[ad_1]

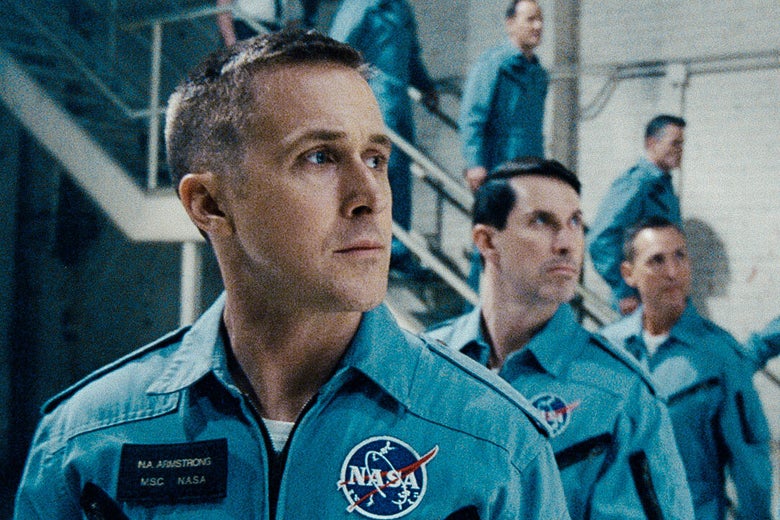

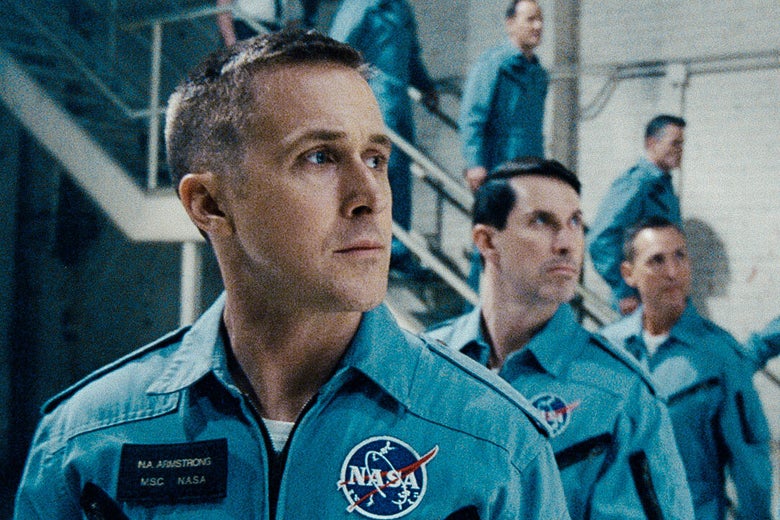

Ryan Gosling in First man.

Universal Pictures / DreamWorks

In the epic 1983 space flight of Philip Kaufman The good stuffAir Force pilot Chuck Yeager (Sam Shepard) breaks the wall of sound, mocks the passivity and containment of astronauts recruited for NASA's nascent space program: "Anyone who gets into this damn case will spam in a box. Damien Chazelle & # 39; s First man, a narrowly centered portrait of Neil Armstrong based on James R. Hansen's pioneering moonwalker biography, spends the entire two hours and twenty minutes vigorously refuting the statement that the first men to have slipped the terrible links of the Earth were little more than conscious lunch meat. The opening sequence of an almost cloying intensity locks us into a cockpit with Armstrong (Ryan Gosling) while he barely manages to land an X-15 aircraft powered by a rocket that has accidentally bounced back from the atmosphere and flew away, in the manner of Icarus, too close to that of the planet. outermost edge.

The exhilarating and yet disturbing sensation of this first scene – a sensation almost analogous to that felt on the gravitron fairground attraction – will come back at intervals all the way through. First man. After recruiting Armstrong for the space program, he volunteered to be the first to test an elaborate gimbal mechanism designed to recreate the multidirectional movement of gravity-free flight. Although his first lap in the machine made him lose consciousness, Neil barely regained consciousness before saying, "We're going back." "Can not we?" The dazed audience may be excused for thinking, but we returns there, with Chazelle camera taking us on a vertiginous turn without mercy.

