[ad_1]

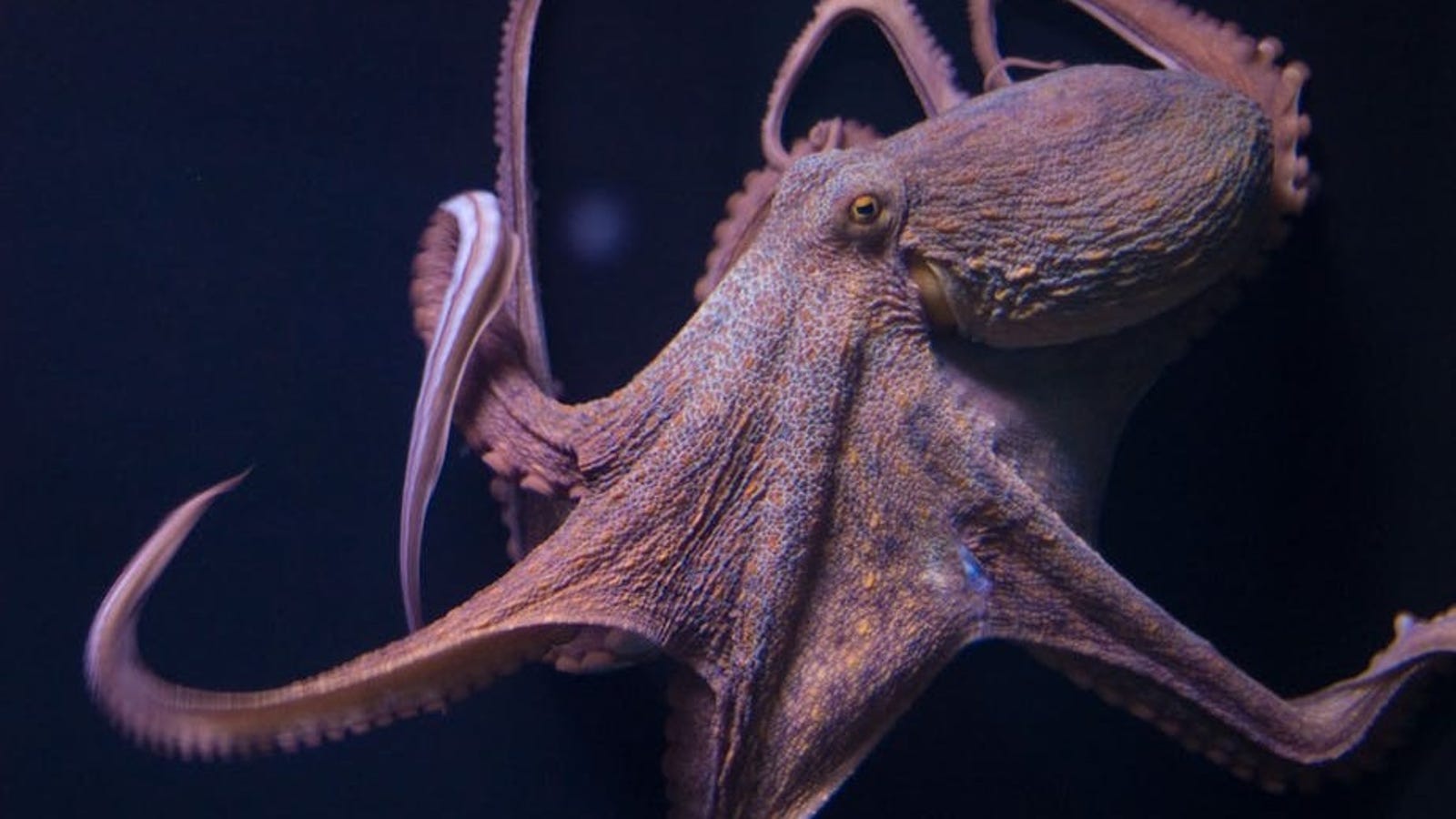

For a female octopus, laying means the beginning of the end.

Like a dedicated hen, she will watch her, caressing the eggs and blowing them with water from time to time, but she will not abandon them for even a second. She will have a welcome snack if the opportunity arises, but after about four days, she will stop eating. And that's when things start to become disastrous.

A week after laying eggs, the behavior of an octopus becomes erratic. Not only does she refuse to eat and eat, but she begins to have openly self-destructive behaviors. Female octopus at this late stage of brooding have been observed to snatch their own skin, eat the tips of their tentacles and groom themselves obsessively to the point of damaging them. Frighteningly, captive female octopi were observed to slam their bodies against the tank.

And then, just as her eggs begin to hatch, she dies.

Her orphaned offspring, with no one to guide them, must navigate and survive alone – a tribute to the intelligence and adaptability of the octopus. But this behavior may also explain why these aquatic animals are such solitary creatures, despite the effects of MDMA.

Scientists gave MDMA to octopus – and what happened was deep

When humans take the drug MDMA, whose versions are known as molly or ecstasy, they often feel …

Read more

Octopuses are what scientists call "semelparous" animals, which means that they only breed once and then die. It is not clear that this is part of the life cycle of the octopus, but there are some theories. Octopuses frequently adopt cannibal behavior, so this biologically programmed death can be a way for nature to prevent mothers from eating their young. Or, because octopuses can grow to huge sizes, this could be an integrated way to protect the ecosystem against too many hungry adults. But the reality is that scientists are still not sure.

As for the physiological processes responsible for this behavior, it's a bit mysterious. But in 1977, scientists discovered that these behaviors disappeared when the optic glands – the octopus equivalent of the mammary pituitary gland – were eliminated from brooding females. With the optical gland gone, the females gave up their eggs, started eating again and even mated. Scientists have realized that they have identified a single "self-destruct" hormone, but new research by Z. Yan Wang, a student at the University of Chicago, shows that it's more complicated than that.

Using gene sequencing tools, Wang and her colleagues have identified several distinct molecular signals produced by the optic gland after breeding female octopus in captivity. These signals were then related to typical maternal behaviors observed in brooding octopus, particularly the California captive two-point octopus held at Wang's laboratory. The researchers removed the multi-phase optical glands from the brooding cycle, allowing them to sequence the RNA transcriptome – the instructions for building proteins – at each stage.

"It's really exciting because it's the first time we can identify molecular mechanisms for such dramatic behaviors, which is for me the subject of the neuroscience study," Wang said in a statement.

Here's what the researchers discovered, as described in a statement from the University of Chicago:

During the non-mating phase, when females actively hunted and ate, they produced high levels of neuropeptides or small protein molecules used by neurons to communicate with each other and related to feeding behavior in many animals. After mating, these neuropeptides fell precipitously.

As animals began to slow down and decline, genes producing neurotransmitters called catecholamines, steroids that metabolize cholesterol, and insulin-related factors were more active. Wang said finding a metabolism-related activity was surprising because it was the first time that the optic gland was linked to anything other than reproduction.

Regarding how these signal changes produce specific behaviors in the octopus that is smoldering, it is not entirely clear. But this new study, published in the Journal of Experimental Biology, presents a new way forward for scientists.

"Before, we only knew the optical gland and we had the impression of watching the trailer of a movie," Wang said. "You have the essence of what is happening, but we are now starting to learn about the main characters, their roles and a little more about the background."

Finally, male octopuses do not have much better either. As Wang points out, females usually kill and eat their mates, otherwise they die a few months after mating. For octopus, sexual maturity is a bit of a mess.

[Journal of Experimental Biology]Source link