[ad_1]

The statistics of the First World War are horrible. Estimates vary, but in total there were about 40 million military and civilian casualties – 20 million dead and 21 million injured. Never before has a conflict engendered such devastation in terms of the dead and wounded. In response, during the four years of the war, military surgeons developed new techniques on the battlefield and in support of hospitals, which, during the last two years of the war, made more survivors injuries that would have been fatal in the first two.

On the Western Front, 1.6 million British soldiers were successfully treated and returned to the trenches. By the end of the war, 735,487 British soldiers had been released as a result of serious injuries. The majority of injuries were caused by explosions of shells and shrapnel.

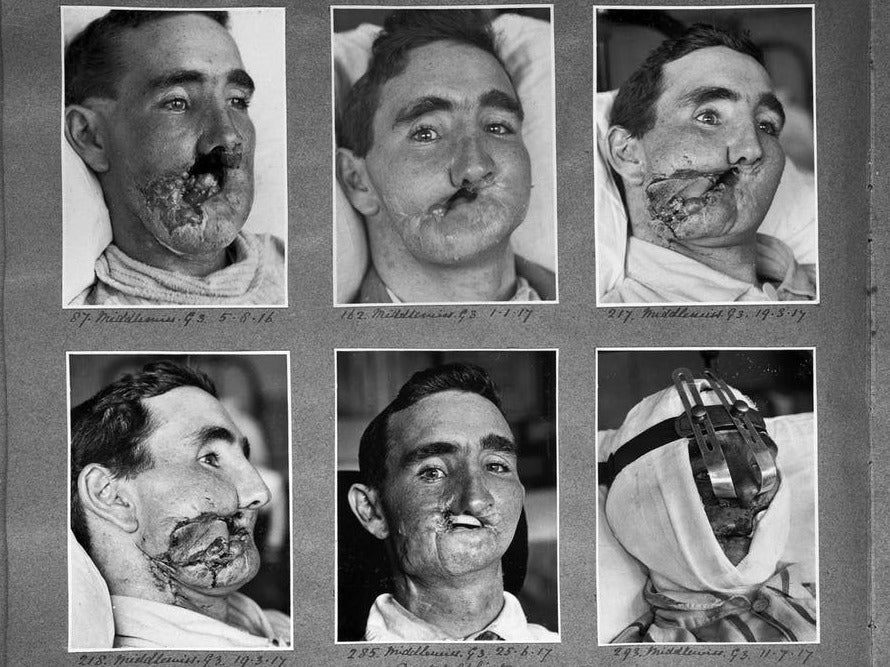

Many of the injured (16%) had facial injuries, more than a third of which were classified as "serious". Historically, this was an area where very few attempts were made and survivors with serious facial injuries were severely deformed, making vision, easy breathing, food and beverages difficult.

A young ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgeon from New Zealand, Harold Gillies, working on the Western Front, attempted to repair the damage caused by facial wounds and realized the need for 39, specialized work. The timing was opportune, as the military medical authorities recognized the benefits of establishing specialized centers for the treatment of specific injuries, such as neurosurgical and orthopedic injuries or gassing victims.

Gillies is authorized to do so, and in January 1916 he set up the first British plastic surgery unit at Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. Gillies visited basic hospitals in France to search for suitable patients to send to her unit. He returned in expectation of about 200 patients – but the opening of the unit coincided with the opening of the Somme offensive in 1916 and more than 2 000 patients with facial lesions were sent to Aldershot. Treatment was also necessary for sailors and airmen suffering from facial burns.

A new strange art

Gillies described the development of plastic surgery as a "new and strange art". Many techniques have been developed through trial and error, although some reflect work done centuries ago in India. One of the main techniques developed by Gillies was tube pedicle skin grafting.

1/10

Vanellope has been transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit where she will remain for several weeks, while she recovers

Pennsylvania

2/10

The doctors recommended that Vanellope's parents stop their treatment because their chances of survival were so low.

Leicester University Hospital NHS Trust / PA Wire

3/10

The baby was immediately wrapped in a sterile plastic bag after birth

Pennsylvania

4/10

The child is born with an extremely rare disease, Ectopia cordis, in which the heart grows outside the body.

