[ad_1]

The analysis of elephant bones, once the largest bird in the world, revealed that humans had arrived on the tropical island of Madagascar more than 6,000 years earlier than expected. They have apparently lived alongside giant birds for thousands of years, hunting them and skinning them for food as needed. In addition to pushing back the date of human migration to Madagascar, the study also shed new light on the role of humans in the extinction of the megafauna of the island.

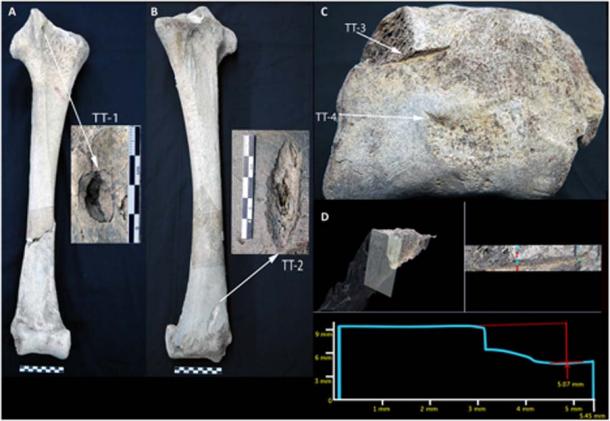

A team of scientists led by ZSL (Zoological Society of London), an international conservation charity, has discovered that ancient elephant bones of Malagasy origin (Aepyornis and Mullerornis) show signs of cut and depression compatible with the hunting and butchery. The elephant birds weighed at least half a ton, measured at least 3 meters (9.84 feet) high and laid huge eggs.

Using radiocarbon dating techniques, the team was able to determine when these giant birds were killed by reassessing them when humans reached Madagascar for the first time. They published their findings in the journal Scientists progress .

Previous research on lemur bones and archaeological artifacts suggested that humans arrived in Madagascar 2,400 to 4,000 years ago. However, the new study provides evidence of human presence in Madagascar 10,500 years ago – making these modified elephant bones the first known evidence of humans on the island.

Disarticulation marks on the basis of tarsometatarsus. These cut marks were made during the removal of the toes of the foot. ( ZSL)

Lead author, Dr. James Hansford of the Zoology Institute of ZSL, said, "We already know that the megafauna of Madagascar – elephant birds, hippos, giant tortoises and giant lemurs – s" extinct less than 1,000 years ago. This has happened, but the extent of human involvement has not been clear. He continued:

"Our research provides evidence of human activity in Madagascar more than 6,000 years earlier than previously thought – demonstrating that a radically different theory of extinction is needed to understand the immense loss of biodiversity. on the island, birds and other species that have been lost for more than 9,000 years, apparently with a limited negative impact on biodiversity for most of this period, offering new perspectives for conservation today. "

(A) Depression fracture on the anterior fascia of the proximal end of A. maximus tibiotarsus of the Christmas River. ( BDepression fracture on the lateral aspect of the posterior fascia. ( CDistal aspect of the tibiotarsus showing two cutting marks (TajT-3 and TT-4). ( re) Close-up and profile of the TT-3 cut mark on the medial condyle of the distal joint process (the thin digital section shows the wall and floor of the mark). ( V. R. Perez, University of Massachusetts Amherst )

The co-author, Professor Patricia Wright of Stony Brook University, said:

"This new discovery reverses our idea of the first human arrivals, and we know that at the end of the ice age when humans used only stone tools, there was a group of humans arriving in Madagascar. We do not know the origin of these people and we will not know until we find other archaeological evidence, but we know that there is no evidence of their genes in modern populations. The question remains: who were these people? And when and why did they disappear? "

The bones of the elephants studied by this project were discovered in 2009 in the Christmas River in south-central Madagascar – a fossil "bone bed" containing a rich concentration of remains of ancient animals. This marsh site could be a major destruction site, but additional research is needed to confirm.

Site of excavations of the Christmas river in Madagascar. ( ZSL)

Top Image: Giant elephant birds, once the largest birds in the world, may have coexisted with people for millennia. Source: Velizar Simeonvski

The article, originally titled Ancient bird bones reduce human activity in Madagascar by 6000 years " was originally published on Science Daily.

Zoological Society of London. "The ancient bones of birds reduce human activity in Madagascar by 6,000 years: 500 kg elephant skeletons disappeared revolutionize our understanding of this island." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, September 12, 2018.

The references

James Hansford, Patricia C. Wright, Armand Rasoamiaramanana, R. Pérez Ventura, Laurie R. Godfrey, David Errickson, Tim Thompson, Samuel T. Turvey. Human presence of the lower Holocene in Madagascar highlighted by the exploitation of the Avian megafauna . Scientists progress 2018; 4 (9): eaat6925 DOI: 10.1126 / sciadv.aat6925

[ad_2]

Source link