[ad_1]

The NASA has published a report summarizing its official plans for the exploration of our solar system, making it an exciting read – if you do not mind it brings a dose of realism. Crewed missions on the surface of the moon; a semi-permanent base in orbit; a mission to return samples to Mars; All of these and many more are there, if not necessarily in the next decade.

The national space exploration campaign is the name of NASA's global plan to stop worrying about the LEO, abandon the ISS, win the next moon race and then return to Mars. It was, in a sense, the mandate of the Space Policy Chairman's Directive 1, which asked NASA to focus on the expansion and exploration of the solar system. A good goal, fortunately that the administration is already pursuing for a long time.

So the plan for the next decade or two years is very similar to what it was a few years ago, because, by necessity, these measures have to be applied over extremely long periods of time.

The simple truth is that even if we were going to do everything right now, it would be extremely difficult, not to say risky, to put boots on the regolith in 10 years. This is not because we can not do it, but that any future lunar mission should be part of a long-term strategy to take advantage of lunar orbits and landing gear in the pursuit of interplanetary travel. In other words, we could spend billions for a spectacular short-term Apollo hit, or we could invest billions of long-term infrastructure that could lead to significant dominance in a number of areas.

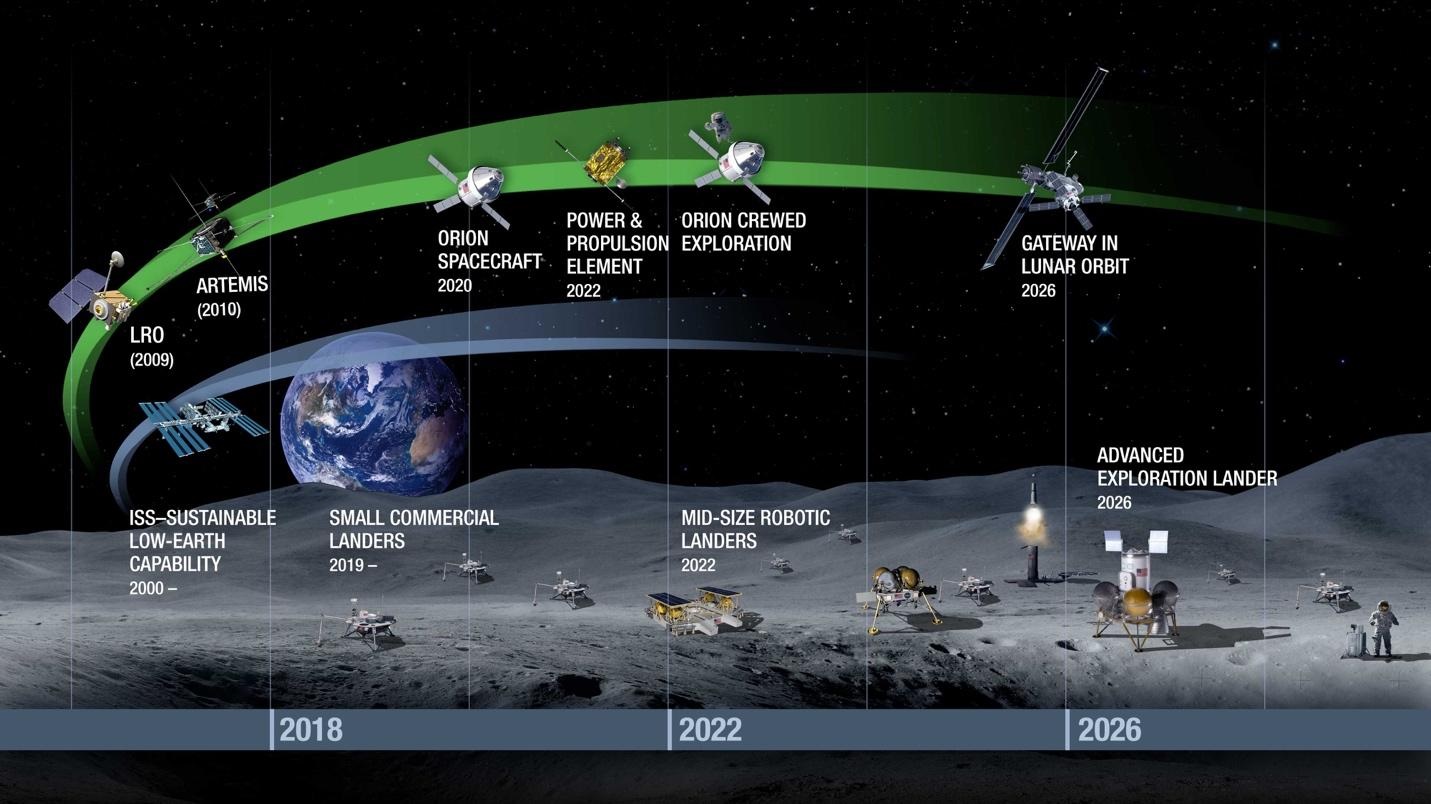

To this end, NASA has short-term, ambitious but achievable goals, and has blocked future projects, such as Lunar Gateway and Landers, behind the expected results of these efforts. After all, if the Orion spacecraft and the space launch system are delayed, or perhaps exceed expectations, this will impact the use of these systems to build and equip a permanent installation in lunar orbit.

His priorities are essentially the following three:

1. Strengthen the commercial space

NASA has launched launches at LEO, such as replenishment missions for the International Space Station, for decades. It's done and commercial projects are ready to take over.

"It is vitally important that a broad customer base emerge over the next few years to replace NASA's historic role in the LEO economy," the report says. Its objectives for the coming years are essentially to guide funding and contracts while conducting studies of efficiency, competition, etc.

