[ad_1]

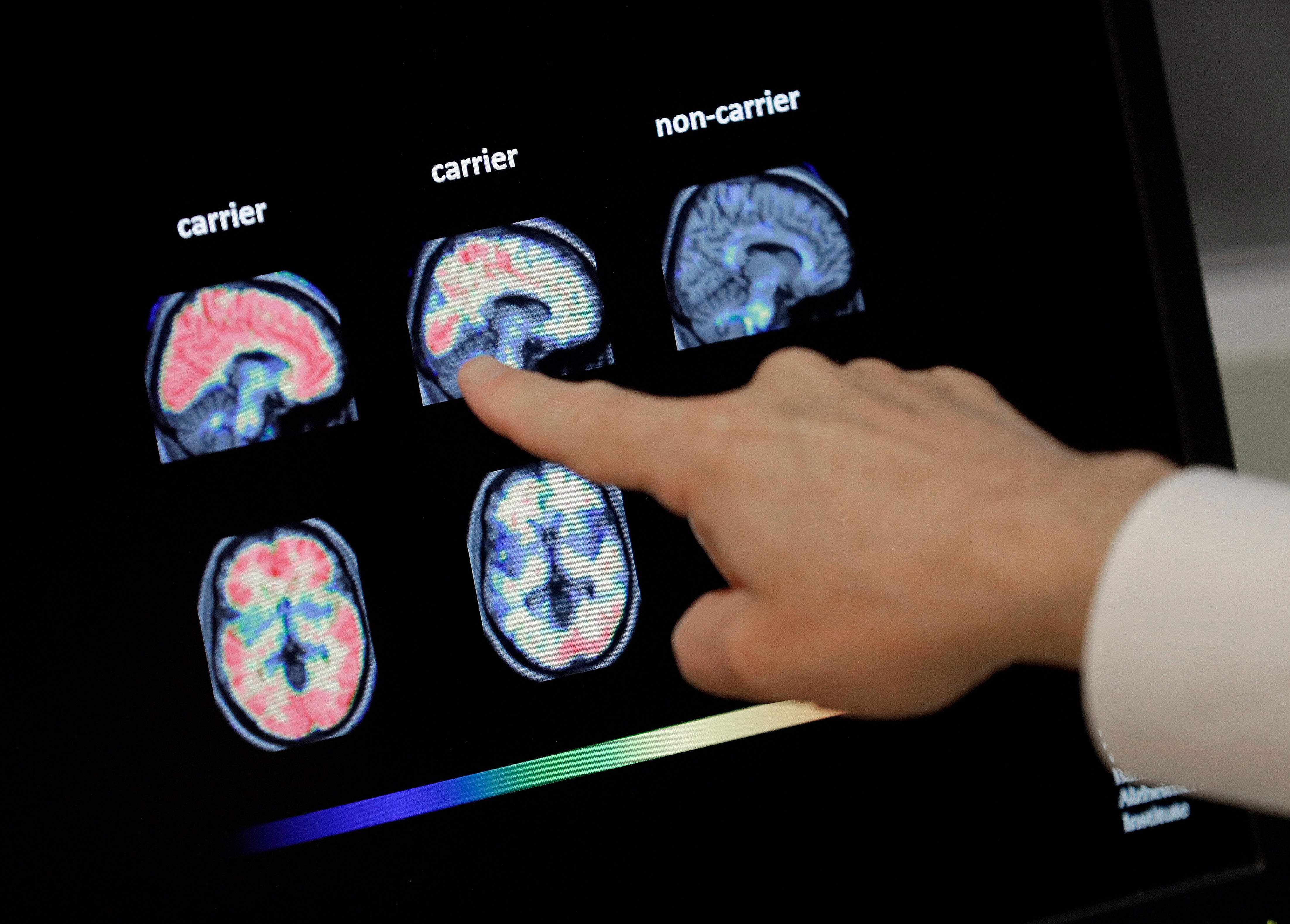

Banner The Alzheimers Institute in Phoenix is currently conducting two studies on the earliest brain changes, while preserving memory and thinking skills, in the hope of preventing the disease.

