[ad_1]

A comparison of surveys conducted between sky and sky revealed an empty space where a star was once 280 million light years.

Coded FIRST J1419 + 3940, the object records suggest what would have been a violent death. Curiously, there is no trace of his last explosive moments – but this ghostly silence has only made astronomers even more excited.

"We compared images of old maps of the sky and found a radio source that was no longer visible today in the VLASS (Very Large Array Sky Survey)," explains L & # 39; Casey Law astronomer of the University of California at Berkeley.

"Looking at the radio source in other old data shows that she lived in a relatively close galaxy and, in the 1990s, she was as bright as the biggest known explosion, gamma ray bursts."

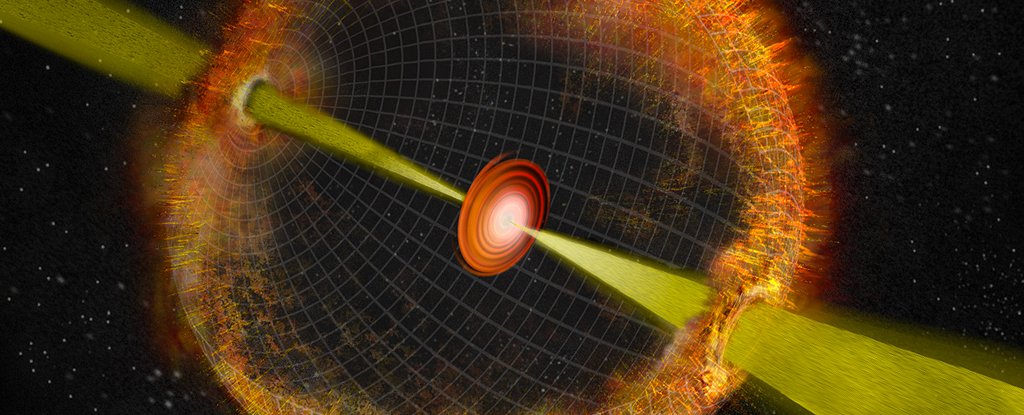

Gamma ray bursts (GRB) are the cosmological equivalent of lightning on the galactic horizon. They are sudden, brilliant and release enormous amounts of energy in the most violent explosions of the Universe.

The mechanisms at the origin of these intense floods of light are not well understood, but they seem to be caused by the final collapse of massive stars while gravity claims victory over their cold body, or the fusion of neutron stars.

Although technically rare, they are bright enough to be detected in other galaxies, giving us many opportunities to spot them. In fact, we should expect to see about 500 a day on average.

But there is a catch. The amount of energy behind the flash indicates that it is most likely in the form of a channeled beam rather than a well-distributed bright light sphere.

This means that we would see them only when these beams are directed directly at us, limiting our observations to a derisory observation a day. And that's only if we can find them.

The discovery of J1419 + 3940 may well change all that.

"Its maximum brightness in the 90s was quite high, so it was a very big change: a brightness about 50 times smaller," says Law.

"We basically looked at all the radio surveys, all the radio data sets we could find, all the archives of the world, to reconstruct the history of what happened."

The story they agreed on suggests that this should have resulted in an intense flash of intense gamma rays immediately before disappearing.

It was in the right neighborhood – a dwarf galaxy – for the right kind of stars, and lit up like a supernova. It was more than likely an object about 40 times the mass of our own Sun, which ended up becoming a black hole or a highly magnetized neutron star.

On the basis of such estimates, they should have seen a submarine minute of this region in 1992 or 1993. Unfortunately, no singing of this swan song could be seen. Just the vibrant glow of radio waves, like the embers of a dying fire.

These radio waves have since disappeared. The 2017 VLASS has not found anything.

Either they were mistaken about the GRB, or our multitude of sensitive telescopes was simply not in the line of fire. If this last reason were true, it would be the first observation of a GRB event without detecting real gamma rays.

"It's exciting, not just because it's probably the first" under-orbit "to be discovered," says Law.

It is believed that gamma rays penetrated the expanding gas envelope released by the supernova explosion, resulting in a shock wave in the form of detectable radiation in the form of radio waves. at relatively low energy.

Finding more of these shock waves could tell us a lot about these awesome phenomena. For example, we could compare the number of orphan streetlights to the number of bursts to improve our accuracy on the characteristics of these powerful jets.

Given that the VLASS will perform several sweeps of about 80% of the sky over the next seven years, it is more than likely that we will collect more examples of missed GRB, in order to provide a more accurate picture of their prevalence and their distribution.

"This shows the exciting capabilities of the new generation of large-field radio surveys," said Bryan Gaensler, director of the Dunlap Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics of Northumberland. University of Toronto.

"There are dramatic and dynamic explosions and flares, but we can only find them if we can constantly patrol the sky to see what's changing."

This search was accepted for publication in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Source link