[ad_1]

Last year, when Popular Mechanics covered the future of cancer treatment, they stated that many of James P. Allison's contemporaries thought he would win the Nobel Prize. But to be honest, it was a euphemism. People admired him. His work was so brilliant that his name opened doors to other scientists. "Oh," would say very important people when they would discover that he had agreed to be interviewed for my story. "So you have the big guns on this one."

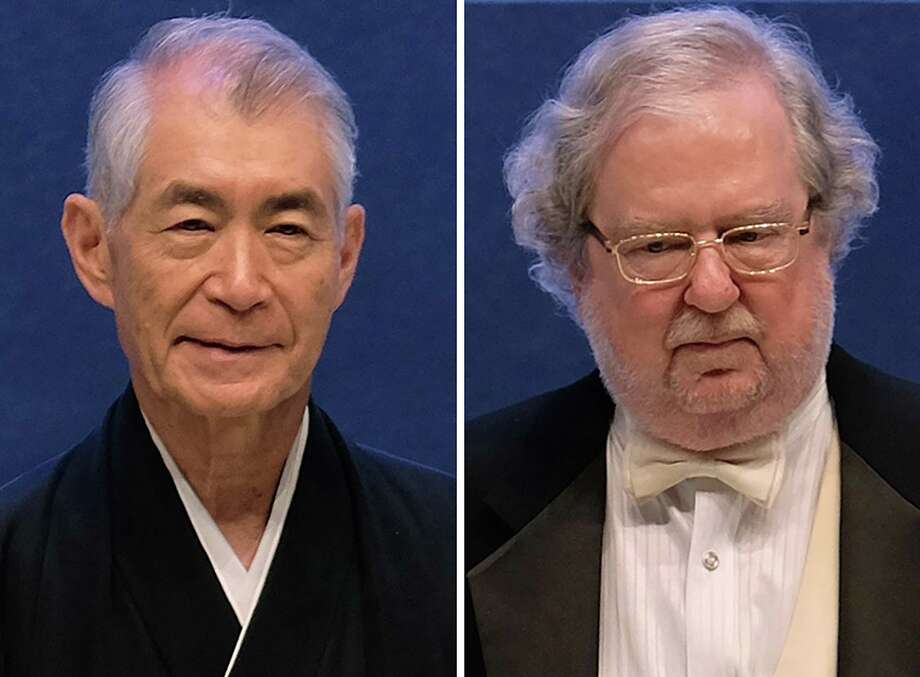

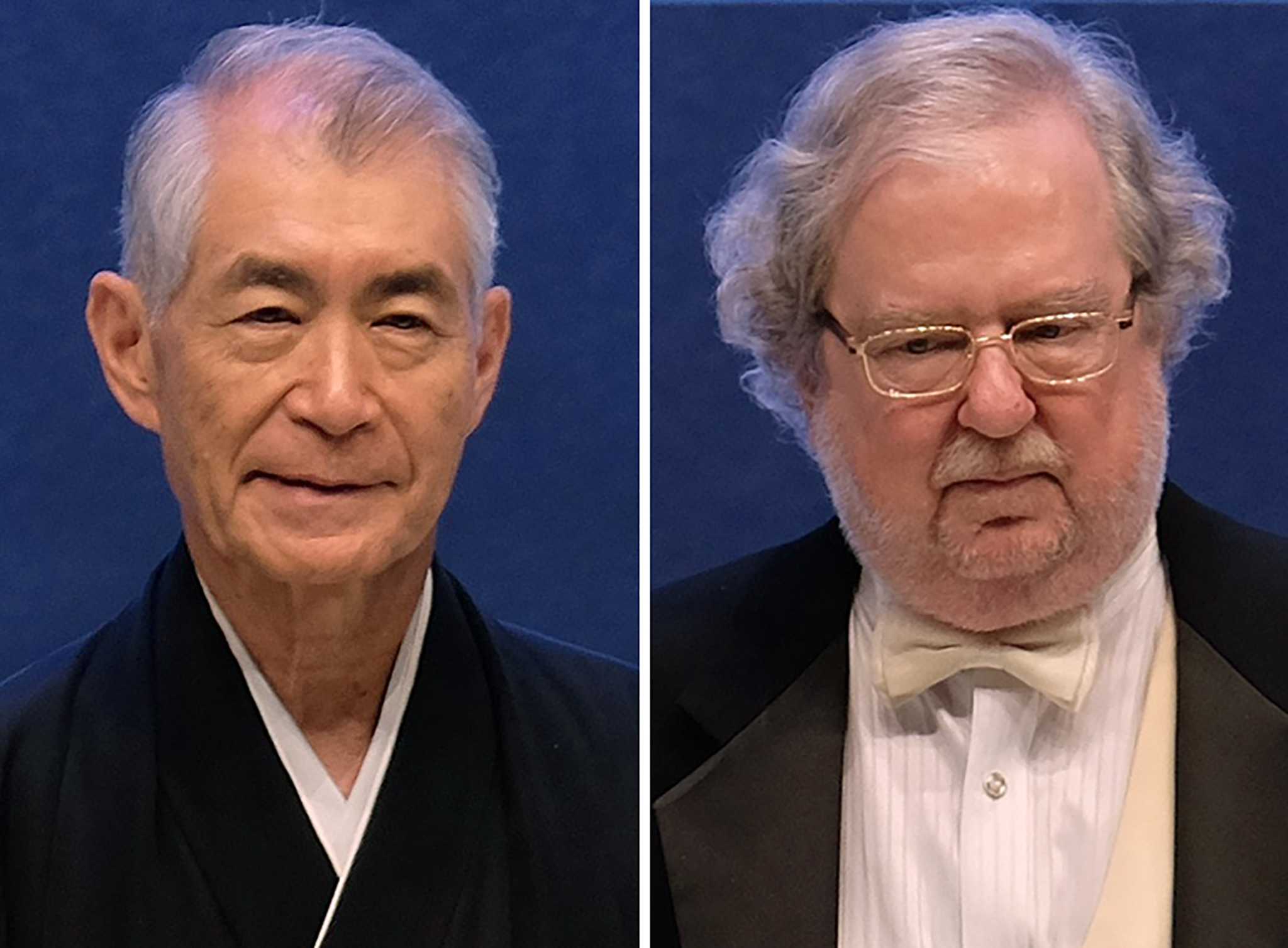

The prediction has proven judicious. On Monday, Allison, who heads the immunology department at the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Tasuku Honjo, a professor in the Department of Immunology and Genomic Medicine at the University of Michigan. Kyoto University, Japan. The two scientists independently discovered cellular cellular mechanisms that have become the foundation of immunotherapy, a new type of cancer treatment in which doctors convince the patient's immune system to attack tumor cells as if they were of a bacterium or a virus.

Here's how it works: The immune cells called T cells are devastating killers, attacking everything in the body and displaying molecules called antigens that identify it as alien and potentially threatening. We would be in trouble if the T cells went crazy and started attacking everything they could feel. The body has therefore put in place a system of checkpoints to prevent them from targeting healthy cells. Cancer, being a unique amalgam of and not-self, exploits this checkpoint system by claiming to be part of the body to escape the attention of the immune system.

Allison and Honjo have each discovered a way to close control points with drugs called "checkpoint inhibitors," which allow the patient's immune system to rediscover and then destroy cancer cells throughout the body. This is a brand new category of cancer treatment. Before Allison and Honjo's work, if you could not cure cancer through surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy, you could not do anything else. Today, drugs based on immunotherapy, such as Keytruda, Yervoy, Opdivo and Tecentriq, have prolonged the lives of hundreds of people with otherwise incurable cancers.

It was not an easy road. Even until the 2000s, the field of immunotherapy was not well regarded by other cancer scientists. Many considered that it was ridiculous, even dangerous, to try to transform the immune system against cancer.

"In 2006, I spoke at Cold Spring Harbor and I was the only immunologist to speak – the only immunologist to attend the conference," Allison said when Popular Mechanics recounted the original story . "It was scary. My friends who knew this area said You'd better be careful because these people hate immunotherapy. They will kill you. "

Obviously, they did not do it. Today, they could even offer him a glass of champagne.

Source link