[ad_1]

Analysts, including former Boeing flight control experts, are concerned that a new automated flight control system on the Boeing 737 MAX is faulty and that it has altered the handling of the aircraft could have confused the flight deck of Lion Air Flight JT610.

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) announced Wednesday that it plans to ask Boeing to remedy a possible design defect in a new automated flight control system introduced for the 737 MAX.

He is also interested in the relevance of technical data and training provided to pilots who are moving to the new jet model. Flight control experts believe that the lack of information on the new system has likely baffled pilots flying the Lion Air plane that crashed on Oct. 29 in Indonesia, killing the 189 people in edge.

The aviation safety agency said Wednesday that "the FAA and Boeing continue to assess the need for software and / or other aircraft design changes, including operational procedures and training."

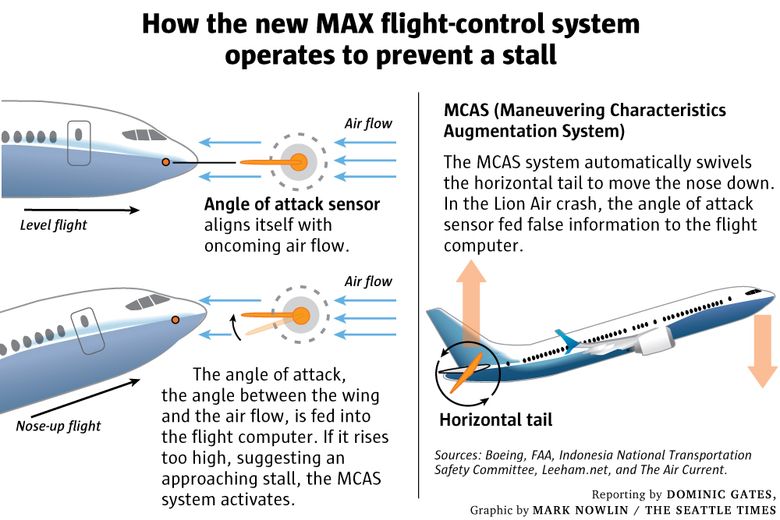

The investigation into the accident has already established that false readings of a sensor measuring the angle of attack of the aircraft (AOA) – the angle between the wing and the imminent airflow – could have unleashed a new flight control system on the MAX that was pushing the aircraft's nose continuously down.

FAA spokesman Greg Martin said that "the values of the attack angle used by several systems, including aerial data, combat commands, the stall warning , etc., the security analysis of each of these systems are being reviewed. "

Flight control experts say that the entry into service of the new system would have changed the aircraft's sense of control over what the pilots had experienced in simulator training, potentially confusing the aircraft on board. JT610 flight.

Boeing insists that the plane is safe to fly. Dennis Muilenburg, chief executive of Fox Business Network, said on Tuesday that Boeing was providing "all the information needed to fly our planes safely," said Tuesday the general manager of the Fox Business Network.

Even the pilots of American Airlines and Southwest, who expressed Monday their concern about not having received advance information on the new flight control system, continue to fly the plane. They were assured that a standard procedure put forth by Boeing after the Lion Air crash would shut down the system if it turned out badly in the future and would quickly bring the jet back into normal flight.

Even though it may not be part of the events that led to the Lion Air disaster, the new MAX flight control system is hotly debated.

Three former Boeing flight control experts were surprised by the FAA's description last week of the new MAX system. In an airworthiness directive, the FAA cited a Boeing analysis that "if the flight control system receives an erroneous input from an incorrect angle of attack sensor (AOA), there is a risk of recurring trim compensation commands "that will rotate the aircraft's horizontal tail to tilt the nose down.

The fact that the nose of the aircraft could be lowered automatically and repeatedly due to a false signal shocked Peter Lemme, a former flight control engineer from Boeing, who said that it looked like a design flaw .

"Considering controlling the nose (the horizontal tail to project the jet) is clearly a major concern. The fact of being triggered by something as small as a sensor error is staggering, "said Lemme. "That means someone did not do their job, there will be hell to pay for it."

Similarly, Dwight Schaeffer, a former electronics engineer at Boeing and senior director who oversaw the development of the systems, including the 737 stall management computer, stated that the brief description contained in the FAA Airworthiness Directive "Bluff me".

"Usually, you never have a single fault that could put you in danger," Schaeffer said. "I have never seen such a system."

A former vice president of Boeing, an avionics engineer – who asked for anonymity, said he feared being sued by the company for public criticism – also said he was surprised by the suggestion of the FAA: a single point of failure "that could bring down an airplane.

