[ad_1]

<! –

->

Astronomers recognize eight major planets in our solar system, with 200 orbits in orbit known to date. Much later, they discovered nearly 4,000 exoplanets in orbit around other stars, but to date, no exomoon has been found conclusively, despite some previous possibilities. On Wednesday, however – October 3, 2018 – astronomers announced new evidence of what could be the first true discovery of an exomoon. It seems that the planet Kepler-1625b is orbiting 8,000 light-years away, in the direction of the constellation Cygnus the Swan, in the west of October evenings.

Astronomers David Kipping and Alex Teachey, both from Columbia University, used data from Kepler probe, a planet hunter, and the Hubble Space Telescope, to discover the possible exomoon. It's a saga that has unfolded for these astronomers for several years, and the final results are not yet known … but the new proof is enticing. If an exomoon actually turns around Kepler-1625b, Kipping says:

The nearest analog would capture Neptune and place him around Jupiter.

If this can be confirmed, this first known exomoon also presents an enigma to astronomers. Such great moons do not exist in our own solar system. This discovery could force the experts to reconsider their theories on the formation of moons around planets. Thomas Zurbuchen at NASA's headquarters in Washington, DC, said:

If confirmed, this discovery could completely disrupt our understanding of how moons are formed and what they can be made for.

The scientific study of a possible exomoon for Kepler-1625b was published Wednesday in the peer-reviewed journal Progress of science.

Just as most of the planets outside our solar system have never been seen directly, we do not have a direct image of this possible exomoon.

"It was certainly a shocking moment to see this Hubble light curve, my heart started beating a little faster …" said astronomer David Kipping (left). He and Alex Teachey (right), both from Columbia University, could be co-discoverers of the 1st exomoon.

Instead, astronomers have discovered most of the known exoplanets – and this exomoon – as they pass by their stars. Such an event calls for a transitand causes a slight dip in the light of the star. The transit method was used to detect most of the known exoplanets cataloged to date.

The transit signals of distant exoplanets are extremely weak. This is why the search for exoplanets lasted decades before the first exoplanets were confirmed in the 90s. Exomoons are even more difficult to detect than exoplanets because they are smaller and their transit signal is weaker. . The Exomoons also change position at each passage because the Moon is orbiting the planet.

David Kipping has spent about a decade of his career researching exomoons. In 2017, with his team, he analyzed the data of 284 exoplanets discovered by the Kepler satellite, a planet hunter. They examined the exoplanets in relatively large orbits, more than 30 days, around their host stars. The researchers discovered a case, in Kepler-1625b, of a transit signature with intriguing anomalies, suggesting the presence of a moon. Kipping said:

We saw small deviations and oscillations in the light curve that caught our attention.

Kipping then asked about the time on the Hubble Space Telescope. Hubble's new findings – though inconclusive – seem to confirm the earlier finding of an exomoon for Kepler-1625b. The announcement of the discovery on HubbleSite explained:

Based on their findings, the team spent 40 hours observing with Hubble to study the planet intensively – also using the transit method – by obtaining more accurate data on the hollows of light. Scientists watched the planet before and during its 19-hour transit through the star's face. After the end of the transit, Hubble detected a second, much smaller, decrease in star brightness about 3.5 hours later. This small decrease is consistent with a gravitational moon chasing the planet, much like a dog following its owner.

Unfortunately, Hubble's scheduled observations ended before the complete transit of the candidate moon could be measured and its existence confirmed.

Kipping said:

A companion moon is the simplest and most natural explanation for the second trough of the light curve and the timing deviation on the orbit.

It was really a shocking moment to see this Hubble light curve; my heart started beating a little faster and I kept looking at this signature. But we knew that our job was to keep a cool head and assume it was wrong, by testing every conceivable means by which the data could deceive us.

Jonathan McDowell tweeted:

(ie the exomoon should be called "Kepler-1625b I" rather than "Kepler-1625b-i" … unless I miss something?)

– Jonathan McDowell (@ planet4589) October 3, 2018

The moon of the Earth is known to be a major factor in the evolution, even the presence, of life on our planet. This possible exomoon and its host planet are in the habitable zone of their star, the region around a star where liquid water could exist on planetary surfaces. Could the planet or its moon support life? The answer is probably no. The exoplanet Kepler 1625b – and its possible exomoon – are both gaseous, rendering them unfit for life as we know them.

These astronomers have stated that future research will exomoons:

… will target planets the size of Jupiter farther from their star than the Earth will be from the sun. Ideal candidate planets hosting moons are in large orbits, with long and infrequent transit times. In this research, a moon would have been among the easiest to detect because of its large size.

Currently, the Kepler database contains only a handful of similar planets.

As future observations confirm the existence of the Kepler-1625b moon, NASA's next James Webb space telescope will be used to find candidate moons around other planets, with much more detailed details than Kepler's.

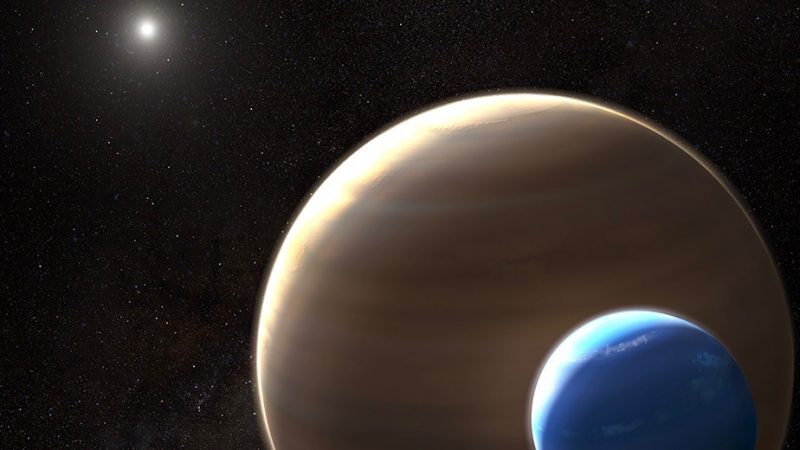

Artist's concept of a possible moon of Neptune's size, gravitating around a planet several times larger than Jupiter – the largest planet in our solar system – in a distant solar system, some 8,000 years distant light. Image via HubbleSite.

In summary: University of Columbia astronomers have discovered evidence in the Kepler probe data in 2017, suggesting an exomoon in orbit around Kepler-1625b. They then asked for time on the Hubble Space Telescope, and the new Hubble data reinforces the assertion – without conclusively proving – that this moon exists.

Source: evidence of a large exomoon orbiting Kepler-1625b

Via HubbleSite.

[ad_2]

Source link