[ad_1]

More than half of the world's population of vertebrates, from fish to birds to mammals, has been exterminated in the past four decades, according to a new report from the World Wildlife Fund.

According to the 2018 edition of the Living Planet Report released Monday, between 1970 and 2014, the decline was on average 60% among 16,700 populations of wildlife around the world.

"We have lost an average of almost two-thirds of our wildlife species," said James Snider, WWF-Canada's Vice President of Science, Research and Innovation.

"The magnitude of this phenomenon should open our eyes … We are really about to see species disappear, it's true in Canada and abroad."

The situation is particularly serious in:

-

The "Neotropical Kingdom" includes Central America, South America and the Caribbean, where wild animal populations have declined by 89%.

-

Freshwater ecosystems, which abound in Canada, where populations have decreased by 83% worldwide.

Declining species include Canadian species such as barren ground caribou and North Atlantic right whales, as well as many migratory species such as songbirds and monarchs breeding in Canada.

Vertebrate populations around the world have decreased by an average of 60%, according to the World Wildlife Fund's Living Planet Report 2018. Barren-ground caribou are among the species that have experienced dramatic declines in Canada. (WWF-Canada)

According to the WWF, the main factors of decline are habitat loss and overexploitation, but climate change is a growing threat.

In Canada, habitat fragmentation due to human-built structures such as roads, pollution and invasive species is wreaking havoc, Snider said.

The Living Planet report, published every two years to monitor global biodiversity, is based on the Living Planet Index, published every two years since 1998 in collaboration with the Zoological Society of London and based on international population databases. Wild species. The two previous reports, in 2014 and 2016, revealed that wildlife populations have decreased by 50% and 58%, respectively, since 1970.

Snider said the results of the new report show a trend in the wrong direction, and "there is a real urgency" to take action to protect wildlife.

In Canada, he says, political leaders are committed to doing so through the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity, protecting 10% of marine areas and 17% of its land, although we do not have the right to do so. have not yet achieved these goals.

"We are far behind," he added.

Protecting forests, wetlands and coastal areas to preserve wildlife may also have a secondary benefit, as these types of ecosystems also store carbon and prevent it from being released into the environment. 39 atmosphere, said Snider.

"There can be a real benefit in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. "

The publication of the report took place just hours after two new studies in PNAS highlighting the results.

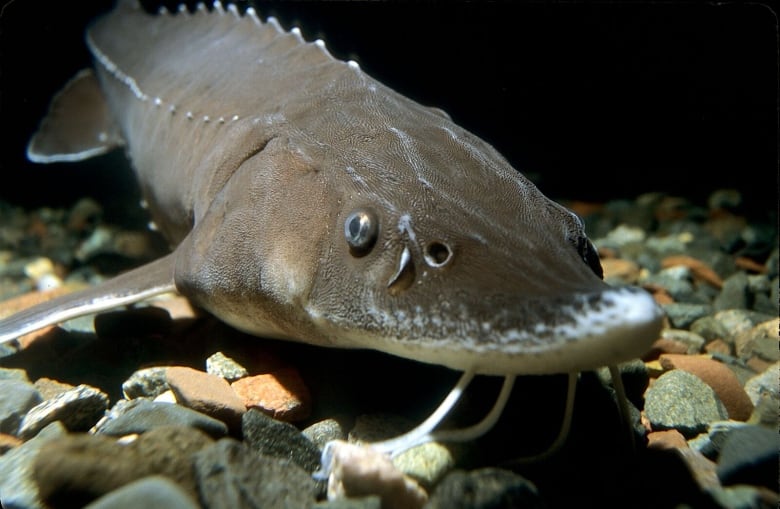

A lake sturgeon swims in the Great Lakes. According to the WWF, freshwater ecosystems have experienced the largest decline in wildlife populations. (Engbretson underwater photography)

& # 39; Escalator to extinction & # 39;

One of them, led by S. Blair Hedges of the Center for Biodiversity of Temple University in the United States, revealed that less than 1% of Haiti 's primary forest remained and that many endemic species, including amphibians and reptiles, had been exterminated. with the trees.

The other, led by Benjamin Freeman, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of British Columbia's Biodiversity Research Center, says climate change is an "extinction factor" for birds tropical species living at high altitude.

The study investigated bird species living on top of a mountain in a remote region of Peru, where the man did not cause any loss of life. habitat, and compared the results to those of a survey conducted in 1985.

The red-crowned warbler also lives in the high altitudes of Peru. Eight other species discovered in a previous survey in 1985 could not be found in the most recent survey. (Graham Montgomery (University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT)

"Nearly all high altitude birds are declining dramatically in abundance, "said Freeman.Eight species from the previous survey were untraceable, and Freeman said that for five of them," we are confident that ". they left ".

The study confirms predictions that climate change will result in a decline in the population in such habitats.

"It's a wake-up call," Freeman added.

While his study focused on biodiversity in a small area, he said that global measurements such as the Living Planet Index are useful because they show more clearly the loss of biodiversity than the measure of extinctions.

"To draw attention to the decline of abundance is an important thing," he said. "It's really the main way humans impact plants and animals, we're changing the landscape, so they're much smaller."