[ad_1]

For decades, many researchers have tended to view astrobiology as an outsider of space science. The field – which focuses on the investigation of life beyond the Earth – has often been criticized as more philosophical than scientific because it lacks concrete samples to study.

Now everything is changing. While astronomers once knew no planet outside our solar system, they now have thousands of examples. And although it was previously believed that organisms needed the relatively mild surface conditions of our world to survive, new discoveries about the ability of life to persist in the face of extreme darkness, heat , salinity and cold have increased the belief of researchers that it could be found anywhere. Martian deserts in the frozen oceans of the moon of Saturn, Enceladus.

Highlighting the increasing maturity and influence of astrobiology, a new report from the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) mandated by the US Congress urges NASA to search for life on other worlds a central and central element of its exploration efforts. The field is now well positioned to be a major motivation for the agency's future mission portfolio, which could someday let humanity know whether or not we are alone in the universe. "The opportunity to really address this issue is at a critical juncture," says Barbara Sherwood Lollar, a geologist at the University of Toronto and chair of the committee that wrote the report.

The planetary and astronomy communities are currently preparing to conduct their 10-year surveys – efforts every 10 years that identify the most important outstanding issues in a given area – and present a list of projects that can help to reply. Congress and government agencies such as NASA are turning to decennial surveys to plan their research strategies; in turn, decade-olds are turning to documents such as the NAS's new report for authoritative recommendations on which to base their conclusions. The fact that astrobiology now receives so much encouragement could strengthen its chances of becoming a ten-year priority.

Another NAS study released last month could be considered a second vote in favor of astrobiology. This report entitled "Exoplanet Science Strategy" recommended that NASA lead efforts on a new space telescope that can directly capture light from Earth-like planets around other stars. Two concepts, the Large Ultraviolet / Optical / Infrared Telescope (LUVOIR) and Habop Exoplanet Habitual Observatory, are now candidates for a multi-billion dollar NASA flagship mission that would steal as soon as possible. the 2030s. The two observatories could use a coronograph, or "starshade", objects that selectively block the light of the stars while letting the planetary light through, looking for signs of livability and life in distant atmospheres. But one or the other would need massive and sustained support from outside astrobiology to succeed in the ten year process and beyond.

Previous efforts had already been made to support large-scale, astrobiology-focused missions, such as NASA's Earth Finder Planet concepts – ambitious space telescope proposals in the mid-2000s that would have detect exoplanets the size of the Earth and characterize their atmospheres (if these projects had already done the drawing board). Instead, they suffered ignominious cancellations that taught astrobiologists several difficult lessons. Caleb Scharf, an astrobiologist at Columbia University, did not yet have enough information on the number of planets surrounding other stars, which means that defenders would not be able to correctly estimate the chances of success of such a star. mission. Her community had yet to realize that in order to make big plans they had to regroup and show how their goals fit with those of astronomers who are less interested in the search for extraterrestrial life, he said. added. "If we want big toys," he says. "We have to play better with others."

According to Jonathan Lunine, scientist in planetary sciences at Cornell University, there were also tensions in the past between the astrobiological goals of solar system exploration and the more geophysical goals that underpin efforts of this type. Missions on other planets or satellites have a limited capacity in instruments and those specialized in different tasks often find themselves in fierce competitions for a time slot. Historically, since the search for life was so open and difficult to define, the associated instrumentation was lost in favor of the material, with clearer and more limited geophysical research priorities. Today, explains Lunine, a growing understanding of all the links between biological and geological evolution makes it possible to show that such objectives do not have to be contradictory. "I hope that astrobiology will be an integral part of the global scientific exploration of the solar system," he said. "Not like an add-on, but as one of the essential disciplines."

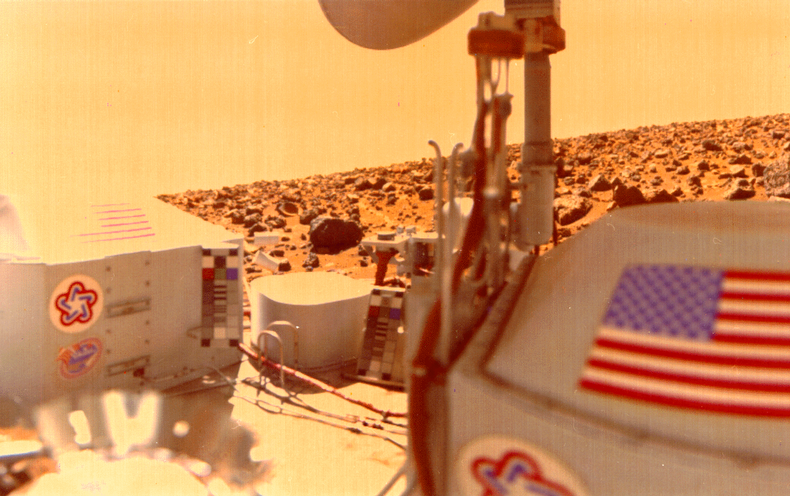

Beyond the recent NAS reports, it can be argued that NASA already shows more interest in searching for life in our cosmic backyard than it has in decades. This year, the agency has published a request for experiments likely to be transferred to another world of our solar system in order to directly search for evidence of the presence of living organisms – the first of this type since the 1976 Viking missions in search of life on Mars. "The Ladder of Life Detection," an article written by NASA scientists and published in astrobiology in June, presented ways to clearly determine if a sample contains extraterrestrial creatures – a goal mentioned in the SIN report. The paper also suggests a partnership between NASA and other agencies and organizations working on astrobiological projects, as did the space agency last month when it organized a workshop with the SETI non-profit institute on the search for "techno-signatures", potential indicators of intelligent extraterrestrials. "I think astrobiology has gone from something that seemed dashing or distracting to something that seems to be considered by NASA as a major touchstone for why we're doing space exploration and why the public cares about knowing, "says Ariel Anbar, geochemist in Arizona. Tempe State University.

All that means is that the growing influence of astrobiology is helping to materialize what once were considered bizarre ideas. Anbar remembers attending a conference in the early 1990s, when NASA's administrator, Dan Goldin, had then shown an image of the Earth dating from Apollo and had suggested it to him. Try to do the same for a planet around another star.

"It was pretty there 25 years ago," he says. "Now it's not there at all."

Source link