It may be too late to stop Alzheimer's disease in people who are already suffering from some mental decline. But what if a treatment can target the very first brain changes while the memory and thinking skills are still intact, hoping to prevent the disease? Two large studies are being tried.

Clinics across the United States and some other countries have recruited participants – the only studies of this type to recruit healthy older people.

"Prevention in the field of Alzheimer's disease is right now related to prevention," said Dr. Eric Reiman, executive director of the Banner Alzheimer's Institute in Phoenix, who directs the work.

Until now, science has failed to find a drug that can alter the progression of Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia. A recent industry report revealed that 146 attempts had failed over the past decade. Even medications that help clear the sticky plates that clog the brains of people with the disease have not yet managed to stop the mental decline.

PREVENTING TUMOR PROPAGATION COULD NOT IMPROVE QUALITY OF LIFE

They may have been judged too late, for example to lower cholesterol after a heart attack whose damage can not be repaired, said Reiman.

"What we have learned painfully is that if we really want to offer treatments that will change the disease, we have to start very, very very early," said Dr. Eliezer Masliah, head of neuroscience at the University of California. National Institute. on aging.

His agency funds prevention studies with the Alzheimer's Association, several foundations, as well as Novartis and Amgen, makers of two experimental drugs on trial.

The goal is to try to block the early stages of plaque formation in healthy people who have no symptoms of dementia, but who are at a higher risk of developing dementia because of their age and a gene that makes it more likely.

To participate, people must first register for GeneMatch, a confidential registry of people interested in volunteering for various studies of Alzheimer's disease aged 55 to 75 years and not diagnosed with mental decline. .

They are controlled for the APOE4 gene, which does not target anyone to develop Alzheimer's disease, but increases that risk. About one in four people own a copy of the gene and about 2% have two copies, one from each parent.

More than 70,000 people have registered since the start of the registry three years ago, said Jessica Langbaum, one of the leaders of the Banner study.

"Most of them have been personally affected by the disease," either by having a family member or a close friend with her, she said.

RESEARCHERS DEVELOP ALZHEIMER'S FIRST TREATMENT IN THE WORLD, STUDY CLAIMS

Ivy Segal, Langbaum's mother, aged 67, gave a DNA sample with the help of a cotton swab and joined the registry in August. His father was a Banner patient and died of Alzheimer's disease in 2011, at the age of 87. Watching him pass from a man with gentle manners whose smiles would light up a room, what it was like his death was devastating, she said.

Being in GeneMatch does not necessarily mean that you will know if you have the gene – people with and without it can be contacted about various studies. But to participate in one of two prevention studies, people must agree to learn their APOE4 status and to have at least one copy of the gene.

Participants undergo periodic brain exams, as well as memory and reflection tests every six months. They receive experimental drugs or placebo versions for several years.

One study recruits people with two copies of the gene. Every few months, they are given a medicine to help the immune system to eliminate brain plaque or daily tablets of a drug intended to prevent the early stages of plaque formation, or even placebo versions of these experimental treatments.

The other study is about people who have either two copies of APOE4 or a copy of the gene, plus evidence that plaque is starting to form in the brain. They will receive one of two doses of the drug to prevent plaque formation or placebo pills.

Larry Rebenack, 71, from the suburbs of Phoenix to Surprise, Arizona, joined GeneMatch in August.

"I have a lot of friends and acquaintances that I've seen deteriorate," including one that started blowing through stop signs to get to a golf course that they had traveled safely for years and another who forgot not only where he had parked his car but even what type of car he was operating, said Rebenack. "It's a disease that takes away a small part of you each day."

Rebenack decided to know if he has the gene if the researchers give him the opportunity.

"It's like any other information that helps you plan your life and you owe it to all your loved ones as well."

Source link