[ad_1]

EToday, it seems increasingly unlikely that we are meeting the World Health Organization's goals of physical activity and reducing the "obesity epidemic". research published in Nature Communications, we can begin to blame now. If all else fails, we'll just pin it on dad's genes.

Led by a team of scientists from Germany, Denmark, and Austria, the study shows how each parent's genes contribute to how fat cells grow in the body. . The fat can differentiate into two types: white tissues, which store energy and are associated with obesity and metabolic diseases; and brown adipose tissue, which actually burns energy and produces body heat.

Dad's white fat

Everyone has a little bit of both types of fat. To determine which genes are responsible for both types, the authors of the new study examined mice with a high proportion of white or brown fat. They found that the genes controlling fat differentiation belong to a small percentage of "monalelle" genes. Most genes are expressed equally from two copies, or "alleles," inherited from each parent. In some cases, both parents provide the same allele of a particular gene, while in other cases, parents provide different alleles, resulting in a variety of physical characteristics, such as eye color and the blood group.

But the monoallelic genes are different. Although you have two copies of the gene – one from your mother and one from your father – only a copy is actually expressed.

The co-author of the study, Jan-Wilhelm Kornfeld, Ph.D., from the University of Southern Denmark, tells reverse As far as genes linked to white fat are concerned, dad's inherited alleles are more likely to be expressed:

"Some of these paternal genes promote growth, and it is in our father's best interest to make us strong and provide us with sufficient energy resources to promote the development of white fats," he says.

Mom's genes to the rescue

In a fine example of parental cooperation, Kornfeld and his co-authors found that with a little help from the mother's genes, these effects can be mediated or even reversed. A gene called H19 that has the power to mitigate the effect of dna genes on adipose tissue. People tend to express the copy of H19 that comes from mom's side:

"Our results show that H19 acts as a so-called gatekeeper for a handful of genes that normally suppress the development of brown fat," says Kornfield.

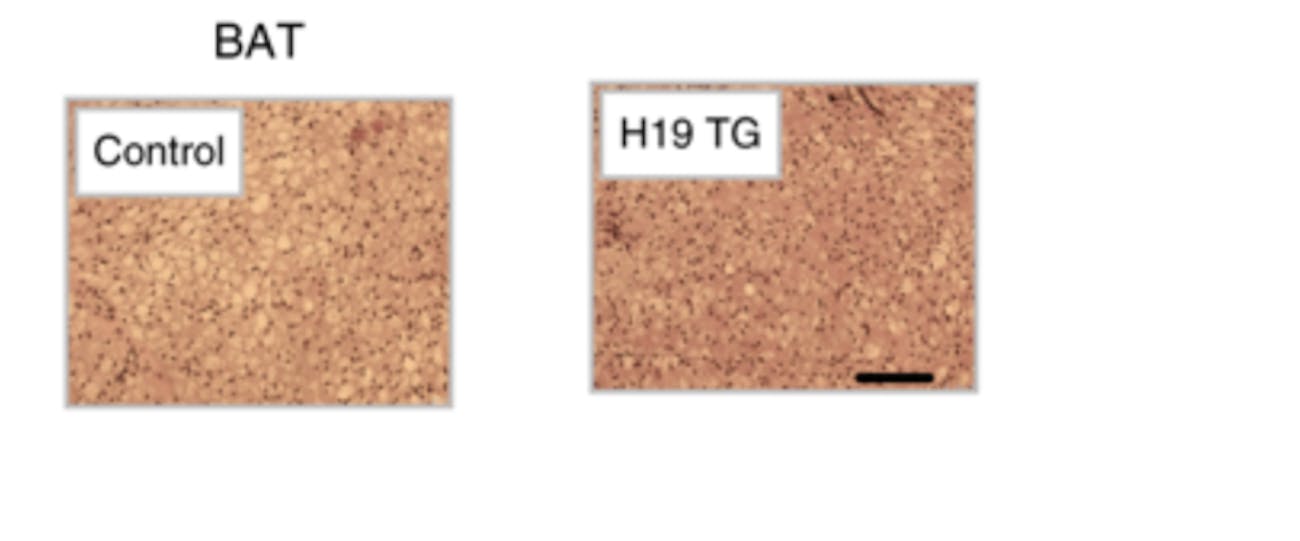

Martin Bilban of the Austrian Medical University adds that they then tested this discovery by genetically manipulating rats to express higher levels of this maternal H19 gene. When they did that, the obese rats that were already rolling in white fat suffered a "beigeing" effect:

"In our models, we can artificially introduce H19 into white adipose tissue. This has not only prevented the build-up of white adipose tissue during obesity, but most importantly, H19 appears to turn white adipose tissue into so-called beige fat tissue, which in some ways resembles brown adipose tissue. for example. It can convert energy into heat as does brown fat.

More studies will be needed to see if this can happen in humans, but in the meantime, we can thank Mother's copy of H19 for making some fat rats a solid.

[ad_2]

Source link