[ad_1]

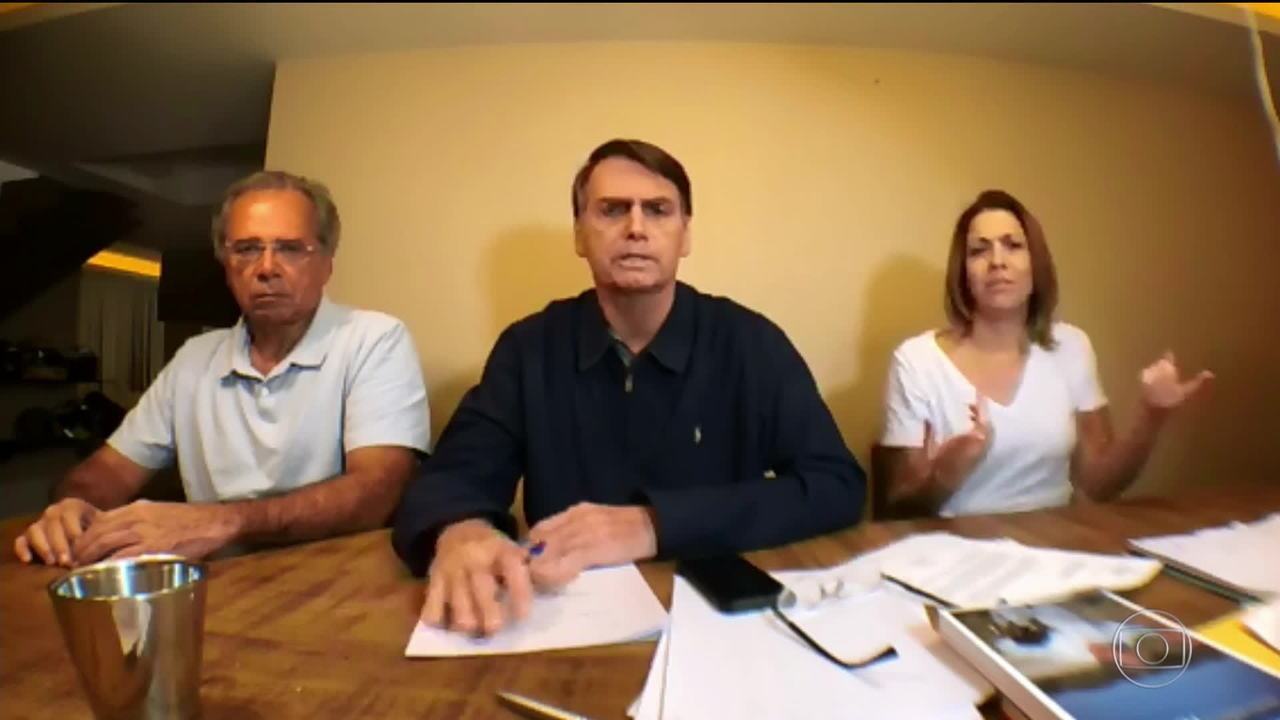

Bolsonaro represents Brazil's elected officials

Brazil's elections on October 7 presumed to be a result predictable result, a presidential polls Jair Bolsonaro and left-wing Fernando Haddad.

There were, however, some surprises in there, such as the astounding increase of party fragmentation in Congress, the amazing success of Mr. Bolsonaro's party in legislative races, the crushing defeats of political elections and the gubernatorial elections, and the unexpected rise of some candidates for governor.

In 2019, our party will be more than 30 years old, with a grand total of 30 parts represented in the lower house. The effective number of parties, a concept used in political science to measure the real weight of parts in a legislature, went up to 16.5 – as Calculated by political scientist Jairo Nicolau.

It is not only the highest index in the world, it is also three times the number of parts in Belgium (less than 6), which comes in second. The highest number ever registered in Europe came in the old Czechoslovakia, with 10, between 1920 and 1938.

