revenues have increased. Companies and countries around the world have benefited.

But the bust reversed all that and then some. Indeed, in times of recession, investments fall faster than they progress in the boom; it took only six quarters for energy investment as a percentage of GDP to erase five years of growth. The contagion effects have started the supply chain for the industry and the global economy, while the dollar has jumped, emerging economies have struggled and credit spreads for the whole of the economy have widened, investors fearing the extent of the damage. In the fourth quarter of 2015, GDP growth was down from 5.1% in the second quarter of the previous year to 0.4%.

Can the United States last? Quarterly Gross Domestic Product Growth

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Bloomberg

The good news of 2018 is that the energy crisis has already occurred, which should not undermine the economy today. ; hui. Housing is still an industry that people think of when they talk about the risk of economic downturn. Yet while land, labor, raw materials and interest rates have all increased, housing demand remains robust, with millennials entering their family formation years and the low supply in the market. Disorder seems to be the worst case scenario for housing for the moment

The challenge for the economy is how much more remains to be done to grow without accelerating inflation. This remains an unknown. Essentially, there are three frameworks for the state of the economy right now, and everyone is saying things that are to some extent in conflict.

The first focuses on the unemployment rate and demographics. The unemployment rate is low and the prospects for expansion of the workforce due to population growth are minimal. As a result, economic growth that puts downward pressure on the unemployment rate could lead to a faster rise in inflation. Keep in mind that the unemployment rate, now at 4%, is lower than the Federal Reserve's estimate of full employment.

A second model of participation in the labor market presents a very different point. Over the last 20 years, wage growth has been more closely correlated with the employment-to-population ratio than the unemployment rate. As the participation of the very active working age workforce has not yet reached its peaks before the crisis, the employment-to-population ratio can still increase before wage and salary increases Inflation does not get out of hand. This suggests that the economy should still have some room for growth.

A third model basically says that inflation has not been a problem for so long that we should not worry about it until it is there. It is true that inflation in the United States and around the world has been below the central bankers' target since at least the late 1990s. It is also true that for two consecutive economic cycles, the Fed has monetary policy too hard, leading to recessions. For these reasons, we would better wait until we are absolutely sure that inflation is a problem rather than relying too heavily on models that have proved to be short-term in the last generation.

The prospects for sustainability of strong economic growth boil down to which model or models you believe. Between the stimulus of the tax bill, the absence of obvious signs of overinvestment in the economy and the millennial demographics, it is possible that demand growth may remain strong for some time. It is simply a question of how long it will take for inflationary bottlenecks to occur and if the Fed decides to raise its rates sufficiently to end the cycle.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board

To contact the author of this story:

Conor Sen at [email protected] [19659022] To contact the person in charge of this item:

James Greiff [19659022] at [email protected]

Source link