[ad_1]

A daring team of scientists has explored the mystery of the cube-shaped wombat poop, uncovering the physiological processes involved in this unique digestive trick.

The wombats are a little obsessed with their own shit.

These Australian marsupials can deposit four to eight pieces of excrement, each measuring about 2 centimeters in diameter, during a single excretion session. More impressive, however, is the cubic form of their poo.

During the course one evening, these nocturnal creatures can produce 80 to 100 cubes of poo, which they collect and place strategically around their domain. This scatological behavior serves at least two purposes: poop is used to mark the wombat's territory and, so to speak, attract friends (do not judge). Strangely geometric dimensions improve stacking and prevent shit from rolling. The cubic poop of wombats is therefore an evolutionary adaptation, and not simply an irrelevant side effect of biology.

The way the wombat's body is able to create this cubic poop is however not well understood (I know what you think, and no, the wombats do not have squared butt holes, but they are well tried). Patricia Yang, a postdoctoral fellow in mechanical engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology, recently conducted an investigation. Yang is an expert in hydrodynamics of body fluids, such as digested food, blood and urine. The results of his research should be presented at the 71st Annual Meeting of the Fluid Dynamics Division of the American Physical Society in Atlanta.

"The first thing that has led me to this is that I have never seen anything so strange in biology," Yang said in a statement. "It was a mystery. I did not even think it was true at first. I googled it and I saw a lot on the cube – shaped wombat poop, but I was skeptical.

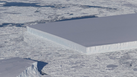

This geometrically strange iceberg makes us panic

Well, it's something you do not see every day: an iceberg of such an incredibly geometric shape that you …

Read more

Indeed, cubes are rare in the biological world. We panic even when it happens in the geological world. Yang's investigation aimed to understand how wombats – the only animal known to drop cubic droppings – were able to achieve digestive damage, and to determine which aspects of their physiology were responsible for it.

Yang and his colleagues performed autopsies on wombats that had to be euthanized as a result of road accidents. The researchers focused on the animal's food system, also known as the digestive tract.

Yang and his colleagues have noticed that, towards the final 8% of a long trip to a dike in the digestive tract (it takes up to 2.5 weeks for the food consumed to go down into the digestive tract of the wombat), the consistency of shit changed to solid. At this point, the poop consisted of small, discrete cubes each about 2 centimeters wide, but that's where the magic works, that is to say, the transition from a form of tubular poo to a form like a cube.

"Previous studies have hypothesized that cubic stools form at the very beginning of the small intestine," Yang told Gizmodo. "Our study shows that this is not the case. The feces become cubic at the end of the large intestine. "

The transformation, says Yang, is due to the variable elastic properties of the intestinal wall of the wombat. By emptying the intestine and inflating it with a long balloon, Yang's team found that the elastic stress on the poop varied from 20% at the corners of the cube to 75% at the edges. As this research shows, the walls of the intestines literally shape the poop through the strategic placement of pressure.

Interestingly, this study has implications outside of biology.

"Molding and cutting are the current technologies for making cubes," Yang told Gizmodo. "But the wombats have the third way. They form cubic feces by the properties of the intestines. "

Indeed, this digestion technique, according to the authors, could be applied to mechanical engineering. The discovery could also be applied to medicine, such as the treatment of gastrointestinal problems. According to Yang, his group's findings could improve our understanding of soft tissue transport in the body and how the digestive tract moves.

"We can learn from wombats and hopefully apply this new method to our manufacturing process," Yang said. "We can understand how to move this material very efficiently."

Ah, the areas of biomimicry seem to know no limit. But who would have thought we could be inspired to build advanced systems based on the quirk that is the poop of wombat? Not me, my friends, not me

[Bulletin of the American Physical Society]Source link