[ad_1]

Getty

Climate change could lead to a global shortage of barley and, as a result, a rise in beer prices.

The price of beer could double under the effect of uncontrolled climate change, as droughts and extreme temperatures cause a drop in barley yields. This is one of the conclusions of the research we recently published in Nature Plants.

We began by focusing on barley and the beer it produces, which is a relatively minor crop that is clearly affected by climate extremes, yet it has never caught the attention of climatologists. And, unlike many other food crops, barley grown for beer is required to adhere to very specific quality parameters. Malted barley gives beer a great deal of flavor. However, if it is too hot or there is not enough water during the critical stages of growth, the malt can not be extracted.

That's why we have assembled a team of scientists based in China, the United Kingdom and the United States to assess the consequences of extreme drought and heat on beer supply and prices . We were particularly interested in what would happen to barley in case of extreme drought and heat during the growing season, which will become more common thanks to global warming. We then modeled what it would mean for barley yields in 34 regions of the world that produce or drink a lot of beer.

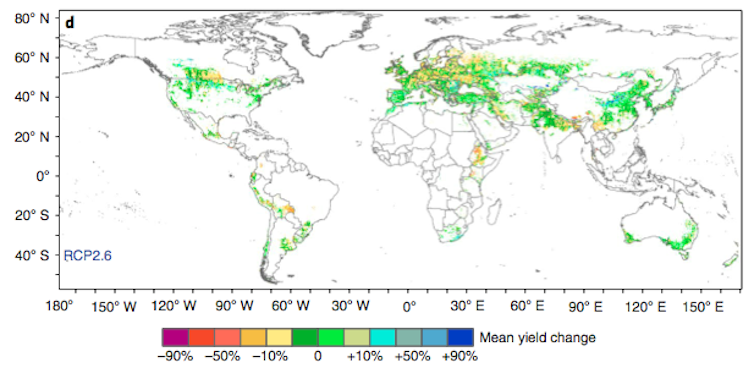

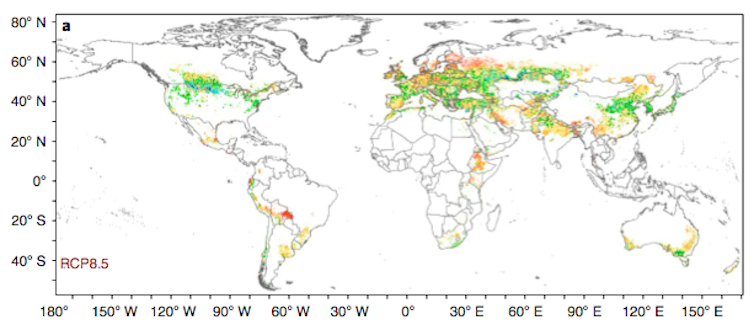

In more optimistic scenarios, where emissions are controlled and the warming is kept to a reasonable level (what climatologists call RCP2.6), droughts and heat waves can occur simultaneously in about 4% of the years. In the worst case scenario, where emissions and temperatures keep rising, such extremes could occur in 31% of the years.

However, these are overall average results that can mask significant regional variations. In the years affected, barley yields would fall most in the tropics of Central and South America, and Central Africa, for example. In the same years, yields in temperate Europe would decrease slightly or increase in parts of the United States or Russia.

Xie et al / Nature Plants

But the overall trend is clear: globally, barley yields will fall as much as possible – in the optimistic scenario – by 3%. And in the worst case, yields will fall by 17%.

Xie et al / Nature Plants

From barley to beer

We know that climate change will mean less barley – but what about beer? One factor to consider is that barley is mainly used to feed livestock and that beer is ultimately more essential than meat. This means that declining yields will weigh heavily on beer production.

In the end, our modeling suggests that during the worst weather events, the price of beer would double and that global consumption would decrease by 16%, or 29 billion liters. This is roughly equal to the total annual beer consumption of the United States. Even in the optimistic scenario of less extreme climate change, beer consumption would still decrease by 4%.

Again, changes in prices and consumption would vary considerably from one country to another, with the largest price increases being concentrated in relatively affluent and historically beer-loving countries. In Ireland, for example, the price of a bottle of beer would double under extreme climate change. In less wealthy countries, people simply drink less beer in these circumstances. We expect a decline of 32% in Argentina, for example.

PHTGRPHER_EVERYDAY / Shutterstock

It is possible that barley cultivars that are more resistant to drought or heat may be developed in the future, which would reduce the risk of climate change related to beer supply. But these and other technological developments, or the increase in stocks (or even the priority given to beer versus livestock), were outside the scope of our study.

While previous research had examined in detail what climate change meant for key commodities like wheat or rice, there was less interest in "luxury" products. In our study, we took beer as an example, to highlight the effects of climate change on our lives.

We hope our results will attract more attention from different beer lovers who have the power to do something to combat global warming. Seeing that climate change is affecting our lives more than we had imagined before, they could begin thinking about further strengthening global efforts to reduce emissions.![]()

By Tariq Ali, Postdoctoral Researcher, China Center for Agricultural Policy, Peking University; Dabo Guan, professor of climate change economics, University of East Angliaand Wei Xei, Assistant Professor at the China Center for Agricultural Policy, Peking University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source link