[ad_1]

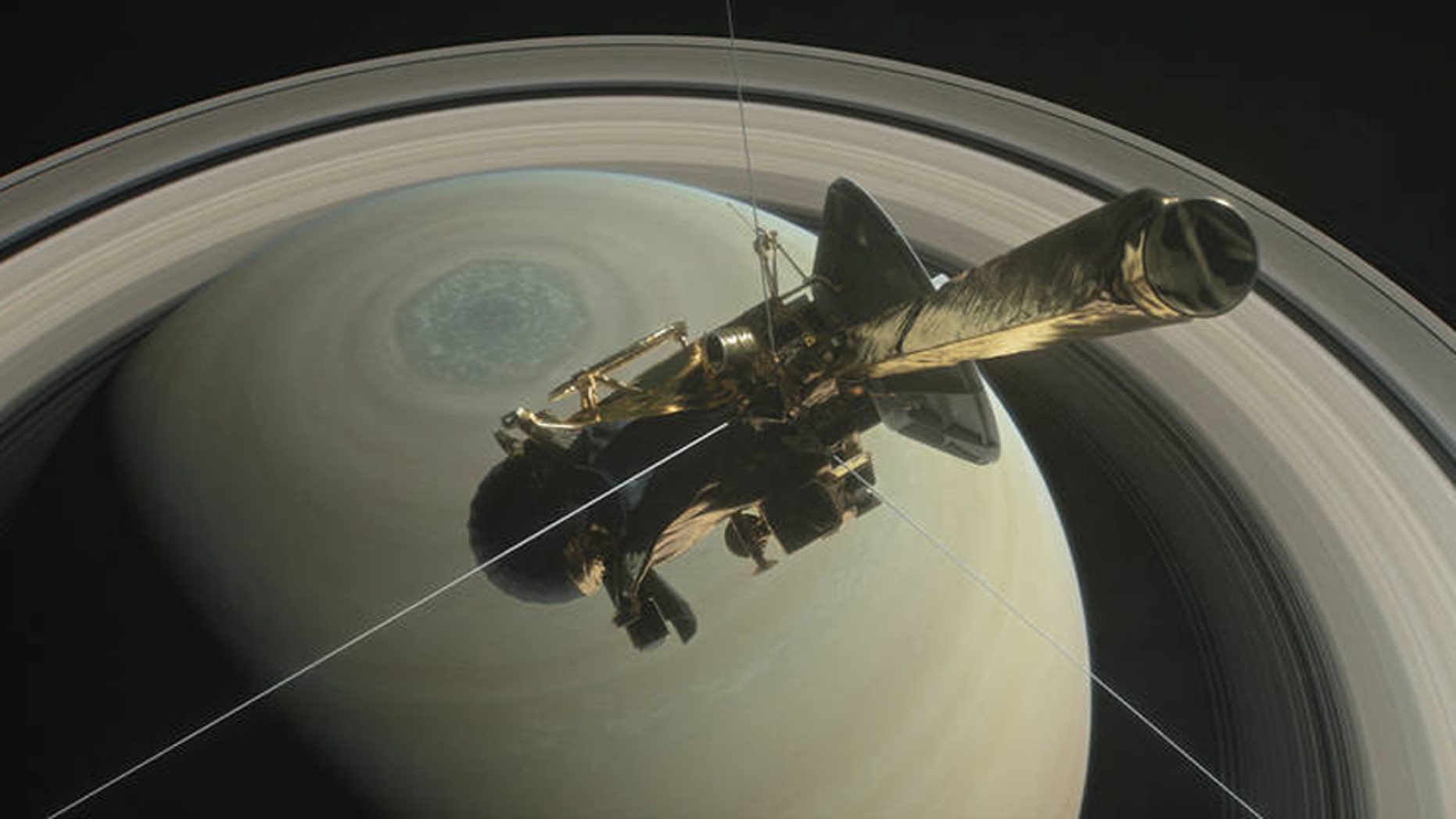

Artistic representation of NASA's Cassini spacecraft (Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech).

In the eyes of distant Earthling, the gap between Saturn and its rings seems calm, like a deep breath of empty space between a beautiful and complex structure. But in 11 new articles, which emerged from the disappearance of one of NASA's most valued missions in the field of planetary science, scientists have destroyed this illusion by presenting a set of unexpected phenomena and complex dancing through this void.

These articles, published today in two key scientific journals, constitute the first research to publish data from the "Grand Finale" of the Cassini mission, a daring series of orbits during which the spacecraft probe Is threaded between Saturn and its rings. Taken together, the newspapers describe in detail what is happening between the deepest rings on the planet and the upper atmosphere. Surprising and catchy phenomena, such as a hail of compounds hammering the equatorial region of the planet and an electric current produced solely by the winds of the magnetic field planet.

