[ad_1]

People more likely to call men by their last name, attach prestige to doing so.

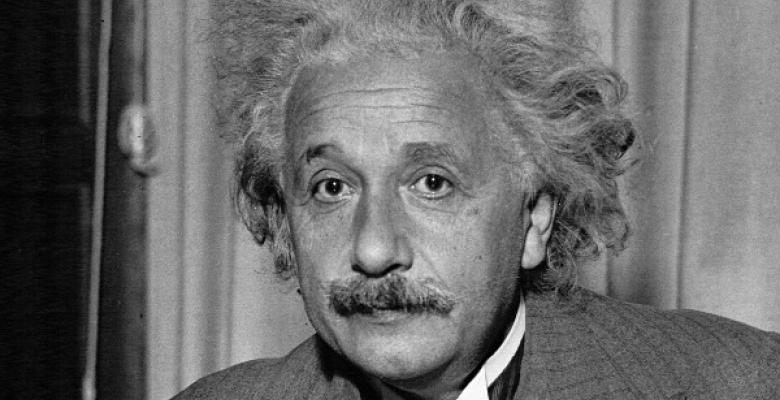

When we talk about the most famous scientists, we are often on a family name basis. For figures like Darwin and Einstein, first names and even titles like "teacher" seem out of place. We know who they are, and only one name is enough to evoke all that they have accomplished.

But can you think of women scientists where the same thing is true? A new study suggests that using the surname of a scientist can help perpetuate a prejudice against women scientists. A variety of studies show that people are more likely to refer to men than by their last name. And a set of separate experiences indicates that people will attach more prestige to anyone deemed worthy to be named by their last name

True in Politics and Science

Studies were conducted by Stav Atir and Melissa Ferguson of Cornell. The first set asked a relatively simple question: is there evidence of a sexist bias by referring to people by their last name?

To discover them, both took advantage of some available data sources. One is simply the transcription of various information programs on the other side of the ideological spectrum (19459007). All Things Considered Fresh Air Morning Edition The Rush Limbaugh Show and The Sean Hannity Show ). References to individuals have been identified, as have the gender of those referred to. The researchers then determined if the individual was mentioned only by his last name, without using initials or titles like Doctor or Professor. On the radio, at least, people were twice as likely to refer to men using only their last name.

To see if this can be true in an academic context, Atir and Ferguson are turning to Rate My Professors, a service that allows students to do exactly what his name implies. Data were aggregated for teachers from five departments (biology, psychology, computer science, history and economics) in 14 different universities, with the same search for references based on professors' last names. Students during the rating were more than 50% more likely to reserve name references for male teachers. Atir and Ferguson checked if the genre was simply acting as a substitute for the professor's seniority, but that turned out not to be the case.

Moving directly to science, the researchers compiled a list of scientific achievements. randomly attached to a masculine or feminine name. This was given to about 200 participants at Mechanical Turk, who were then asked to describe the researcher. If the profile had a male name, people were four times more likely to refer to the fictitious person using only their last name.

There is therefore a clear tendency to treat the sexes differently when we communicate about them, and it seems to extend to science. With this established, Atir and Ferguson turned to whether this trend has consequences

Biased Perceptions

To find out, researchers have prepared a series of research proposals and have randomly substituted full names and family names for the researcher the work. The participants in Mechanical Turk felt that the researchers referred to by their last name were better known and more prominent (though, curiously, not more distinguished). They also noted that researchers who were only mentioned by their last name were more likely to win a prize for their work. When given the option of dividing funds for different research projects, participants awarded more to all the researchers mentioned only by their last name.

It is important to recognize the limitations of this study. It is unlikely that people recruited from Mechanical Turk will be the same as those recruited by the foundations to revise their grants, so the direct relevance for scientific rewards and rewards is likely limited.

But it's not the same thing. not important. While the process of science as a whole tends to limit the impact of subtle biases like this, individual scientists are just as prone to their influence as any other human. Many scientists also use popular accounts to track news outside their domain and so they might take a biased view of it. Finally, the popular perception of scientists also plays a role in the scientists and the fields in which they specialize.

Since there are still significant gender disparities in countries that have made significant progress towards equality, such subtle problems are worth it. A follow-up where the use of the name by the scientists was examined directly certainly seems appropriate.

For their part, Atir and Ferguson are curious as to why this bias was committed in the first place. They suggest possibilities such as the fact that some women change their name after marriage or the fact that women's first names seem more descriptive in areas dominated by men.

Regardless of its cause, being aware of the potential of this bias is essential to limit its influence. That's to say, at least until the day it becomes usual to talk about people like Dresselhaus and Nüsslein-Volhard as regularly as we do Darwin and Einstein.

PNAS 2018. DOI: 10.1073 / pnas.1805284115 (About the DOIs).

Source link