[ad_1]

-

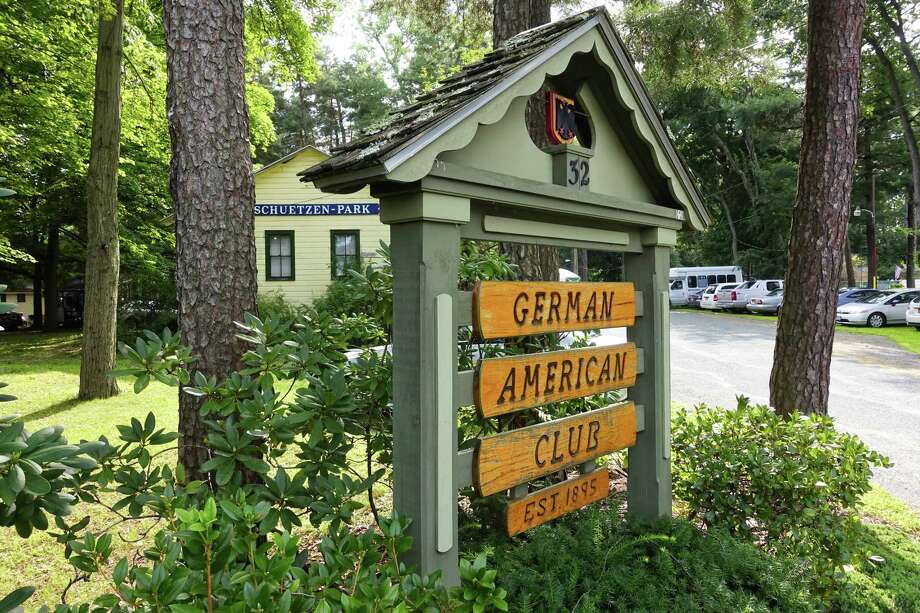

A view of the German-American Club of Albany on Sunday, August 19, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

A view of the German-American Club of Albany on Sunday, August 19, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

Photo: Paul Buckowski

A view of the German-American Club of Albany on Sunday, August 19, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

A view of the German-American Club of Albany on Sunday, August 19, 2018, in Albany, N.Y. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

Photo: Paul Buckowski

ALBANY – One hundred years ago, the South End and Central Avenue. German ranks throughout the country and runs off the press on the pages of half a dozen newspapers. Singing clubs in the community, bands roused residents on Madison Avenue and parades celebrated "German Day."

Albany's first German arrived in the 1660s. By 1854, Germans made up half of all immigrants to the U.S., with many flooding from New York City's docks up the Hudson River to the Capital Region. There were 12,119 German-born residents in the Albany-Schenectady-Troy metro area at the population's peak, according to the census. As the next generation was born on American soil, the community began to blend in.

Then World War I broke out in Europe. President Woodrow Wilson criticized Germans in the US as "hyphenated Americans" who could turn on the nation. In early 1917, the Albany Federation of German Catholic Societies, representing 1,500 German-Americans, sent a telegram to the president declaring loyalty to their adopted country.

But two months later, when the U.S. declared war on Germany, not even pledges to the president could stop discrimination as anti-immigrant war hysteria spread. Some German-Americans tried to prove themselves with patriotism: the German Gun Club allowed the Albany Defense Corps to practice its rifle range and German churches in Albany donated tens of thousands of dollars to buy bonds that supported the war effort.

But more Germans simply thing to lose their identity.

"It seems that with a lot of intolerance that was shown against German-Americans, that was enough to have the remaining Germans just assimilated and blended in," said Christopher White, the leading scholar on Germans in Albany. "It was so much easier than you would have thought it would be very difficult to win because of the country you're living in, the country that's supposed to be your homeland, is at war with your trainer homeland. "

One hundred years after the end of the "war to end all wars," White's research and Times Union archives together re-trace what happened to Albany's German-Americans who disappeared.

The day after the U.S. entered WWI in April 1917, Albany officiated at a census of German "alien enemies" – males 14 years or older. They found 300 to 400 living in the city.

Albany's police commanded German aliens to surrender their weapons. The first man who did so, handing over 17 rounds and double-barreled shotgun that he used to kill rats on his farm, said he was happy to obey the order.

The federal government required German "alien enemies" to register at their local police headquarters or face arrest, fines, imprisonment or possible deportation. Albany city officials also ask that Germans inform police if they intend to move from their city or city. By June 1918, 213 German aliens had registered.

German language studies were dropped from the Albany High School curriculum by popular vote of the students. Federal authorities seized the protocol book of Maennerchor, one of many popular German singing clubs.

U.S. government agents combed every inch of Albany County in search of "dodgers," "slackers," "spies" and "traitors" who had evaded the draft or were German sympathizers. Arrests of German-Americans spiked under the Sedition Act, enacted in May 1918.

Photo: Courtesy Of Library Of Congress / Chicago Daily News / Chicago History Museum Via Wikimedia Commons

Group portrait of a group of children standing in front of an anti-German sign posted in the Edison Park Community area of Chicago, Illinois in 1917.

Group portrait of a group of children standing in front of …

Tiber Menz was detained for the purpose of making war effort.

15-year-old Herman Wunsch was arrested for traveling outside the city. He was detained in one of four internment camps that imprisoned as many as 6,000 German-Americans during the war.

A landlady turned over, Frederick Schmidtbauer, for allegedly saying "America has no business being in this war, Germany is going to win the war, to hell with President Wilson." Schmidtbauer was unaccompanied and sentenced to two years in federal prison. Federal authorities said they believed they were unearthed at "hen's nest".

In September, a large box with the ends broken at the American Express office at Union Station in Albany with a 1916 Fatherland calendar written in German. The U.S. Justice Department inspected the box and found photos of the German king, military and maps. The intended recipient of the package, Maurice Maerclin of Delaware Ave., said it was sent to him by his brother in Chicago.

After the war ended on Nov. 11, 1918, the restrictions against Germans were eased. The Sedition Act was repealed. Internment camps were emptied. Goal German assimilation into the mainstream in the Capital Region was irreversible.

German-Americans moved outside Albany to Bethlehem and Delmar. The community's two major churches on Central Ave., Our Lady of Angels Catholic Church and St. John's Lutheran Church, no longer hold services in German. Albany's last German language newspaper folded in 1919.

By 1930, the number of German-born residents in the Capital Region had dropped to just over 8,100. By 1950, it has been increased to half of that amount. As of the most recent count in 2014, there were just under 3,000 German-born Capital Region residents.

The remaining vestige of the pre-WWI community is the German-American Club of Albany, founded in 1895. President Jim Reid said the club currently has 145 members, but only 20 percent claim German heritage.

When local scholar Christopher White asked some older members of the club who immigrated from Germany why they did not speak German together, they responded: "We're American now."