Pennsylvania

5/10

Surgeons said the baby's hopes of survival were less than 10%.

Leicester University Hospital NHS Trust / PA Wire

6/10

The surgeons had to move Vanellope's heart as well as part of his stomach into his chest

Pennsylvania

7/10

The surgeons created a net that protected the heart because it had neither ribs nor sternum

Pennsylvania

8/10

While her organs compete for space in her chest, Vanellope is still attached to a ventilation device.

Pennsylvania

9/10

Naomi Findlay and Dean Wilkins with their daughter

Pennsylvania

10/10

Vanellope Hope Wilkins could now be the first case of ectopia cordis successfully treated in the UK

Pennsylvania

1/10

Vanellope has been transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit where she will remain for several weeks, while she recovers

Pennsylvania

2/10

The doctors recommended that Vanellope's parents stop their treatment because their chances of survival were so low.

Leicester University Hospital NHS Trust / PA Wire

3/10

The baby was immediately wrapped in a sterile plastic bag after birth

Pennsylvania

4/10

The child is born with an extremely rare disease, Ectopia cordis, in which the heart grows outside the body.

Pennsylvania

5/10

Surgeons said the baby's hopes of survival were less than 10%.

Leicester University Hospital NHS Trust / PA Wire

6/10

The surgeons had to move Vanellope's heart as well as part of his stomach into his chest

Pennsylvania

7/10

The surgeons created a net that protected the heart because it had neither ribs nor sternum

Pennsylvania

8/10

While her organs compete for space in her chest, Vanellope is still attached to a ventilation device.

Pennsylvania

9/10

Naomi Findlay and Dean Wilkins with their daughter

Pennsylvania

10/10

Vanellope Hope Wilkins could now be the first case of ectopia cordis successfully treated in the UK

Pennsylvania

A flap of skin was separated, but not detached from a healthy part of the soldier's body, sewn into a tube, and then sutured to the injured area. A period of time was required to allow a new blood supply to form at the site of implantation. It was then detached, the tube open and the flat skin sewn on the area to be covered.

One of the first patients to have been treated was Walter Yeo, artillery warrant officer on the HMS Warspite. Yeo was wounded in the face during the Battle of Jutland in 1916, including the loss of his upper and lower eyelids. The pedicle of the tube produced a "mask" of grafted skin on the face and eyes, producing new eyelids. The results, although far from perfect, gave him a face. Gillies then repeated the same type of procedure on thousands of others.

It was necessary to have larger facilities for surgical and postoperative treatment, as well as for the rehabilitation of patients, as well as the different specialties involved in their care. Gillies played a large role in designing a specialized unit at Queen Mary's Hospital in Sidcup, South East London. It opened with 320 beds – and by the end of the war there were over 600 beds and 11,752 operations had been carried out. But reconstructive surgery continued long after the end of hostilities: some 8,000 soldiers were treated between 1920 and 1925. The unit was finally closed in 1929.

The details of the wounds, the operations to correct them and the final results were all recorded in detail, both by old clinical photographs and by detailed drawings and paintings created by Henry Tonks who, although a doctor, had abandoned the drug for painting. Having become a war artist on the Western Front, Tonks then joined Gillies to help not only register the new plastic procedures, but also plan them.

The only real advances

The complex surgery of the face and the head required new methods of anesthesia. Anesthesia had generally evolved as a specialty during the war years – both by the way it was administered and by the training of doctors (previously, anesthetics were often administered by a lower limb of the doctor). surgical team).

Support freethinking journalism and subscribe to Independent Minds

The survival of operations requiring anesthesia improved, although the techniques still relied on chloroform and ether. The Queen Mary's anesthetic team has developed a method for passing a rubber tube from the nose to the trachea (trachea), as well as working on the endotracheal tube (from the mouth to the trachea), made from commercial rubber tubes. Many of their techniques remain in use today. In 1935, an Austrian doctor wrote:Nobody has won the last war but the medical services. Increasing knowledge was the only determinable benefit for humanity in a devastating catastrophe. "

Robert Kirby is Professor of Clinical Education and Surgery at Keele University. This article was first published on The Conversation (theconversation.com).

The author would like to thank Norman G Kirby, Major General (Retired), Director of the Army Surgery Service, 1978-1982.

Source link