Depending on the situation, the United States could eliminate direct federal funding for the ISS by 2025, relying instead on commercial suppliers. This does not mean that we are leaving the ISS – NASA would cease to be the one supplying supplies and astronauts.

Indeed, $ 150 million is planned to fund a new LEO business development program to potentially replace the ISS – or at least to put in place the necessary elements to do so. It would not have to be on the same scale, but an orbital platform or two to call our own would have be nice.

More generally, the release of the LEO company releases a ton of money and resources to NASA, which it can devote to more ambitious projects.

2. Trouble of the moon

The moon is a fabulous resting place for our planned exploration of the solar system. It is inhospitable like all hell, which means we can test things like Mars' habitats and radiation exposure in the space. There could be a ton of useful minerals under its moon dust coating, and possibly even usable water, which would greatly simplify the set up of a base.

Unfortunately, the last time anyone else set foot on the moon, several decades ago, there were very few returns, even with robotic undercarriages. So we will solve this problem.

We have plans for commercial lunar landing gear and rovers starting in 2019, that is, they will be in development and they will not land. Given their cost and success, other missions will be commissioned or undertaken to improve our basic understanding of the lunar surface, yet unknown in practical applications such as drilling, mining, etc.

Meanwhile, the Orion and SLS spacecraft will make their first orbital tests in 2020, and if all goes well, it could potentially deliver astronauts (and potentially small payloads) into lunar orbit a few years from now. Once proven, the Orion variant carrying cargo could orbit 10 tonnes of payload.

All this is preparatory to the establishment of the Moon Bridge, a space station orbiting the moon, which would be occupied by NASA astronauts and used as a test bench and laboratory. They will try to understand the basics – volume, mass, materials, technologies – by next year and want to have the first component in lunar orbit by 2022.

All this is preparatory to the establishment of the Moon Bridge, a space station orbiting the moon, which would be occupied by NASA astronauts and used as a test bench and laboratory. They will try to understand the basics – volume, mass, materials, technologies – by next year and want to have the first component in lunar orbit by 2022.