"We really thought of it as a loophole," Linda Spilker, NASA's Cassini mission project scientist, told Space Space.com about the area between Saturn and its rings. The team was optimistic about what Cassini could learn when she disappeared, but the operation finally resulted in what she called "a much richer scientific return than we had imagined" – she went to to compare that to a whole new mission. [Amazing Saturn Photos from NASA’s Cassini Orbiter]

The Cassini spacecraft spent 13 years studying Saturn and its moons. But while the engine was running out of fuel, the mission scientists devised a bold trajectory that would loop the spacecraft through the rings of Saturn before it burned in its atmosphere. This destruction prevented the potentially habitable moons of the system from catching the Earth's germs that may have clung to the spacecraft.

But it also allowed scientists to extract a little more data from its instruments – and pushed the spacecraft further than they thought possible, since neither Cassini nor his instruments did been designed to accomplish such an incredible feat. The scientists gathered for the first dive, wondering if the spacecraft would survive long enough to even begin the grand finale.

Spilker and other scientists at Saturn believe that the revelations of the probe extracted from the data are far from complete, even after the documents released today (October 4). "You are basically looking at the sources of data that Cassini has received over the past 13 years, and in fact we have spared only cream," Spilker said. This work helped scientists begin to understand the individual phenomena taking place at Saturn. "The next step that is still happening now is to take these elements and bring them together in a consistent picture in order to look at the whole set of data and ask if there is a common story" said Spilker.

But in the meantime, here's a glimpse of what scientists have already learned about the ring planet.

It's raining, it's raining

A new discovery was brought about by the results of such strange instruments that scientists in the team and beyond initially thought there must be a mistake. This instrument, called the ion and neutral mass spectrometer, or INMS, can detect the chemical composition of the captured material.

Scientists are particularly excited to see these results because it had been learned that the instrument was on something. "Since the end of the mission, we have talked a lot about these INMS results," said Bonnie Meinke, a Saturn scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, who had not taken part in any of the new research . "At first glance, that's the kind of thing you almost do not believe in, and as a scientist, you have to do a little gut check," Meinke said.

The instrument had proven itself, having collected critical data earlier in the mission while Cassini was exploring moons such as Titan and Enceladus. "Then we really have to focus on Saturn and let it play the star role for the last part of the mission," said Rebecca Perryman, operations manager for INMS at the Southwest Research Institute at Space.com. "We did everything we could to make sure everything was planned in the first place and we were really impressed that INMS would be able to get fantastic results once we started diving into the atmosphere." [In Photos: Cassini Mission Ends with Epic Dive into Saturn]

They had expected these results to measure the masses of "rain ring", which scientists saw as a trickle of tiny particles falling from Saturn's innermost ring. towards the upper atmosphere of the planet – mainly hydrogen and helium – nothing extraordinary.

But what they seem to have found was much larger than expected, coming from much more exotic compounds. The instrument spotted not only hydrogen and helium, but also carbon monoxide, methane, nitrogen and unidentifiable remains of organic molecules.

Other instruments have suggested that this downpour also included ice particles of water and silicate and showed that the shower was triggered by the interaction of these particles with the highest levels from the atmosphere of Saturn. Around the ring structure, this amounts to about 10 tons (9,000 kilograms) per second.

"The complexity of what was going on there and the amount of material collected was very surprising," said Hunter Waite, lead INMS investigator and scientist at the Southwest Research Institute at Space.com. And the discovery does not just reveal an intriguing phenomenon about a distant world – scientists say that if the discovery holds, it could have far deeper implications in our own solar system and beyond.

Waite said the unexpected diversity of compounds in the ring rain could affect estimates of the composition of the atmosphere by scientists, which would eventually involve adapting assumptions about the formation and the evolution of Saturn and its neighbors. "It may well be that facade is," says Waite about Saturn. "[That might have] been a little misleading in the direction of our thinking about training and evolution. "

Moreover, as there is so much material, the new results pose a headache: where does it come from? "It can not be a continuous process, otherwise the rings would not be there," Meinke said. They would lack material in maybe tens of thousands of years, leaving Saturn bare. "The real story that [the paper is] Telling, it's about the rolling of the rings of Saturn … The rings can last a long time as they move and turn around constantly. "

The magnetic call of a planet

Cassini was also equipped to measure the magnetic field of Saturn. Although scientists have studied the magnetic field before, they could only do so briefly on overflights like those of Pioneer and Voyager, and Cassini's grand final plunged them deeper than ever into this field.

