[ad_1]

A devastating viral disease could actually help treat and prevent brain cancer in the future, suggest further research, published Tuesday in MBio. Researchers at the University of Texas and elsewhere have successfully used a modified version of the Zika virus to selectively kill certain stem cells that allow brain tumors to stay alive, at least in mice.

Mainly spread by mosquitoes, Zika has long been considered a minor nuisance. For decades, after its discovery in the 1940s, it has appeared sporadically in Asia and Africa. And when it appeared, it only occasionally caused flu-like symptoms in infected people. But as of 2015, massive outbreaks of Zika raged in South and Central America and in parts of North America. Most of the people who caught the virus this time did not suffer from the experience, but it was soon discovered that Zika could sometimes cause serious birth defects in children whose mothers had contracted her during pregnancy .

These congenital conditions vary from one person to another and may include blindness, deformed limbs and microcephaly, or a smaller head than normal. But they all seem to come from brain damage caused by the virus.

The researchers behind this study, led by Pei-Yong Shi geneticist at the University of Texas, have been studying Zika virus and its close viral cousins for years, hoping to better understand how and why the virus attacks the virus. fetal brain. Unlike related viruses such as West Nile virus, the Zika virus prefers to infect a certain type of cells present in the fetus known as the neural progenitor cell, and their work has shown. And this infection kills and prevents the normal growth of these cells into fully mature neurons.

While their research has focused mainly on the development of Zika treatments – no such drugs currently exist – they have also begun to question whether Zika's sharp appetite can be used wisely.

The most lethal form of brain cancer, called glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), is virtually incurable, with less than five percent of patients surviving five years after their initial diagnosis. Much of what makes GBM deadly is its tenacity: tumors almost always grow back after surgery and chemotherapy.

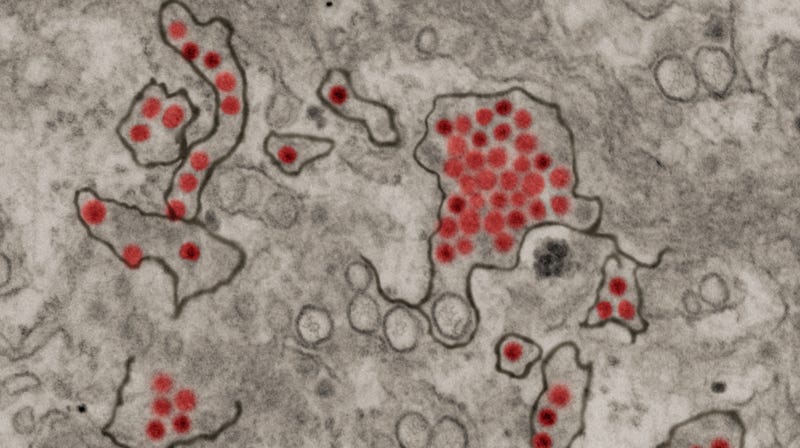

Some scientists believe that GBMs rely on a specific type of stem cells to replenish their ranks, called glioma stem cells. And because these cells strangely resemble the same cells that Zika is looking for in the fetus, Shi and his team theorized that the virus could be re-equipped as an anti-cancer weapon.

In previous research, they found that a typical Zika strain, injected directly into the brain, could prolong the life of mice that developed a form of GBM. But because Zika can still be dangerous for adults, they wanted to work with a more sterilized version of the virus. In this case, the researchers worked hard to create such strains, hoping to develop a vaccine against the disease. So, in their latest experiments, they tested one of these vaccine candidates.

In mice whose immune system is not functioning, the Zika vaccine strain has proven harmless, causing no damage to the brain or altering the behavior of the mouse. It even seemed safer than a live virus vaccine against Japanese encephalitis, another virus transmitted by mosquitoes that attacked the brain. And in mice that had human GBMs grafted onto them, the weakened Zika was still able to kill stem cells and prolong the lives of mice.

"This is obviously just the first step, and there is still a lot of work to be done," Shi told Gizmodo. "But there is a lot to celebrate."

Zika is not the only virus to have been perceived as a potential treatment for brain cancer. Like Zika, the viruses that cause measles and polio also target certain brain cells. And human clinical trials of these viruses, also using weakened vaccine strains, are already underway in patients with brain cancer and have shown promising results.

"We envision that these vaccine-derived viruses are part of a day-long combination therapy with other standard treatments," Shi said. "Like a bullet that goes after these specific stem cells."

Shi and his team plan to continue to unravel the mystery of Zika's unique taste for brains. Understanding this will not only allow scientists to develop new treatments for Zika, but perhaps also to create even safer and more powerful brain cancer treatments.

"We want to train the virus to do even better," said Shi.

[mBio]Source link