[ad_1]

With years to ponder this epic economic collapse, the seeds of fate were obvious: the rich became richer, their wealth multiplied by generous reductions in income and corporate tax; the remaining 99% of Americans struggle to keep up; a growing personal debt; a period of speculative frenzy; a powerful financial sector with a line of assistance in Washington.

Yes, 1929 was a hellish year. Most of the ingredients that led to the Great Depression were also present before the real estate crash of the United States ten years ago, it's not a coincidence. This is the story that repeats itself.

Even in the Roaring Twenties, we had been there already. In the 19th century, a sharp rise in inequality after the civil war also contributed to the "Panic of 1873" that would trigger a six-year depression in the United States and Europe (the American bank Jay Cooke & Co., founded by the Baron of the railways was the Lehman brothers of his time.)

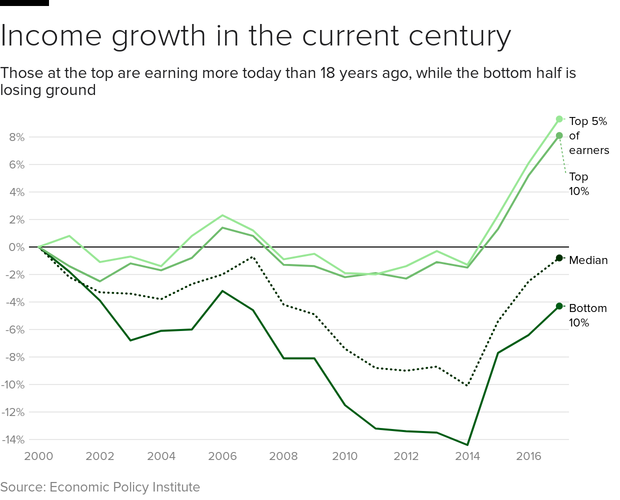

The lesson is clear: to deepen income inequality today should pause in thinking where things can go tomorrow. Because the US economy has rebounded since the real estate crash, it remains in some way extremely vulnerable. The gap between the rich and all the inhabitants of the United States is roughly in 1928. Some warning signs:

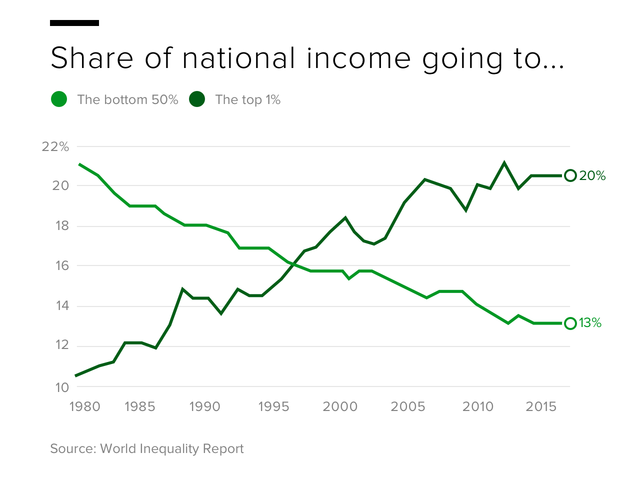

- The share of national income captured by the richest 10% of Americans increased from 34% in 1980 to 47% in 2016.

- Between 1980 and 2016, the share of US income going to the top 1% nearly doubled, while that of the remaining 50% fell.

- After declining as a result of the economic downturn, the top 1% share of the United States was reduced to approximately the 1930s.

- Between 1970 and 2016, the gap between the richest and poorest Americans jumped 27 percentage points.

- Starting in 2017, CEOs of large companies earned on average more than 300 times the salary of a typical worker, compared with 58 times in 1989 and 20 times in 1965.

The path of danger

How does inequality lead to crisis? More fundamentally, as explained economist Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel laureate, allowing the rich to save more than the poor and the middle class. Over time, this redistribution of wealth is eroding the ability of Americans to spend and invest. Demand is shrinking, a syphilis in a consumer economy like the United States.

This trend had already been at work for years when housing prices began to skyrocket in the late 1990s. The dramatic financial deregulation at the end of this decade, coupled with a federal reserve constitutionally bound to cheap money, triggered a wave of reckless and predatory loans. The borrowers were indebted and could never repay, while the homeowners turned their house into ATMs into the illusion that they would pay money forever.

The illusion lasted until the housing bubble appeared – $ 8 trillion in real estate wealth was vaporized. Since then we have been trying to get out of the crater.

Growing inequality is not an American problem alone. Research shows that income and wealth gaps are also widening in China, India and even Europe, where taxation is generally more gradual.

But a host of factors make things worse in the United States, be it high-income tax cuts or unequal access to the usual pathways of upward mobility, such as education and care health.

A blind eye to disaster

Economists point to other parallels between the growing inequality that preceded the Great Depression and what prevailed before the housing crisis that caused the Great Recession. More specifically, millions of Americans have accumulated risky investments – shares, during the previous collapse, of homes in the latter. Financial bubbles have developed. Government policies of "let it go" had let the bankers go wild.

And most importantly, the key players in the two dramas – Wall Street CEOs, financial regulators, central bankers and the owners themselves – were encouraged to steer clear of the storm. The most culpable in 2008 were banks such as Bank of America, Citigroup and of course Lehman, as well as large at-risk lenders like Countrywide, which earned billions by issuing unproductive loans and turning them into securities for savvy investors.

As the bad paper piled up, so-called government watchdogs languished, either "captured" because of their close ties to the very institutions they were accused of, or simply catastrophic. In a speech that became the hallmark of these miscalculations, former Fed chief Ben Bernanke, in May 2007, predicted that the already unresolved issues in the subprime sector would have an impact. " limited "on the real estate market the financial system in general.

Sixteen months later, Lehman declared bankruptcy. Failure was by no means the only one at Bernanke – many regulators, economists, bankers, stock analysts and other "experts" have seen their carefully constructed models fly away. The cardinal sin: a dogmatic adherence to ideas that did not minimize the risks that prevailed in the economy to the point of rejecting them as impossible.

Beyond simply perceiving the link between inequality and financial instability, it is crucial to better understand how changes in US wealth and income patterns can expose the economy. at risk.

For example, the crisis has its roots in the housing market, the foundation of the wealth of most Americans. In contrast, the wealth of those who were higher in the income range was and remains primarily in stocks. It is this group, not the increasingly tight middle class, that has been the main beneficiary of the record bull market that followed the end of the recession.

In short, changes in wealth and income can strengthen the United States or introduce dangerous fault lines. We do not know these cracks in the facade at our peril.

It is therefore not surprising that modest gains in wealth for most Americans, coupled with an increase in wealth for those at the top, now lead to visible inequalities in the economic and political landscape.

Inequality was not the only catalyst for the collapse; many factors have occurred. But it was a fertile soil for the crisis. As usual, it would be wise to learn from history.

Source link