[ad_1]

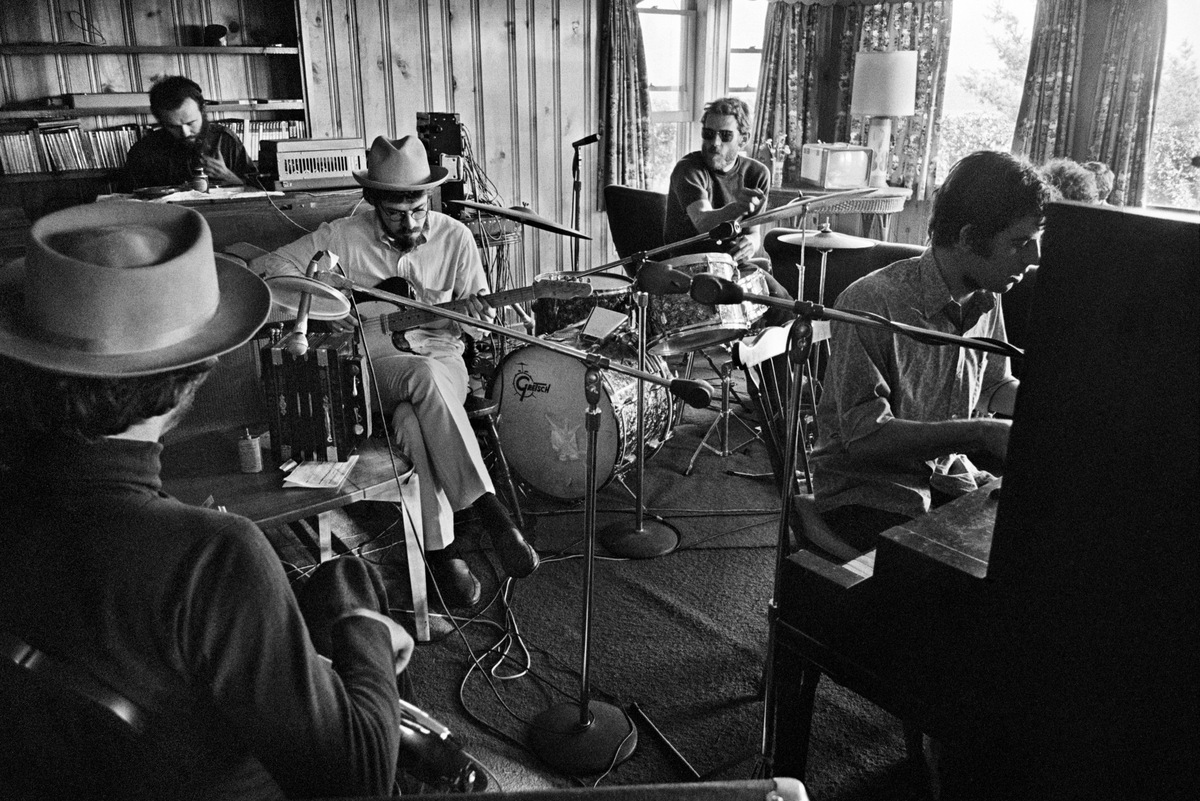

After much research, we found the perfect place right outside their window. Where did he find us? Levon and Rick's yard. Woodstock, New York, 1968

The first suspicion of otherness comes from voices.

They are five in number, each shredded and tired in his own way, each contributing to "Tears of Rage" according to his own schedule, when he is stirred by a spirit. Resembling less a polite choir than a wandering militia, they seem out of place, out of time. The voices have no discernible connection at the time the record arrived in 1968. They might as well sell elixirs at the back of a horse-drawn platform, moving to the rhythm slow and deliberate rural America of the days before [farm-to-table] shallots.

The music of group was released on July 1, 1968.

hiding legend

rocking legend

The harmonies of Richard Manuel, Robbie Robertson, Rick Danko, Garth Hudson and Levon Helm draw attention to "Tears of Rage" – and really Music From Big Pi nk – because they are so voluntarily and completely alien. Inside this mass of strident, the songs of effort are allusions of church bells and orations of tombs and tablecloths, echoes of times where everyone sang and sang together, no matter how creaky. Their evocations offer a temporary invitation: Come in and go around. But be careful because it is not a record. It's a world

Music From Big Pink has been with us for 50 years now, and although its DNA has been indefinitely crumpled and analyzed, it retains somehow its outer aura, its ability to surprise, his unusual gift for bending and twisting chronological time.

Big Pink was unexpected on arrival and remains so again. It responds to the accelerated gallop of progress towards 1968 with murderous ballads and allegorical teachings of the hymns, accompanied by a pumping organ and piping brass from a community group. It's an attic curio, certainly, but one that has activated ten distinct strains of nostalgia, while opening avenues the size of a highway to future exploration. (The vaguely defined territory "Americana" being one among others …) He taught essential lessons on the importance of a sound framework for a song, and on how to let it breathe a song so that words, even cryptic ones, flow

At the heart of the album, the approach to collaboration that prevailed inside the Big Pink House in West Saugerties, NY, in the basement where, after accompanying Bob Dylan on his first electric tour in 1966, The Band and the Bard spent months working on songs and exploring sounds. According to legend, when producer John Simon asked what was the sound that The Band was pursuing, Robbie Robertson replied that they wanted the music to sound "Like in the basement".

Robbie in the center, Richard at the piano, rehearses at Richard and Garth's house on Spencer Road. Woodstock, New York, 1968

They ended up capturing the disc in New York and Los Angeles studios – total recording time: less than two weeks. But drop anywhere on the set of Dylan The Complete Basement Tapes that came out in 2014, and you're experiencing the aura of this basement space, and l & # 39; Fertile, almost viral creative energy that has occurred there. The band may have been hired as an accompanist for Dylan, but they quickly became accomplices – and by helping Dylan develop this material, the five multi-instrumentalists discovered (and then refined) the signature features of their own company. . 19659004] Fighting with the mythical songs of Dylan had to help these musicians to forge that rustic identity that became the group's calling card. They learned to sing together in a wonderfully irreverent and ad hoc way. Then they adapted this vocal approach to the songs each of them wrote, songs that aligned and stretched the already expansive sound of the collective. No matter who was singing, whether the melody was a "Chest Fever" or a "In a Station" meditation, The Band always managed to stay completely out of the way, in his own airspace. ] Many rock veterans view Big Pink as a sacred text. Eric Clapton, who would have been haunted by this, confessed to having listened every day. Roger Waters placed it just behind the Beatles Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band is the most influential record in the history of rock. "Sonically, the way the disc is built, I think Music From Big Pink is fundamental to everything that happened after."

In the ramifications of scholarships devoted to this disc, it is possible to find a zillion of the specific elements within the music that reinforce the broad statement of Waters. Some might be technical considerations, the colorful chords melting the band sing. Some might be spiritual, unseenly linked to the vanished values of Sunday School. All share at least one thing: the deep element of the unexpected. Think about that moment. No one, at the time of the Chicago Democratic National Convention, who witnessed the turmoil of 1968, expected a balm like "The Weight" or, anyway, any of the songs of Music From Big Pink . Rock became more and more psychedelic; something small and fragile and of a human scale was not in the realm of possibility. He came out of nowhere, that basement sound. He snuck out and took up his place without getting in the air. And it haunts us again.

Source link