[ad_1]

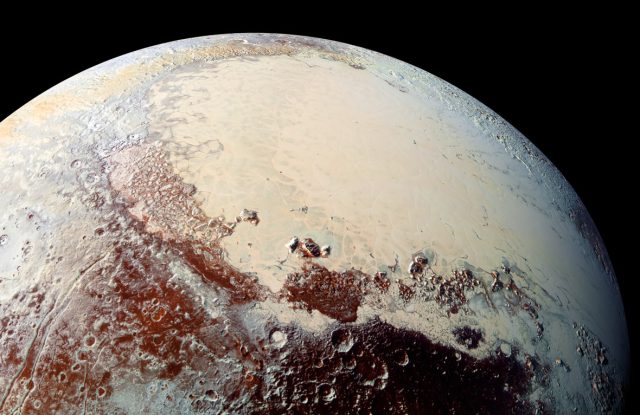

New Horizons revealed Pluto as a mysterious world, with icy mountains and very smooth plains.

NASA

Three years ago, when the New Horizons spacecraft sank to Pluto on July 4th. from the tiny world to the end of the solar system, everything seemed preordained.

Of course NASA would fund and build a spacecraft to complete its initial study of the solar system and visit the only "planet" found by an American. (For the purposes of this article, we will set aside the debate on Pluto's project.) But as always in spaceflights, the end result seems almost always easier and smoother to the casual observer than the reality messy of those who actually do it.

For example, anyone watching a spacewalk on NASA's television will see splendid views of the Earth in the background while two astronauts float holding amusing tools, unscrewing slowly or by installing this. Everything looks so easy. Yet these six or seven hours in space represent the culmination of years of training, and the EVA activity itself is also physically painful for astronauts in their combinations cumbersome space than running a marathon.

Today, we can hardly think of Pluto and its moons without evoking in our mind the iconic image of the reddish and brownish world that does not resemble anything other than one. heart. The reality, however, is that we almost did not have these images of Sputnik Planitia or the ghostly atmosphere of Pluto. Rather, it seems like a miracle we did.

-

Taken on July 13, 2015. This image is the last and most detailed sent to Earth before the closest approach to Pluto on July 14th. discoveries.

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute -

This is the farthest color departure plan from the receding Pluto crescent of NASA's New Horizons spacecraft, when the spacecraft was 200,000 km Pluto.

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Laboratory of Applied Physics / Southwest Research Institute -

One of the strangest reliefs discovered by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft when it flew over Pluto last July was the terrain " blade "to the east of Tombaugh Regio. name given to the large surface of Pluto.

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute -

Two different versions of an image of Pluto's misty layers, taken by NASA's New Horizons while he was looking at the dark side of Pluto near 16 hours after a distance of 480,000 miles (770,000 kilometers).

NASA / Johns Hopkins University Laboratory of Applied Physics / Southwest Research Institute -

A Closer View of Sputnik Planitia.

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI -

The moon of Pluto Charon (improved colors).

-

A newly discovered mountain range lies near the southwestern margin of Pluto's Tombaugh Regio (Tombaugh area), located between clear, icy plains and dark, heavily cratered terrain.

-

A close-up showing the jagged peaks of Norgay Montes de Pluto, some of which reach 3,500 m. The late evening sunlight captures how rugged this terrain is.

-

Pluto and its moon, Charon, are very different despite their formation at the same time and in the same place.

NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI -

A close-up zoom on the day / night border of the image reveals long hazy shadows projected by the hills. The atmosphere of Pluto has a complex structure, with several layers, some of which form dense clouds.

-

Best still picture of the small moons of Pluto, Nix and Hydra.

-

The icy mountains of Pluto and a surprising lack of nearby impact craters.

-

The ridges of Tartarus Dorsa.

-

The first official surface names of Pluto are marked on this map, compiled from images and data collected by NASA's New Horizons spacecraft during its flight through the Pluto system in 2015.

] Chasing New Horizons written by New Horizons lead researcher at Pluto, Alan Stern, and co-author David Grinspoon. The story of New Horizons is as fascinating as the breathtaking images and discoveries

Voyager and Pluto

NASA could spy on Pluto decades ago with the world's most iconic planetary science missions all the time. Travelers. Although the trajectory of Voyager 2 did not approach Pluto's orbit, the Voyager 1 spacecraft could have reached the tiny world five years after its Saturn flight in 1980.

Scientists of the mission faced a dilemma: visiting Titan or Pluto. They could either perform a maneuver immediately after passing Saturn that would bring the spacecraft near Titan; or they could pass a tight flyby of Titan, maneuver towards Pluto, and roll their dice on Surviving Voyager for another five years. In the end, Titan, with its thick and tempting atmosphere, prevailed. Little regret for this decision today.

After the Voyagers, NASA was eager to send probes dedicated to Jupiter and Saturn to better explore these complex worlds and their dozens of intriguing moons that the Voyagers had observed. These became the Galileo and Cassini probes. But Stern, a graduate student in the late 1980s, began to wonder why NASA was not going to finish its exploration of the solar system by sending a probe to Pluto.

He soon found (or crooked arm) some scientific allies to join him in these emerging planetary scientists, such as Fran Bagenal. At first, they decided to convene a session at the meeting of the American Geophysical Union in 1989. This would begin the process of building consensus in the scientific community for such a mission.

Just before the meeting, Stern went to visit with Geoff Briggs, who then directed the solar system's exploration for the space agency, at NASA's headquarters. In the book, Stern remembers telling Briggs: "With Voyager coming to an end, why not finish the solar system's exploration work? Would you like to fund a study on how to to make a mission to Pluto? "

Briggs was immediately enthusiastic. "You know, no one has ever asked me about it before – it's a wonderful idea, we should do it." That would be Stern's last true enthusiasm for a long time.

Source link