[ad_1]

Randy O's Burke at his son's house in Hendersonville, Tennessee. After an overwhelming infection that caused five organ failure in O. Burke, he also developed a delusion in the intensive care unit, possibly related to intense sedation. A resuscitation protocol developed at Vanderbilt University Medical Center revealed that it was essential to get it back on track earlier to speed recovery.

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

Randy O's Burke at his son's house in Hendersonville, Tennessee. After an overwhelming infection that caused five organ failure in O. Burke, he also developed a delusion in the intensive care unit, possibly related to intense sedation. A resuscitation protocol developed at Vanderbilt University Medical Center revealed that it was essential to get it back on track earlier to speed recovery.

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

If you are part of the 5.7 million Americans who end up in the intensive care unit each year, you are at a high risk of developing long-term mental effects like dementia and confusion. These mental problems can be as pronounced as those of people with Alzheimer's disease or traumatic brain injury and many patients never recover fully.

But research shows that you are less likely to suffer from these effects if doctors and nurses follow a procedure that is gaining ground in the ISUs of the country.

The steps are part of a set of actions aimed at reducing delirium in patients undergoing resuscitation. Doctors define delirium as a state of generally temporary mental confusion, characterized by a lack of concentration, a difficulty in understanding what is happening around you, and sometimes hallucinations.

Tracking this list of actions can help reduce the risk of mental retardation by 25 to 30% after a ICU stay, says Dr. E. Wesley's "Wes" Ely at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center. (This post-ICU state is separate from memory problems that may occur after cardiac surgery and general anesthesia in the elderly).

It's not just detailed medical care, it's a philosophy.

"I think the most modifiable part of this process is what we do to the patient," says Ely. "And what we do to the patient [that] is dangerous is immobilize chemically [with drugs] and physically, and then not to allow the family there, and allow them to subsist in delirium. "

When Ely began working in intensive care a few years ago, he realized that each doctor was making different decisions regarding fundamental issues such as the speed with which a patient leaves the device. respiratory. He felt that these small decisions could have a significant impact on the patient's recovery. As a result, he has progressively built a factual checklist of the best way to manage the basic tasks that most quickly enable patients to get back on their feet.

First, medical researchers have developed a system to determine when it was prudent to remove a patient from a ventilator. Then Ely said, "We started normalizing how to remove people from sedation, and then we found a way to measure whether your brain was delusional or not."

Dr. E. Wesley Ely of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville has developed a checklist of procedures in the ICU that reduces long-term mental deficits by reducing sedation, allowing patients to move earlier and helping them stay focused on their environment.

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

Dr. E. Wesley Ely of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville has developed a checklist of procedures in the ICU that reduces long-term mental deficits by reducing sedation, allowing patients to move earlier and helping them stay focused on their environment.

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

Ely dubbed this checklist the ABCDEF packet. Other elements include pain assessment, medication management, verification of patients' ability to wake up spontaneously, and rapid recovery.

Randy O. Burke, 49, recently underwent treatment after being rushed to Vanderbilt with five failed organs: his brain, heart, liver, lungs and kidneys.

His saga began in Los Angeles, where he lives. He had eaten a tuna sandwich which he suspected had gone wrong. The next morning he flew with his wife Karen to visit their son in Nashville.

"We got on the plane and I did not feel well," Randy said. He told his wife that his stomach was bothering him.

The symptoms continued to worsen once in Tennessee. Nevertheless, said his wife, she could not convince him to go to a doctor until his symptoms were out of control. He was rushed to the nearest emergency room at his son's house, half an hour from Nashville.

"They started putting tons of [IV] lines and go to work and do different things, "Karen recalls, everything was unclear to her. Imagine the shock when you go there and [doctors say] "Oh, every organ is stopping." "

O & # 39; Burke was in a septic tank, one of the leading causes of death in hospitals. It is the overwhelming reaction of the body to an infection. The case of O & # 39; Burke was so severe that he was found under respirator and kidney dialysis. The drugs have plunged into a low-key delirium.

"He was supposed to be slightly sedated and he was heavily sedated," says Karen, "and that was not a good thing."

She stated that when the doctors asked her to call the next of kin, she knew it was time to transfer him to a better equipped hospital to treat him. That's how it ended up in Vanderbilt.

In the 24 hours that followed his arrival, Randy's condition was completely transformed, says Karen. He was on dialysis, the ventilator and drugs that plunged him into a delirious mist.

"Apparently, I'm pretty much a miracle," he says. Doctors told him that the chances of survival of a patient with a failure of five organs were about one in a thousand.

The recovery is yet to come, as suggested by his slightly hazy speech.

"I'm starting to have my faculties on me," Randy says. "My brain is starting to work really well again, but the fact that I can continue a conversation now is pretty amazing in itself."

As part of this faster recovery trajectory, nurses from intensive care units have it out of bed as soon as possible.

"I've been doing tricks around this place!" he says.

O & # 39; Burke has recovered a tremendous amount of medical care. The package of measures to reduce delirium was covered. These are now included in the checklists that nurses, respiratory therapists and physicians use with each patient in the intensive care unit treated at Vanderbilt.

"You get out of bed early … cut the delirium in half," Ely told O & # 39; Burkes, explaining the reasoning behind the package. "E" means early mobility and exercise. And "F" – the presence of family members in the room and discussion with medical staff – also helps to motivate patients to stay alert and move.

Ely explains to the couple that this set of procedures is a significant change from what many ICUs continue to do: knock out a patient and treat their dysfunctional body instead of focusing on it in a holistic way.