Such as it is interpreted by an unusually stuffed Gosling, Armstrong is a brave man, but his courage does not manifest as a cowboy boaster, but as an obsessive fixation on the verge of achievement. ;impossible. "I see the moon and moon sees me," he says in a lullaby to his 2-year-old daughter in an early stage. Later, dancing in the kitchen with his wife, Janet (Claire Foy), he plays an easy-to-listen Space Age song – full of thérines and harmonizing choirs – entitled "Lunar Rhapsody". And when tragedy hits some of his astronaut comrades. at the training – in 1967, three of NASA's top astronauts died when the Apollo 1 command module caught fire during a rehearsal launch – Neil left the day before early to to look in the air before the rock, an inaccessible stone, for which he is now more determined than ever. achieve.

No matter how horrible, the Apollo 1 incident is not even the main personal loss that drives Neil's lunar obsession. His daughter dies shortly after he has finished singing this lullaby, the victim of an inoperable brain tumor. His two remaining sons need him more than ever, but Neil, an emotionally averse man in mid-century classic fashion, burrows into his job at NASA and leaves the job of keeping the family together, at his woman more and more furious. Unlike many of the countless movie wives to whom such work has been imposed, Janet sees exactly what is happening and calls her husband. When the Apollo 11 is finally ready to take a crew to the moon in 1969, she insists that he be the one to sit with their boys and tell them there is a chance he will not come back. He obeys but communicates to the frightening news the invincible freshness of a general at a staff meeting: "We have every confidence in this mission."

Chazelle, like his hero, sometimes seems to just wait until he can return to one of these claustrophobic space modules and feel gravity slip a way.

First manThe screenplay was adapted from Hansen's biography by Josh Singer, who also participated in the scenarios of the two Projector and The post office. These talkative and well-populated films found themselves in their historical moment in a much more intimate and unfamiliar way First man do not do it. Although this is happening between 1961 and 1969, the social upheaval of those years is almost invisible from the screen. From the beginning, we see an excerpt from President John F. Kennedy's televised speech promising a landing on the moon in the next decade. Much later, while the Apollo 11 mission is about to begin, there is an awkwardly overlapping montage – similar, in fact, to a middle one. The post office-That juxtaposes "Whitey on the Moon" in the proto-rap of Gil Scott-Heron with clips of dissidents, including Kurt Vonnegut, who oppose the cost of the space program. What this brief glimpse of the outside world was supposed to add to the film is not clear: do Vonnegut and Scott-Heron make sense or not? What would Neil have to say about their arguments against space exploration? In a film that is usually so linked to her hero's point of view – never before has a space epic been presented with so many close-ups – it is odd that the camera suddenly pulls out to reveal a larger social landscape. , then zooms out without our understanding why.

Corey Stoll plays Buzz Aldrin, the second man to walk on the moon and the one who, in almost 50 years since the landing, has become the public face most associated with this historic event. Among the few scenes we have with him, it is clear that Buzz is Neil's characteristically opposite: a cut, a blunt talker, a hen's head. But Gosling and Stoll never have a chance to explore the implicit friction between their characters. In fact, apart from the tense but loving relationship between Janet and Neil (impeccably acted on both sides), First man does not show much interest in Neil's social world. Chazelle, like his hero, sometimes seems to just wait until he can return to one of these claustrophobic space modules and feel the gravity disappear.

Kyle Chandler, Jason Clarke, Pablo Schreiber and Shea Whigham play all roles of Armstrong's colleagues at NASA, but (with the exception of a few brief scenes with Clarke), they seldom stand out in relief. It's in the training and spaceflight scenes – especially towards the end, when Armstrong and Aldrin finally cross the air and embark on this well-researched, but still exciting, return trip to the lunar surface. – than First man really, well, take off. Chazelle – whose last two films were the shredded drama Whiplash and the faded musical La La Land–is a director specializing in sensations and intensity. His feat in flying scenes, aided by the portable camera of cinematographer Linus Sandgren and the sound design of Mary Ellis, is to place the viewer in the cockpit with the astronauts, hammered by noise, light, movement and the G force, but still loaded with making complex calculations and decisions in a split second.

The flight scenes are so stressful and sensory that when Neil's boot finally arrives on the surface of the moon – the sand, he says at the control of the mission, is much thinner than it is. imagined, almost like powder – the total silence on the soundtrack is the welcome respite. After all the tension and conflict needed to get there, the moonless expanse of the moon is both a relief and, in a way difficult to define, a disappointment. But the golden hue of the frontal plates on the astronauts' helmets makes this moment as emotionally impenetrable – when Neil finally utters the line heard all over the world, "It's a small step for the man, a big one. not for the man, "Gosling's face is obscured. It is an appropriate choice for a film as fascinated by the distant interior landscape of its hero as by the unexplored surface of the moon.

Source link