[ad_1]

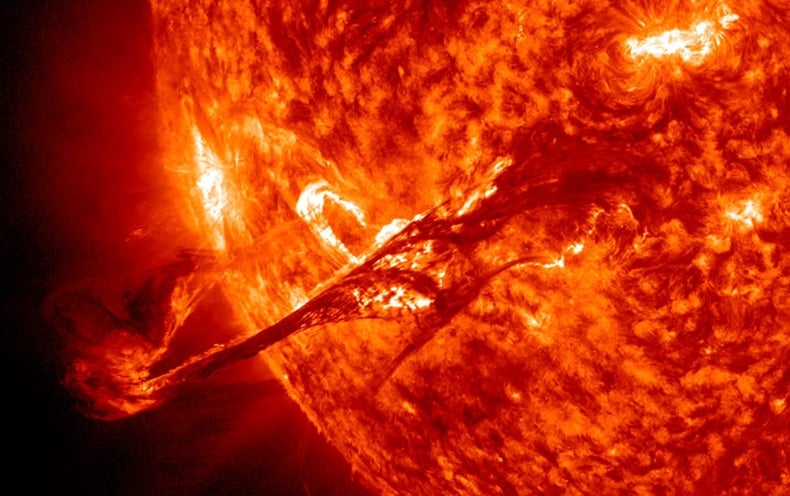

We live together on the surface of a smallish rock in the immediate neighborhood of an angry plasma death-ball that gives us the energy we need to survive but could also swallow our entire home with nary a burp.

So, you know, sometimes this plasma ball causes problems. Like blowing up a bunch of underwater mines during the Vietnam War, according to a paper published Oct. 25 in the journal Space Weather.

“Space weather” is a collective term for the various energetic gobbets the sun periodically, unpredictably vomits in our general direction. Those gobbets are usually mild, but can be quite powerful. Scientists don’t know exactly how often they occur, and the blobs of energy have the potential to do all sorts of damage, from frying the global satellite infrastructure to drastically messing things up for life on Earth. The most powerful example on record was studied in 1859, and its effects were noticed primarily by skywatchers, telegraph operators and folks who spotted the weirdly southern auroras it created. If it happened in our modern electrified era, its consequences would be much more serious.

There have been major space weather incidents since, though none on the scale of the 1859 event. And researchers are still figuring out the extent of their potential for damage. In the Space Weather paper, the researchers dug up old Navy records that suggest a famous 1972 solar storm was even more serious than they had realized. [Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets]

“Between 2 and 4 August 1972 [a sunspot] produced a series of brilliant flares, energetic particle enhancements and Earth-directed ejecta,” they wrote.

Those flares cleared the path for “the subsequent ultra-fast… shock… that reached Earth in record time—14.6 hours.”

People all over the planet noticed that flare’s effects.

“Dayside radio blackouts… developed within minutes. X-ray emissions from the long-duration flare remained [high] for [more than] 16 hours. For the first time, a space-based detector observed gamma-rays during this solar flare. [Experts] rated the flare at Comprehensive Flare Index level 17—the highest level, and one assigned to only the most extreme and broad-spectrum flares“ they wrote, adding that “‘spectacular aurora,’ bright enough to cast shadows, appeared along the southern coast of the United Kingdom… Within two hours commercial airline pilots reported aurora as far south as Bilboa, Spain.”

Researchers later found that the flare caused damage to solar panels on satellites in space; a defense communications satellite “suffered a mission-ending on orbit power failure;” and Air Force sensors switched on, suggesting falsely that a nuclear bomb had detonated somewhere on the planet.

“This is one of only a handful of events in the space age that would have posed an immediate threat to astronaut safety,” the researchers wrote, “had humans been in transit to the moon at the time.”

And somehow, amid all that drama, space weather researchers had largely ignored another consequence of the storm: “the sudden detonation of a ‘large number’ of US Navy… sea mines [that had been] dropped into the coastal waters of North Vietnam only three months earlier.”

Pilots flying over the area spotted about two dozen explosions in a minefield in just a 30-second period, the researchers wrote.

Naval researchers investigated, and they ultimately concluded the blasts were the result of the solar storm triggering magnetic sensors in the mines that had been primed to detect passing metal ships.

According to the researchers, this event led to major changes within the Navy, which rapidly researched alternatives to the magnetic sensor mines that would be more resistant to solar effects. However, the story never really made its way over to the space weather research community.

Now, the researchers said, this event illustrates the modern challenge of figuring out how storms like this (or those even more powerful) would impact modern infrastructure. And it’s still unclear, they wrote, what features of the storm made it so intense. Was it the speed of the flare? The multiple flares clearing a path through space before the big one? The magnetic environment around Earth at the time?

It’s still unclear, they wrote, what a powerful solar storm might do to critical satellites, or how common it was. In July 2012, a major storm narrowly missed Earth, instead hitting nearby satellites. How did it compare?

There are still just too many unknowns.

Copyright 2018 LIVESCIENCE.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Source link