[ad_1]

<! –

->

The video above simulates an interaction between the small magellanic cloud and the great magellanic cloud, 1 billion years ago. This shows a collision about 100 million years ago. And indeed, astronomers now think that this has happened.

Just a few years ago, astronomer Gurtina Besla of the University of Arizona used a computer to model what would have happened if, in the past, large and small clouds From Magellan collided. The simulation above comes from his work. She and her team predicted at that time that a direct collision would cause the southeast region of the little magellanic cloud – which astronomers call l & # 39; wing – move to the Great Magellan Cloud. On the other hand, if the two galaxies are simply passed one next to the other, the Wing stars should move in a perpendicular direction. Last week (October 25, 2018) – thanks to ESA's Gaia Space Observatory – Michigan astronomers were able to confirm that what Besla and her team had predicted is in the process of happen. L & # 39; wing is away from the main body of the Little Magellanic. They said that this observation provides:

… The first unequivocal proof that the small and large magellanic clouds have recently collided.

Magellanic clouds, visible from the southern hemisphere of the Earth, are known to be small satellite galaxies of our Milky Way. They are located not far from each other on the dome of the sky. Star motions in the smallest cloud prove the collision, but we had no data on these motions before Gaia, whose second data release dates back to April. Astronomers have exploited Gaia's data to learn more about our galaxy and its neighborhood in space. Here is another example. Astronomer Sally Oey of the University of Michigan, lead author of the study, said:

It's really one of our exciting results. You can actually see that the wing is its own distinct region that is moving away from the rest of the Little Magellanic Cloud.

Oey and his colleagues published their findings in The letters of the astrophysical journal.

The astrophotographer Justin Ng captured the panoramic view of our galaxy of the Milky Way, the shining star Canopus and the big and small magellanic clouds at sunrise, in September 2013, on Mount Bromo, in the is from Java. Learn more about this image.

A statement from the University of Michigan describes part of the process used by these astronomers to make their discovery:

In collaboration with an international team, Oey and undergraduate researcher Johnny Dorigo Jones examined the MSC for "fleeing" stars, or stars thrown from clusters within the MSC. To observe this galaxy, they used a recent publication of Gaia …

Gaia is designed to reproduce the image of the stars again and again for several years in order to trace their motion in real time. In this way, scientists can measure the movement of stars in the sky.

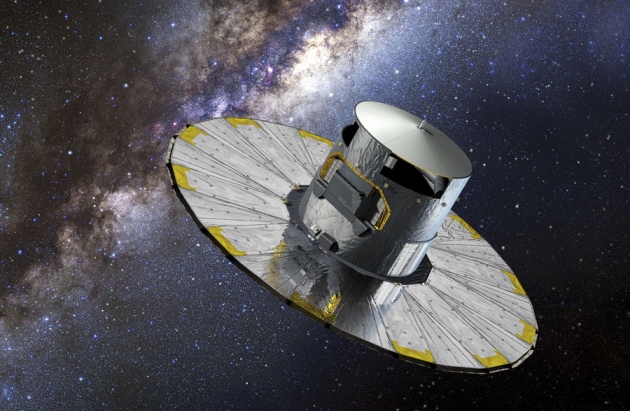

Gaia artist concept in space. Image via D. DUCROS / ESA.

Oey said:

We looked at very young very massive stars – the hottest and brightest stars, which are rather rare. The beauty of small magellanic clouds and great magellanic clouds lies in the fact that they are their own galaxies; we therefore examine all the massive stars of a single galaxy.

Examining the stars in a single galaxy helps astronomers in two ways, said the researchers. First, it provides a statistically complete sample of stars in a parent galaxy. Second, it gives astronomers a uniform distance from all stars, which helps them to measure their individual speeds. Dorigo Jones said:

It's really interesting that Gaia got the proper movements of these stars. These motions contain everything we examine. For example, if we observe someone walking in the cabin of a plane in flight, the movement we see contains that of the plane, as well as the much slower movement of the no one walking.

So we removed the overall motion of the entire small magellanic cloud in order to learn about individual star speeds. We are interested in the speed of individual stars because we try to understand the physical processes taking place in the cloud.

Oey and Dorigo Jones study the fleeing stars to determine how they were ejected from these clusters. In a mechanism, called a binary supernova scenario, a star in a gravitational link, the binary pair explodes like a supernova, ejecting the other star like a slingshot. This mechanism produces binary stars emitting X-rays.

Another mechanism is that a group of gravitationally unstable stars eventually ejects one or two stars from the group. This is called the dynamic ejection scenario, which produces normal binary stars. The researchers found a significant number of fugitive stars among X-ray binaries and normal binaries, indicating that both mechanisms are important for ejecting stars from clusters.

In reviewing these data, the team also observed that all of the squadrons – this southeastern part of the MSC – were moving in the same direction and at the same speed. This shows that the SMC and the LMC probably had a collision a few hundred million years ago.

Magellanic clouds – satellite galaxies of the Milky Way – via ESO / Wikipedia.

Dorigo Jones commented:

We want as much information as possible about these stars in order to better constrain these ejection mechanisms.

Everyone loves to marvel at images of galaxies and nebulae that are incredibly distant. The little magellanic cloud is so close to us, however, that we can see its beauty in the night sky with our unaided eye. This fact, together with Gaia's data, allows us to analyze the complex movements of stars in the small magellanic cloud and even to determine the factors of its evolution.

Conclusion: the motions of the stars in the small cloud of Magellan – as revealed by the Gaia space observatory – show that this small satellite galaxy of our Milky Way has collided with its larger neighbor in the past, the Great Magellanic Cloud.

Read more … Gaia's second publication: 1.7 billion stars!

Source link