But he added that he would not necessarily call it a design flaw in itself, provided that flight crews have the ability to recognize what is happening and to be trained to deal with it.

However, that too is a point of controversy.

Boeing issued a newsletter last week to inform pilots around the world of the new flight control system and how to turn it off if it was not working properly. But the crew of Lion Air did not have this information and may have been confused by a difference in essential treatment that the system could have caused during the flight.

New flight controls

Bjorn Ferhm, a former fighter jet pilot and aeronautical engineer, analyst at Leeham.net, said the technical description of the new flight control system of the 737 MAX – called MCAS (feature augmentation system) maneuver) – that Boeing has released to airlines Last weekend, it was made clear that it is designed to intervene only in extreme situations, when the plane makes sharp turns that strongly solicit the cell or when it is flying at such a low speed that it is about to stall.

Southwest Airlines management told its pilots that Boeing did not include any description of the MCAS in the flight manual, as a pilot "should never see the operation of the MCAS" in normal flight.

But in extreme cases where it is activated, when the angle of attack reaches a range of 10 to 12 degrees, the system rotates the tail horizontally to lower the nose. And if the high attack angle persists, the system repeats the command every 10 seconds.

Ferhm said that Boeing must have added this system to the MAX, because when the angle of attack is high, this model is less stable compared to previous versions of 737. This is because the MAX has larger and heavier engines that are also cantilevered on the wing to provide more ground clearance. This changes the center of gravity.

The dreaded scenario in the Lion Air case is that the AOA sensor sent out false signals that cheated the computer into believing that the plane was in a dangerous stall position, causing the triggering the MCAS.

What happened next is crucial.

Any natural reaction of the pilot when the nose of an aircraft begins to bow without control is to pull the yoke and lift the nose. In normal flight mode, this would work, because pulling on the fork triggers switches that prevent any automatic movement of the tail tending to lower the nose of the aircraft.

But with activated MCAS, says Ferhm, these switches would not work. MCAS assumes that the yoke is already aggressively withdrawn and that it will not allow an additional withdrawal to counteract its action, which is to keep the nose down.

Fehrm's analysis is confirmed by the instructions that Boeing sent to pilots last weekend. The bulletin sent to American Airlines pilots points out that the removal of the control column will not stop the action.

Ferhm said the Lion Air pilots would have trained on 737 simulators and would have learned, over many years of experience, that pulling on the yoke prevents any automatic tail maneuver from pushing the nose down.

"It fits your memory," Fehrm said about this physical way of learning. But on the Lion Air flight, if the MCAS was activated because of a faulty sensor, the pilots had folded back and found that the nose down motion did not stop.

Fehrm is convinced that this led to a confusion in the cockpit that contributed to the loss of control. There is a standard procedure to disable any automatic pitch control, but somehow the drivers did not recognize that this was happening.

"MCAS had the wrong information and they responded to that," he said. "MCAS is to blame."

However, he warns that there is still not enough information to know that the single AOA sensor failure has triggered everything that happened and that the entire sequence of events that led to the disaster will not be clear before the end of the investigation. "It may not be as simple as a single sensor," he said.

Deep inside Boeing

In the meantime, Fehrm said that the worldwide pilots' notification about the MCAS and the reaffirmation of the procedure to be followed in case of a problem with the nose make that the MAX is now perfectly safe to fly.

"Boeing is right. If you follow this exercise, everything is fine, "he said. "Pilots will press break switches faster than you can blink."

In Seattle this week, approximately 400 aviation professionals from around the world gathered for the annual International Flight Safety Summit hosted annually by the Flight Safety Foundation (FSF).

When the FSF board chair, John Hamilton, vice president of engineering at Boeing Commercial Airplanes and former chief project engineer for the 737, delivered an opening speech on Monday, he recalled his own experience of the deep fear of a plane crash and used it to emphasize how Boeing people react.

Hamilton's wife is an Alaska Airlines flight attendant who, on January 31, 2000, was flying from Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. When Hamilton heard that Flight 261 from that city to Seattle crashed, fearing that she would be among the 88 dead. He later discovered that she was on a different flight.

But after his personal relief, he said he saw how this crash had reverberated in Seattle and the aviation community.

"What we do every day counts. Our work touches so many lives, "said Hamilton. "Everyone in Boeing … is deeply saddened by the loss of Lion Air flight 610."

He recalled that when he ran the 737 program at the head of engineering, "I was the sole responsible for the safety of this product," he said. "Every decision I made, I had to think carefully and deliberately, because many lives depend on this result."

He said Boeing, in collaboration with security officials, would investigate the Lion Air crash and "will learn what we can do to make sure it does not happen again."

Source link