The next president will have a hard time organizing his support base, as coordinating so many parts in the same direction is no easy task. Besides, important parties such as President Michel Temer's Brazilian Democratic Party Movement, the Brazilian Social Democracy Party, and the Democrats Party were badly wounded. The first dropped from 51 seats in the lower house to 34; the social democrats went from 49 to 29, and Democratas fell from 43 to the same 29.

Insignificant before Sunday, the Social Liberal Party is now the second-biggest party in the House, electing 52 members of the Congress and trailing only the Workers' Party, which has 56. That number could have been even larger (7 seats more) if it is not elected for a new electoral rule, according to which candidates do not have enough votes to meet the electoral quotient are not elected.

In São Paulo, one of Mr. Bolsonaro's sounds, Eduardo, was the best-voted candidate for Congress in history, with 1.8 million votes. He alone could have secured 15 extra seats for the party.

The next president's relationship with Congress

What we've seen on Sunday was a brutal shift to the right in the lower house: from 238 congressmen four years ago to 301 now – most of them coming from minnow parties. That growth has been fairly stable, with the workers' party and their satellite versions stronger.

A similar thing happened in the Senate, where centrist parties lost 10 seats (of 81), while the right-wing snatched 11 seats. The left, meanwhile, lost to one of the seats, with the Workers 'Party being smaller and Rede (Marina Silva' s environmentalist party) jumping from one to five senators.

Either presidential candidate has the ability to build a coalition, but it is also important to ensure that the membership is successful. But Mr. Bolsonaro will undoubtedly have better conditions to govern.

Congressional races were clearly affected by the national clash. What else would explain the Eduardo Bolsonaro phenomenon? Or the 2 million votes (for state assembly) given to a lawyer who has gained notoriety during Dilma Rousseff's impeachment process and was considered a potential running mate of Mr. Bolsonaro?

The far-right candidate is also interested in the Senate and state governments. Major Olímpio cruised to an upset in São Paulo, dethroning longtime politician Eduardo Suplicy. In Rio de Janeiro, another of Mr. Bolsonaro's sounds, Flavio, is a member of the Workers' Party and a mayor of Rio. In Minas Gerais, President Dilma Rousseff did not get back to Brasilia through the Senate. These establishment candidates were favored to win-but failed, as

The biggest upsets

No upsets, however, were bigger than what happened in Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro's gubernatorial breeds. The second and third most-populated states, respectively, saw meteoric rises from two little-known candidates after they declared their support to the far-right candidate.

In Minas Gerais, retail mogul Romeu Zema, from the libertarian-conservative Novo party, asked voters to choose "new candidates, like me and Bolsonaro." In Rio de Janeiro, Witzel Wilson, a judge with a rhetoric authoritarian, shot up in the polls over the last days of the campaign, thanks to support from Mr. Bolsonaro and Rio's public safety chaos.

Mr. Zema went from 9 percent in polls late in September to 19 percent on the eve of the election, to 43 percent of the valid votes (spoiled ballots aside). Mr. Witzel's final sprint was even more impressive. On October 4, he had a grand total of 11 percent of voting intentions, to 17 percent on October 6, to 41 percent of the valid votes in the final count.

Many quickly called out the polls, saying they could not have been more wrong. But the problem is in which we read those polls. State races get little attention from voters, especially when the national race becomes so polarized. When voters finally realize what is at stake in the local levels, it is in the last moments – which create decisions often perceived as sudden and surprising.

In the first part of the campaign, voters' answers to pollsters are more based on their level of knowledge of the candidates. Only as the election approaches is when they look more carefully at who's on the nerd. In a country swept by anti-establishment feeling, "new" guys get stronger. The wave that fueled Mr. Bolsonaro was also fueled by him – helping candidates like himself. If he wins, that will be very helpful for a future administration. If he loses, he will have the muscle to play hardball.

Tags: 2018 election, Jair Bolsonaro

[ad_2]Source link