[ad_1]

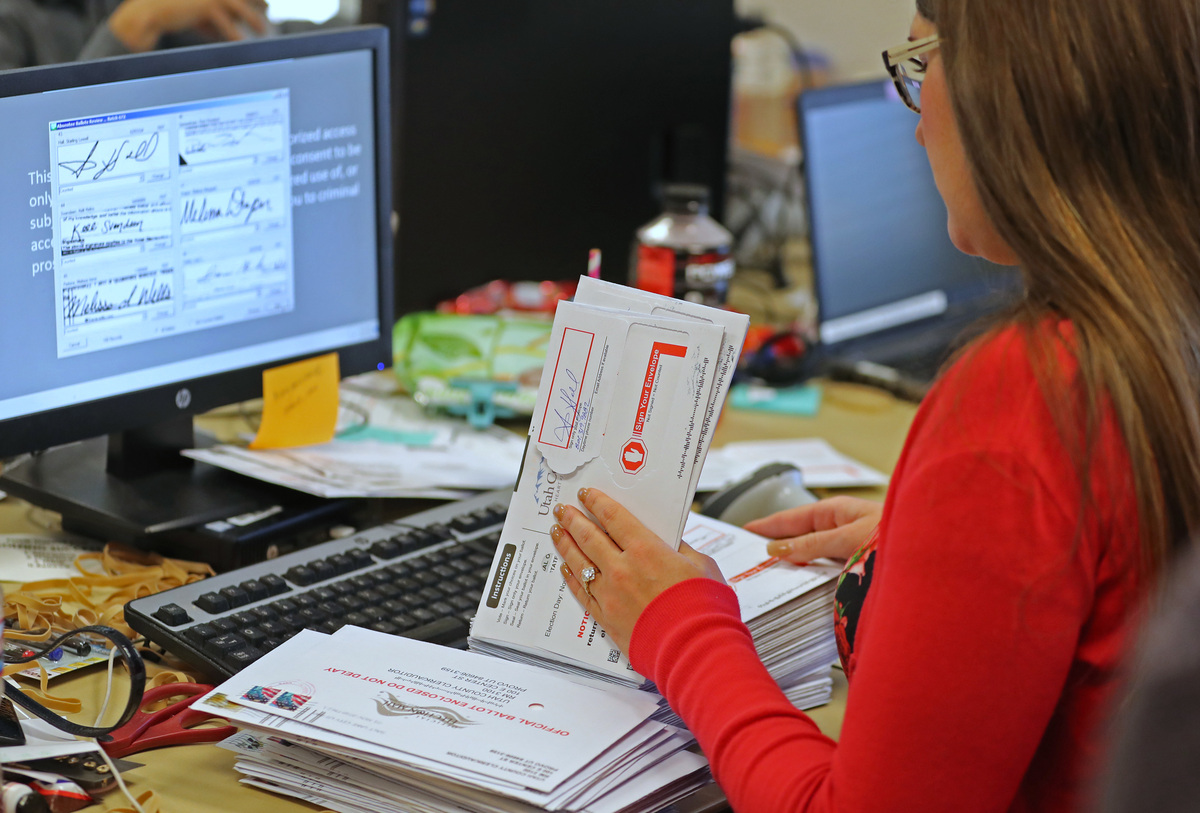

A Utah County poll officer verifies the signatures on the postal ballots for the mid-term elections on November 6th.

George Frey / Getty Images

hide the legend

activate the legend

George Frey / Getty Images

A Utah County poll officer verifies the signatures on the postal ballots for the mid-term elections on November 6th.

George Frey / Getty Images

Before, it was a sign, a credit card receipt or even a love letter. But the art of signing has become less important and less practiced, which means less certainty for election officials from several states that still count the votes of the mid-term elections of November 6th.

These officials try to verify that the required signatures on the postal, provisional, correspondence and military ballots correspond to the signatures of the voters in the records of the election office.

But the signatures change over time – a problem especially for young voters, says Daniel Smith, professor and director of the department of political science at the University of Florida.

"Say you're a 16-year-old civilly citizen and you're pre-registering to vote in Florida, which you're allowed to do," Smith told NPR. "You may have a signature that has the heart on it's your name as a 16-year-old man, but you come to the University of Florida to become a Gator." sophisticated, and your signature now looks very different. "

Smith, author of a study on the subject for the American Civil Liberties Union of Florida, says that it is the signature that the elector has created at age 16 that is going to be signing folder.

This causes problems for the younger ones, "whose signatures are not fixed in a digital world, where you sign your name with your finger on an iPad," says Smith. This could deprive young voters of their rights, which he says is "somewhat incompatible with the right to vote".

If the signature of the minutes does not correspond to that of the last ballot, this vote could be reported and potentially not counted.

Smith says his study found that younger voters were four times more likely than their electors over 65 to have their ballot papers rejected.

Another problem, he says, is that many election officials are not well trained to compare signatures.

"You can not just match a signature with another signature and be certain that it's the same person who wrote them both," Smith said. "You must have different signatures," he says, because the signatures vary "depending on the condition in which they write the signature, the type of pen they use, that they do it at the same time." 39, inside or outside. "

In Colorado, where every voter receives a postal ballot, officials are well trained to read the signatures. In Denver, former Chief Electoral Officer Amber McReynolds said the county electoral council had hired a writing expert to develop training materials.

"He was involved in every election cycle and trained the judges on what to look for, how to approach the signature check – all that," said McReynolds, now executive director of the National Vote at Home Institute.

According to McReynolds, most of Colorado's larger counties use signature software that is more consistent than their eyes. The biggest problem, she says, is whether there's enough time left for voters whose signatures do not match, correct the differences before the deadline for counting votes.

Most states with good procedures "allow this to happen generally eight to ten days after the elections," she said, "so that voters can return the affidavit and other items required for their election." To make sure their vote counts. "

In the state of Washington For example, counties have three weeks to count ballots, provided they are posted before polling day. in California, officials have a month to complete their work.

Source link