And the measurements gathered during these tight curls offered their own surprises. Scientists already knew that the magnetic field of Saturn seemed perfectly aligned with the axis on which it turns, which is a challenge because, as far as we can make it account, the magnetic fields are by definition created by crossing the spins. [Cassini’s Greatest Hits: The Spacecraft’s Best Images of Saturn]

But a new analysis of the measurements of the grand finale shows that these two phenomena align even more perfectly than the scientists had predicted. This means that scientists must return to the board, trying to convince a response from gravity data and magnetic fields. "We know there's something weird about," Michele Dougherty, a physicist at Imperial College London and lead author of the newspaper, told Space.com.

She and her colleagues think that there may be something that is blocking scientists' views on the true magnetic heart of Saturn, creating the illusion of almost perfect alignment and thwarting their theories. "We have not yet received an answer, but whatever response is proposed, it will actually change people's understanding of the inner structure of planets," Dougherty said.

As long as they do not understand what is happening, scientists will not be able to accurately measure the time it takes Saturn to turn. "It's a little embarrassing, we're in orbit there for 13 years and we still can not tell how much time is left in Saturn," said Dougherty. Without fixed characteristics on a solid surface or magnetic field to follow, they are blocked with an estimate of 10.7 hours.

Hunting in the heart of the magnetic field has been partially blurred by another surprise hidden in the magnetic data: a new phenomenon produced by this magnetic field interacting with bands of winds moving at different speeds in the upper atmosphere of Saturn – a current electric waving through a layer of atmosphere called the thermosphere.

Here's how it works: Saturn is wrapped in wind bands, that of the equator moving the fastest and those of the north and south moving more slowly. When a loop-shaped magnetic field structure aligns so that one end lies in this equatorial band and the other one does not, the equatorial wind pulls the charged plasma particles that surround it, which in turn directs the magnetic field line.

The result measured by Cassini is an electric current as powerful as 20 large combined terrestrial power plants. As a side effect, this current also produces heat in the surrounding atmosphere, which can help explain a long-standing mystery about Saturn. "One of the enigmas of Saturn's thermosphere is that it's hotter than expected," Krishan Khurana, a magnetosphere scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles, told Space.com and the lead author of the article. "That provides part of the answer."

And while Saturn is the star here, the results can also explain a second mystery of the solar system. "The atmosphere of Jupiter is very turbulent and the same phenomenon applied to Jupiter's magnetic field would create quite large currents and warm up the thermosphere quite quickly," said Khurana. That includes the big red blot, the giant storm that infamous, gnarls the southern hemisphere of Jupiter, and that the scientists realized is terribly grilled. [Wave at Saturn: Images from NASA’s Cosmic Photo Bomb by Cassini Probe]

The grand finale is not the end

This is just a sample of the research published today – which is actually just the beginning of the scientific flow that the Cassini Grand Final will produce in the future. An article focuses on the atmosphere of Saturn that produces radio auroral emissions to try to understand how these radio waves are produced.

In another article, a team of researchers has identified a long-awaited but unknown radiation belt that extends from the planet's upper atmosphere to its innermost ring. This means that it is completely distinct from the main magnetosphere of Saturn, by trapping charged particles in this space between the upper atmosphere and the inner ring. Further study of this new radiation belt shows that because of the interference of large rings, this radiation belt is quite weak compared to other structures of this type.

A different instrument aboard Cassini measured the electron density in the Saturn ionosphere, mapping two separate layers. The lower layer includes larger, neutral molecules and charged around the equator, under the rings and their flow of material; the upper layer has a much smaller number of tiny charged particles.

And this same INMS instrument, which made it possible to identify as many strange compounds in the so-called annular rain, also allowed scientists to calculate the approximate temperatures of the thermosphere layer of the atmosphere traversed by Cassini. These measurements ranged from 67 to 97 degrees Celsius (150 to 200 degrees Fahrenheit).

Two other articles that were not yet ready for publication highlight topics such as the tiny moonlets embedded in Saturn's rings and the gravity measurements made on the giant planet. And then, of course, there are many more discoveries to be made as scientists continue to delve into and analyze the data from the Grand Final and the rest of Cassini's work – not to mention the sightings of any successor spacecraft inspired by the discoveries of the mission.

"I think it's a really exciting time," said Meinke, the Saturn scientist who is not affiliated with any new research. "After 13 years of Cassini data, this latest news was really exciting, which made us want to go back and teach us a lot more than we thought we could learn."

Original article on Space.com.

Source link