[ad_1]

Multimedia playback is not supported on your device

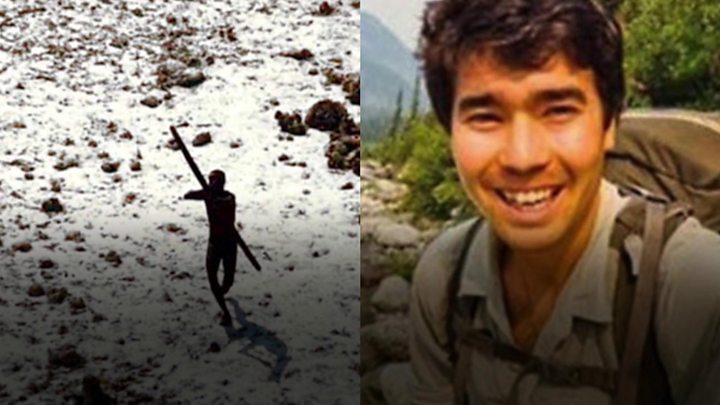

When the American John Allen Chau was killed by a threatened tribe in India last week, this brought renewed interest to some of the world's most isolated people.

Indian officials said Chau was a missionary anxious to convert the Sentinel Protected People on the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

But the Sentinels, who are afraid of strangers, attacked Chau with bows and arrows.

Supporters of isolated communities, such as Survival International, based in London, believe that Chau's assassination should remind that isolated tribes must be protected from the outside world.

And an anthropologist interviewed by the BBC said there was a risk that such incidents could lead people to falsely assume that all tribes are leading "nasty, brutal and short lives".

In fact, the experts have highlighted many lessons that developed countries could draw from distant tribes. Here are some examples.

You can not have peace without equality

Copyright of the image

AFP

The Piaroa people, which has about 14,000 people, live near the Orinoco in the state of Amazonas, Venezuela.

What could we learn from them?

It is possible to live in total equality – and this can create a peaceful community.

There is a problem: it is to become anarchist. No government, no state, only the individual and his willingness to do what he likes.

Piaroa renounces violence and does not punish children physically. They believe that peace is achieved by removing the concepts of property, competition, vanity and greed.

No sport is practiced, the land is not owned, no one can order someone to work and the focus is on learning from others. It is not that there is deference to the elders – it would make society hierarchical and mean that everyone is not equal.

The idea of the individual is the most important thing, although it does not promote egoism. It is up to each person to choose what she does, how and when, and she does not judge the decisions of others.

In a 1989 essay, American-born professor Joanna Overing writes: "The Piaroa daily expresses its right to choose in private and its right not to be subject to domination over a wide range of subjects , such as residency, work, personal development, and even marriage. "

Copyright of the image

AFP

And since it is a society of absolute equals, men and women share the same status (this status is not a thing).

Anyone who tries to conform to traditional images of manhood, such as the hunter, is subject to pity and lack of self-control.

- Who was the American man killed in the remote islands?

- The sad truth about isolated tribes

The idea of becoming a man does not exist, writes Professor Overing. "The young men of Piaroa also do not learn the virtues of virility that would place them as men against women and, as such, superior to them.

"Every woman is the mistress of her own fertility for which she alone is responsible: the community has no legal rights over her offspring, nor does her husband in the event of divorce."

You have to find your own melody

Copyright of the image

Gill Conquest / Jerome Lewis

The Bayaka are a group of hunter-gatherers who live in the humid tropical forests of Central Africa.

What could we learn from them?

That you must find your own place in society.

For the Bayaka, music is a central element of their identity and experts say that the style they like has even conditioned their behavior.

"The music that the Bayaka sing is these dense polyphonies, which means that each member … will sing a different melody and by combining them, you will create a song," says Jerome Lewis, an anthropologist who has been studying the band for over two decades. .

Multimedia playback is not supported on your device

He says that the way each person sings his own melody reflects the great importance Bayaka places on the individual.

"It takes you to be different and these companies attach great importance to autonomy," he says. "Once children can walk, they are free to decide where they sleep and who they associate with.

"You do not have the right to ask someone to do anything for you."

But when there are no leaders and when everyone is free to be an individual, how do the Bayaka learn to work together? Once again, the answer lies in the music.

- Spotlight on "Tribal Tourism"

"Regular participation in this style of singing is what taught people how they would coordinate their daily lives," says Lewis.

"You have to keep your own melody while others are singing different melodies," he says. "To cooperate and be effective together, you have to do something different.

"It's about an autonomy in which people are very sensitive to the needs of others and to their right to be different."

Modern life, modern bodies

Copyright of the image

Getty Images

A Yanomami girl in the Amazon rainforest in Venezuela

The Yanomami, an indigenous tribe living in the rainforests of northern Brazil and southern Venezuela, could help us better understand our own body.

What could we learn from them?

Research on the tribe, isolated from the outside world until at least the 1950s, shed light on how modern life could alter the composition of the human body.

A study conducted in 2015 examined a number of Yanomami villagers and revealed the most diverse collection of bacteria ever found in humans, including some that had never been detected in humans previously, said scientists.

They said it showed how modern diets, antibiotics and hygiene can reduce the range of bacteria in our body.

"Perhaps even minimal exposure to modern practices … can result in a drastic loss of bacterial diversity," said one of the study's authors, Jose Clemente, to the Toronto Star newspaper.

He added: "At every stage of Westernization, we seem to lose a lot of diversity."

- How can we stop antibiotic resistance

- Experts warn about "the post-antibiotic era"

The study also added to our understanding of antibiotic resistance.

For years, health professionals have warned that over-consumption of antibiotics complicates the treatment of infections by creating drug-resistant superbugs.

This study revealed that Yanomami villagers had unique genes resistant to antibiotics, whereas they had never taken any medication before.

This has provided further evidence that bacteria in our body can already resist antibiotics even before they have been attacked.

Slow down, calm down

Copyright of the image

Mark Plotkin

Dr. Mark Plotkin with a leader of the Sikiyana tribe on the Brazil-Suriname border in October

Dr. Mark Plotkin spent 35 years studying how isolated tribes of the Amazon used plants for medicinal purposes.

What could we learn from them?

A slower life is a happier life.

Regardless of the medical discoveries (Dr. Plotkin's lameness, which US doctors could not help, was cured by an Amazonian shaman, he says), Dr. Plotkin says there is much to learn from the way of life isolated communities.

"What we are seeing is that people do not suffer from stress, heart disease, insomnia and that they spend time with their families.

"We may not be ready to give up our iPhone and iPad and never eat Thai food, but the lessons of life are clear: slow down, do not waste time worrying about it. things you can not do anything about, I try to live my life along these prescriptions. "

- The story of "the most lonely man"

Dr. Plotkin, who heads the Amazon conservation rights group, said that while developed countries have much to learn from simpler lifestyles, he recommended caution.

"We risk romanticizing them too much, just like the acceptance of Jesus and the fact that you will live forever, or that you settle in a city and that you think you have two cars and a computer.

"Do not break their lifestyle too much, but learn about it, just as there are good things you can learn from Western religion.

"But just as we should not overly romanticize aboriginal peoples, we should not demonize missionaries as [John Allen Chau]. "