[ad_1]

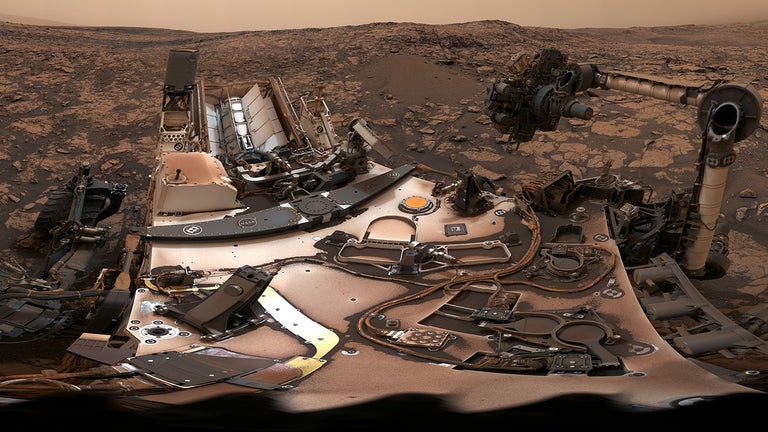

A new 360 degree panorama captured by the Curiosity Rover is one of its best.

The photos used to create this mosaic were taken by Curiosity on August 9, 2018, at Vera Rubin Ridge, where the intrepid rover has been working for several months. The image shows the iconic red planet, caramel color, although it is a little darker than usual due to a global dust storm that is dissipating.

Curiosity's counterpart, Rover Opportunity, is currently on the other side of the world where the storm was much worse. NASA had to put Opportunity into hibernation mode because the dust storm made it too dark for the solar panels of the rover to collect energy.

It's unclear when, or even if – Opportunity will return to active duty.

Anyhoo, Curiosity does not seem to have been affected by the storm, but as the new panorama shows, a good amount of dust has accumulated on its surface. The vehicle landed on Mars on August 6, 2012, and since then, it has been collecting dust, without anyone taking it away.

NASA claims that Curiosity has never studied an area where colors and textures vary enormously.

"The ridge is not that monolithic thing – it has two distinct sections, each with a variety of colors," said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity Project Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. "Some are visible to the naked eye and even more so when we look in the near infrared, just beyond what our eyes can see. Some seem to be related to the hardness of the rocks.

Indeed, hard rocks are a concern for the moment. