[ad_1]

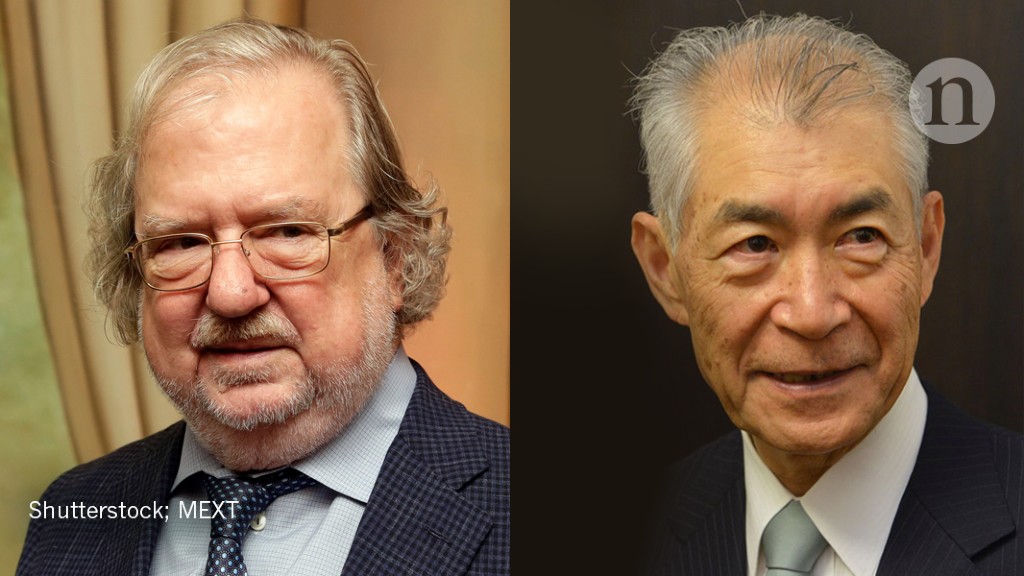

Two scientists who have come up with an entirely new method of treating cancer have won the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

James Allison of the MD Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas in Houston and Tasuku Honjo of Kyoto University in Japan will share the award of 9 million Swedish kronor (one million US dollars).

The pair showed how proteins on immune cells can be used to manipulate the immune system to attack cancer cells. Since then, this approach has led to the development of therapies that have been hailed as extending the survival of some people with cancer and have even eliminated all signs of disease in some people with advanced cancers. . Researchers have flocked to the approach and immunotherapy is now one of the most popular areas in cancer research.

Early excitement

Allison is in New York for a conference on immunology and was woken up at 5:30 pm by a call from her son who announced the good news. At 6:30 am, colleagues were knocking at the door of her hotel room with champagne for an impromptu party. The Nobel Committee did not reach him until some time later.

"That still has not completely understood me," Allison said at a press conference. "I was a basic scientist. Making my work really impact people is one of the best things I can think of. It's everyone's dream. "

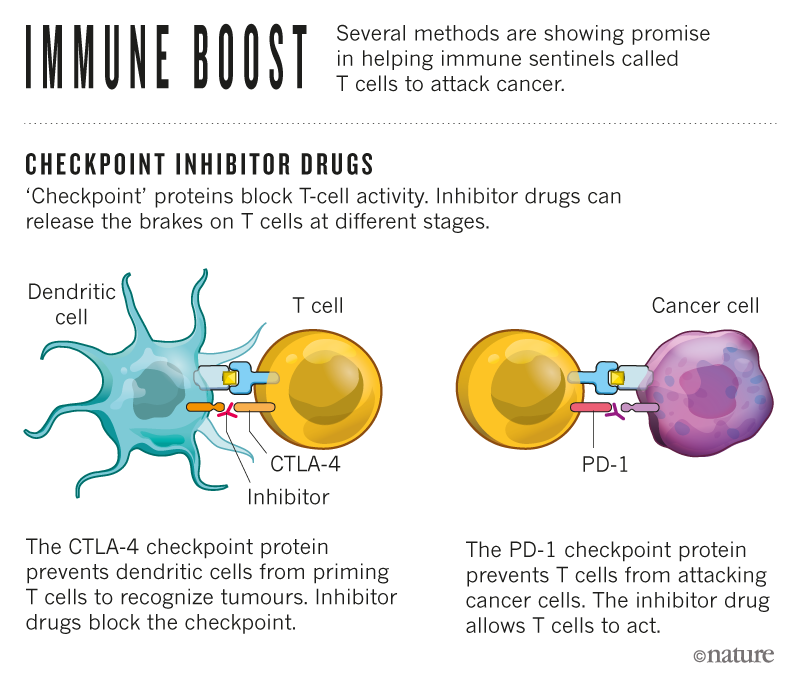

In the 1990s, Allison, then at the University of California at Berkeley, was one of the scientists who studied a protein called "checkpoint", the CTLA-4 protein, which blocks the immune cells called T-cells. , Allison and colleagues developed an antibody capable of binding to CTLA-4, eliminating the brakes on T cell activity and releasing them to attack cancer cells in mice. A clinical study conducted in 2010 showed that the antibody had a striking effect on people with advanced melanoma, a form of skin cancer.1.

Working independently of Allison, Honjo discovered in 1992 a different T cell protein, PD-1, which also acts as a brake on the immune system, but by a different mechanism. PD-1 has become a target in the treatment of cancer. In 2012, research on human subjects revealed that the protein was effective against several cancers, including lung cancer, a leading cause of death.2. The results were dramatic: some patients with metastatic cancer have begun a long-term remission, raising the possibility of a cure.

Release the brakes

"The discoveries of Allison and Honjo have added a new pillar to cancer treatment. This is a totally new principle because unlike previous strategies, it does not rely on cancer cells, but rather on the brakes – the control points – of the host immune system. Said Klas Kärre, a member of the Nobel Committee and Immunologist. Karolinska Institute in Stockholm who described the work of the laureates during the Nobel Prize announcement. "The major discoveries of the two winners represent a paradigm shift and a milestone in the fight against cancer."

In recent years, clinical work on drug-inhibiting CTLA-4 and PD-1 mechanisms, known as "immune checkpoint therapy" – has developed rapidly. Treatments that block PD-1 have been shown to be effective in lung and kidney cancer, lymphoma and melanoma. Recent clinical work combining combination therapies targeting CTLA-4 and PD-1 in patients with melanoma has shown that this approach may be even more effective than CTLA-4 alone.3. Trials are underway to evaluate the effectiveness of checkpoint therapy against most types of cancer, and scientists are testing many other checkpoint proteins to see if they could serve as targets.

But Allison and Honjo were not alone: others also made important early discoveries about checkpoint inhibitors, notes Gordon Freeman, immunologist at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, in Massachusetts, who was disappointed at not being recognized for his contributions. Freeman, along with immunologists Arlene Sharpe of Harvard Medical School in Boston and Lieping Chen of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, studied PD-1 and a molecule called PD-L1, which links to it .

The drug ipilimumab, an antibody that inhibits CTLA-4, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 and was the first control point inhibitor to reach patients. But Freeman points out that it has been shown that CTLA-4 inhibitors have only worked up to now in melanoma. And the FDA has approved drugs that target PD-1 and PD-L1 to treat 13 different cancers. "PD-1 and PD-L1 are what works for a very wide variety of people," he says. "And our discoveries were fundamental there."

However, Freeman claims that CTLA-4 led the way and that Allison played a key role in promoting the pitch. "Jim Allison has been a real advocate and advocate for the idea of immunotherapy," he says. "And CTLA-4 was a first success."

Obvious choices

The immunologist Jérôme Galon of INSERM in Paris, the French national agency for biomedical research, was not surprised by the committee's decision to award the prize to Honjo and Allison. "I think they really deserve it," he says. "You can always multiply and have a lot of other people, but these are the first two obvious choices."

He adds that the award reflects how much the immune approach to cancer has evolved. When PD-1 inhibitors demonstrated their effectiveness against lung cancer in 2012, the battlefield appeared. University and industry researchers then began to look for ways to increase the number of patients who can benefit from drugs. "Ten years ago, no one was interested – nobody except a few immunologists," says Galon. "It's such a big change."

In a 2013 interview with NatureAllison described the resistance he encountered when he tried to interest pharmaceutical companies. "It was very frustrating," he said. "They said," It can work in the mouse, but it will never work in humans. " The concept was new and so unusual. "

Allison walked from company to company in search of the one who would take over the project. In the end, Bristol-Myers Squibb, of New York, was the one who pushed the ipilimumab over the finish line. Since then, other pharmaceutical companies have developed checkpoint inhibitors whose use has been approved in humans.

Combined therapy

According to Mr. Galon, the main advantage of these drugs is to extend the lives of patients for several years rather than weeks or months. But only a fraction of patients experience such dramatic reactions, and researchers strive to increase them by combining checkpoint inhibitors with each other and with other treatments. "The huge advantage over other treatments is that patients experience long-term survival," he says. "Unfortunately, only a subgroup of patients responds."

Through all of this, it's exciting to see the ground grow, says Freeman. "It's really an incredible amount of creativity and human energy," he says. "It's wonderful because a lot of cancer patients are doing better."

In 2015, Allison won a prestigious Lasker Award for her work on cancer immunotherapy. In 2016, Honjo won the Kyoto Prize for Basic Science, a global prize awarded by the Inamori Foundation.

Source link