"For me, the pivot of all this is to respect the humanity of every patient," says Ely.

The Vanderbilt protocol, when consistently followed, can make a big difference for many patients. A study of 6,064 patients showed that this approach increased the chances of survival and reduced time spent in delirium or coma.

Ely is the lead author of another study involving a network of intensive care units that included 15,000 patients. The results of this forthcoming study provide additional support for the practice, says Ely.

Gradually, the package of techniques to reduce delirium has been adopted by many ICUs in recent years, says Ely, but is still not the norm everywhere.

"About half [of hospitals] from our last survey were some elements of the package, "he says.

Pulling it all together, from A to F, can be a challenge.

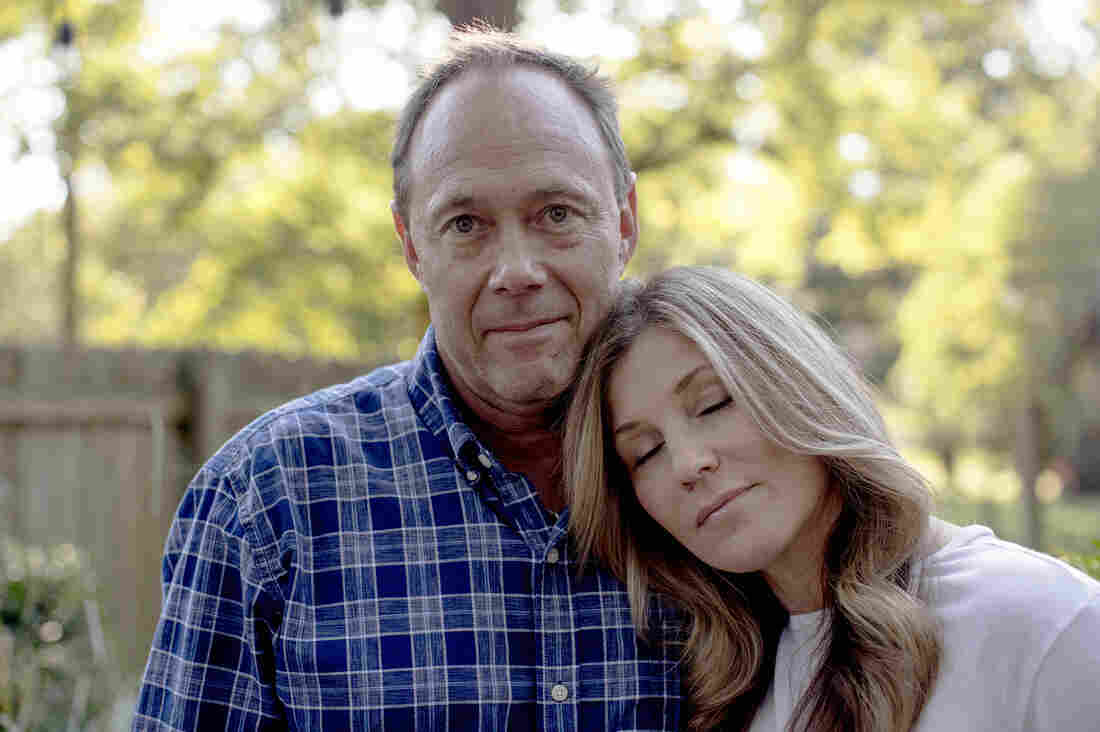

Randy and Karen O 'Burke together at their son's home in Hendersonville, Tennessee, last week. "Apparently, I'm pretty much a miracle," Randy says.

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

hide the legend

activate the legend

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

Randy and Karen O 'Burke together at their son's home in Hendersonville, Tennessee, last week. "Apparently, I'm pretty much a miracle," Randy says.

Morgan Hornsby for NPR

"This has not been as easy as expected," said Dr. Kirk Voelker, ICU Specialist at Sarasota Memorial Hospital in Florida. His hospital was part of the 15,000-patient study coordinated by Ely.

Voelker says that he has discovered that patients may need more time and attention if they are bed alert or walk up and down the hallway with their respirator in tow.

And for the staff, "we are talking about a cultural change," he told NPR. "We had to get the nursing membership in. Once we were able to get that commitment, you also need to get the agreement from the doctors."

It's more difficult in a community hospital, he says, where doctors are more independent and can only tour three days a week.

Ideas have slowly taken root, he says, although there is still resistance to using the checklist "A to F" to make sure every item is taken care of every day for every patient .

The concept behind the protocol has become the rule in his hospital, says Voelker, "but in reality, saying" ABDCEF "is the exception.

It was even a challenge to do the protocol routine at the medical center where it was developed.

Joanna Stollings, a clinical pharmacist from the Vanderbilt Intensive Care Unit, said that upon her arrival at the hospital, it was clear what to do, but no one was able to do it. He was responsible for carrying it out.

"He needs someone to coordinate that, who will be here every day," she says. "And then Wes [Ely] I have helped somehow to defend this project, to give nurses and respiratory therapists the means to make that happen every day. "

Ely's mission is now to do what his hospital does standard around the world. On the one hand, it can actually reduce the cost of care, he says, reducing the time people spend in expensive USU units.

"But the most important thing, of course, is not money, it's the human being," he says. "So, if they get better care, survive longer – often with a more intact brain – and do not bounce back to the USI … for me, it's a win-win situation. "

You can contact Richard Harris at [email protected].

Source link