3. Remind everyone that we are already on Mars

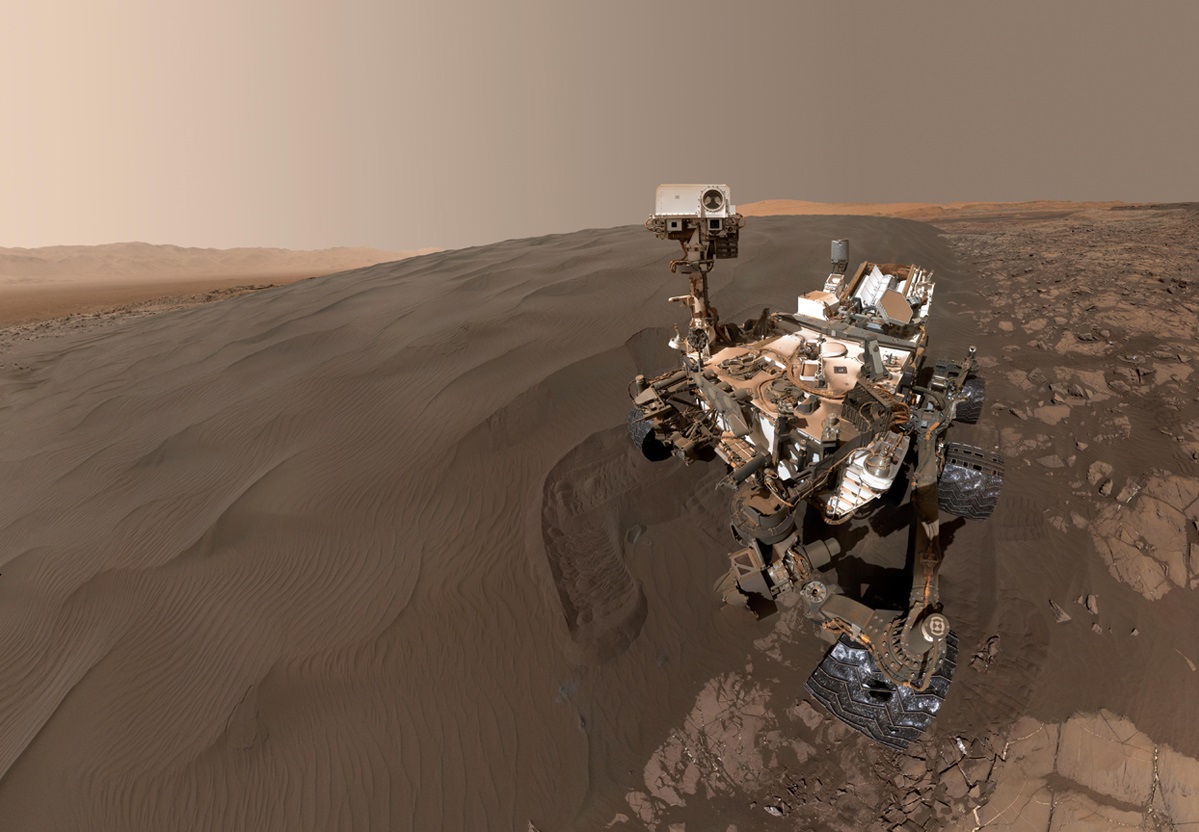

NASA is full of scientists, and asking them questions about a mission in the future will probably attract furious glances at the many Mars missions they are already juggling. Not surprisingly, the administration's roadmap focuses more on the near future than on the distant future. The fact is that Mars is already a priority and they already have large planned missions, but saying something about a mission or crewed base would be irresponsible and premature.

Insight is already on the way and will land in November; the March 2020 Rover is ready to take off next summer; both will produce all kinds of interesting results for planning future missions. March 2020 will take samples for a possible return via another mission in several years. Can you imagine what we can do with a hold full of Martian rocks? You better believe that we want to bring these things into the lab before sending a team to the outside.

2024 is the first time that NASA is committed to making a decision on a crewed Mars mission, perhaps in the 2030s – and even then it would be a matter of course. orbital mission. Of course, other missions will depend on incredibly valuable observations and lessons learned from this mission. We may be looking at the end of the 2030s to find boots on Mars.

Is it a little disappointing? Well, with the speed at which things are progressing in the commercial space, we could very well see a private Mars mission well before that. But NASA is subject to certain obligations, both as a scientific organization and as a taxpayer-funded organization, to justify its work and test it to a degree that private companies can choose not to use.

The report is heavy in terms of promises, but it is clear that policies and difficult dates must be respected, while many objectives are distant enough that they can not be effectively defined beyond "we the will know in 2024 ". a little frustrating in this period of rapid progress in space to have such distant and vague goals, but that's kind of the nature of the business.

In the meantime, there is no shortage of exciting developments from NASA or the many commercial space companies that are reinventing the entire industry. If you do not like the patient approach of NASA, we invite you to mount your own mission in space – no, really. You would not be the only one.

Source link