[ad_1]

Have you ever lived long in your health? Or perhaps, you have noticed that a friend has moved to the U.S.

Many immigrants arrive in the U.S. healthy. But after living in this country for a decade, they are at a very high risk of developing obesity. This is not just because these immigrants change their diets or increase caloric intake. Something else is going on. We believe that this part of the problem is a change in microscopic creatures that lives inside us – the human microbiome.

Pajau Vangay, CC BY-SA

In our lab at the University of Minnesota, we study the world of microbes that live in the digestive tract, called the gut microbiome, because these invisible creatures are very important for human health. They help us break down that we can not digest ourselves, help our immune systems and help us fight off infections. Changes in the gut microbiome are now associated with nearly every major chronic human disease. In fact the data suggests that the microbiome, and changes to it, can cause many of these diseases, including obesity.

Our recent research study, The Immigrant Microbiome Project, explores what happens to people's gut microbiomes and their health when they move to a developing country to the US We also want to know about these changes may cause obesity.

Gut microbiome diversity falls after move to US

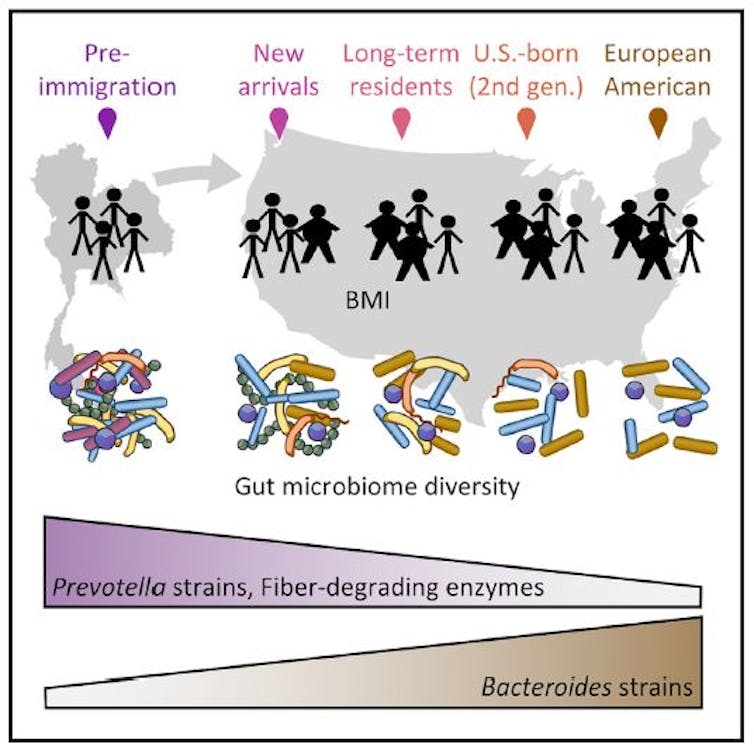

We studied two Asian ethnic groups. One was the Hmong, an ethnic group from the mountainous regions of China, Vietnam, Laos and Thailand. The second was the Karen, an ethnic group from Myanmar and Thailand. The participants from both groups were born in Asia, but then moved to the U.S., becoming first-generation immigrants. We also studied second-generation immigrants, who were born in the U.S. as children of first-generation immigrants.

Having many different species of microbes in the gut is associated with good health. A diverse range of species is more versatile and resilient, with various gut microbiomes and a range of tools – genes – to fight against, and recover from, various threats and disturbances. For example, when antibiotics deplete a microbiome, the gut may be colonized by the pathogenic microbe Clostridium difficile.

In our study, we found that the diversity of gut microbes in Hmong and Karen in the U.S. and those who were obese had an even greater decline in diversity.

We know from previous studies that in general, obese individuals have a lower microbe diversity in their guts than their lean counterparts. But asians were still more likely than Asians who had immigrated to and were living in the US We also found that the children of immigrants had fewer microorganisms than their parents. This suggests that the modern lifestyle in the United States may be causing an anemia.

Microbiome Gut Westernized immediately after relocation

In addition to just logging the number of different species, we were also interested in knowing the identity of the different types of bacteria living in the guts of our participants. Bacteroides, which are commonly found in Westernized countries, and Prevotella, which are common in non-Western countries.

These two bacteria are not necessarily good or bad; they are simply dominant members of the gut microbiomes in different populations around the world. When we examined the problem of microbiology in our study, we found that, as expected, all of the patients who were residing in Asia had very high proportions of non-Western Prevotella. But what we discovered was surprising.

We discovered that immediately after immigrants moved to the U.S., Bacteroides strains started to replace their native Prevotella strains. After a decade, first-generation immigrants are no longer dominated by Prevotella, but rather by the U.S.-associated Bacteroides.

Vangay et al. / Cell, CC BY-SA

Diet explains some changes to the gut microbiome

The obvious explanation for all of these changes is diet, since it is one of the strongest drivers of what species of microbes live in a person's gut. We found that immigrants who lost Prevotella strains also lost highly specialized enzymes. These included palm, coconut, konjac and tamarind, which are commonly eaten in Southeast Asia. It is likely that the immigrants we studied had stopped eating some of these traditional foods after immigration, and the microbes that relied on those plant nutrients failed to grow and multiply and died off.

Although some of the microbes that U.S. immigrants begin to lose significantly, they are more likely to be affected by their diet. We could not explain all of the changes in microbiology using dietary data alone, as they are also affected by the microbiome. These factors could include water sources, antiparasitics or antibiotics, other medications, physical activity, mental health and other environmental exposures.

Although we see that immigration-related microbiome changes are even stronger in obese individuals, we can not test whether the microbiome is actually causing obesity in our cohort. However, previous studies have shown that having the wrong microbes can cause obesity in mice. It is our hope that we can identify certain dietary interventions that will help immigrants stay metabolically healthy, or provide certain microbes that can be used as therapeutics to prevent or treat obesity.

Source link