[ad_1]

Looking up, the morning of Monday, September 15, 2008 is peaceful, but the atmosphere is palpable, heavy.

I'm looking forward to the Lehman Brothers headquarters in Midtown, Manhattan, and I'm getting ready to go live to report on the biggest bankruptcy of companies in US history. Three years after my journalistic career, I now cover what will probably be one of the biggest stories of my life.

I watch the workers solemnly leave the building, looking exhausted and incredulous. These former Lehman employees, carrying these paper filing boxes, each containing small trinkets and job memories, have now disappeared.

Employees tell me that they are angry at their company, their country, that they have never hoped to be here, and that they have no idea what will follow.

Ben Stansall / AFP / Getty Images, FILE

Ben Stansall / AFP / Getty Images, FILE

A few are new employees, asked the previous Friday to report to work as usual.

The financial crisis has already resulted in a series of destructions. Layoffs and foreclosures are up. The stock market sinks deeper every day. You can feel the hustle and bustle wherever you go: the grocery store, the gas station, the baseball game – and especially Wall St.

There is an underlying panic waiting for you. It becomes the powder keg lit by the match that is the bankruptcy of Lehman. The brutal reality is installed not only for the employees of Lehman, but for the workers of the country. There is tremendous uncertainty for US companies and employees around the world – if Lehman can break down, anything is possible.

Robyn Beck / AFP / Getty Images

Robyn Beck / AFP / Getty Images

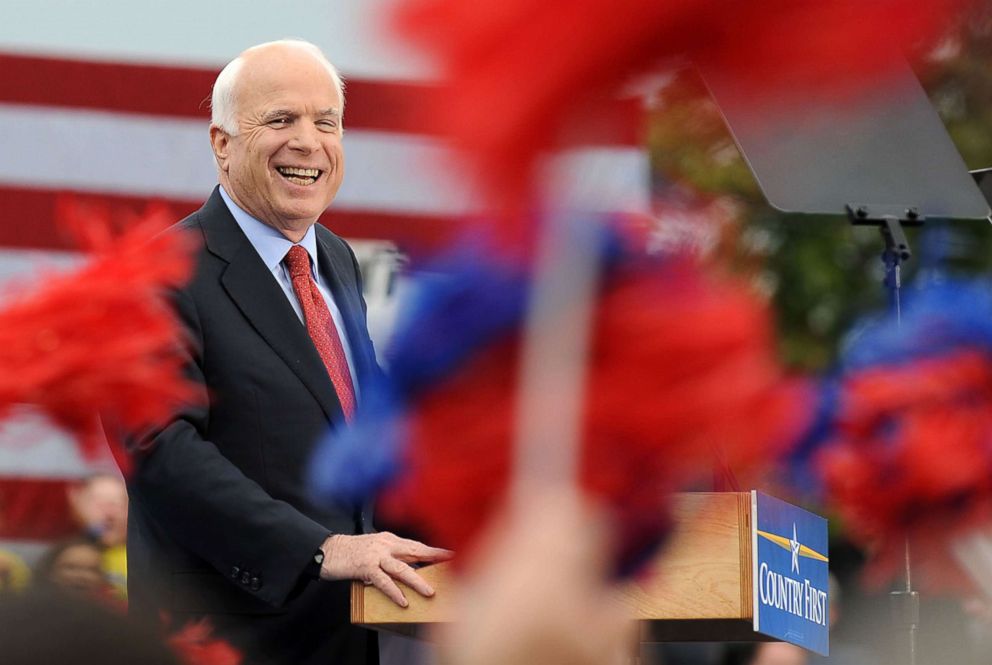

Days after the fall of Lehman, the Republican presidential candidate, Senator John McCain, would suspend his campaign because of the "historic crisis of our financial system," suggesting that Democratic Senator Barack Obama do the same thing before the Congress spin-offs in the financial sector.

Charles Ommanney / Getty Images

Charles Ommanney / Getty Images

True, the sudden collapse of a financial giant, a staple of business, was unthinkable just days before.

A week ago, Lehman Brothers was a 158-year-old institution employing 25,000 people. He survived two world wars and the Great Depression. Yet that morning the market spoke – this story counts for nothing if you can not pay your bills.

In an instant, billions of dollars of wealth were destroyed. Faded away.

Win McNamee / Getty Images

Win McNamee / Getty Images

I look up, scanning the iconic central headquarters of Lehman Brothers and its thousands of windows – through a few, I can see a sign saying "F — PAULSON", as in Hank, the US Treasury Secretary.

Over the weekend, hope persisted that Secretary Paulson – along with the Federal Reserve, Bank of America and Barclays – would reach an agreement to rescue Lehman Brothers. But it turns out that to the surprise of many, there will be no white knight to intervene.

A few months earlier, competitor Bear Stearns was spared a sale to JP Morgan, but for a price of $ 2 per share – an incredibly low number, everyone, including me, assumed an error. . In the following years, many, including Paulson, will debate whether Lehman could or should have been saved.

So we are here. For most of the past year, I attended as a journalist as the crisis worsened from a low-pitched roar to fears, panic, and the bloody rush of exits.

I've seen it outside of bankrupt companies, unemployment lines, closed factories and the frenzy of the New York Stock Exchange. And now, apart from one of the largest and most powerful financial institutions in the world, Lehman Brothers is no longer.

Nicholas Roberts / AFP / Getty Images

Nicholas Roberts / AFP / Getty Images

How did it happen? Greed? Too much risk taking? The collapse of the housing market?

Everyone was wondering: and my retirement savings? My bank account? What about my job? My house?

There is a constant rate of constant fear. Another sale More foreclosures. When will it end? And how, many ask, will I make the next payment on my mortgage – now bigger than the value of my house?

That's all in my mind, so I wonder: how did the smartest guys in the room do it, so badly?

Today, 10 years later, we can still debate what really put Lehman Brothers and so many other companies on their knees. The answer is complicated, messy and has supporters on all sides.

Spencer Platt / Getty Image

Spencer Platt / Getty Image

There was the repeal of Glass-Steagall in the late 1990s, which led to greater risk taking and less stringent standards in banks. The insatiable appetite of hedge funds and investors for more complex financial products related to mortgages, namely the dawn of mortgage-backed securities, secured debt securities and other products complex derivatives.

Acronyms like MBS, CDO and CLO popped up everywhere on Wall Street, on CVs, in conversations, but few could explain them completely. There was the fact that anyone wanted a mortgage – or five! – I could get it, and many did it.

The rise of subprime mortgages, thanks to mortgage brokers and policies to promote homeownership, has encouraged many people to spend money. And all that money, all this speculative capital poured into the purchase of homes and mortgages has all but disappeared when the real estate market has collapsed, causing chaos and devastation.

But whatever the underlying explanation, the reality is that many of the employees I saw this morning did not return to the financial sector; their jobs have disappeared with their employers and, in some cases, whole industries.

Source link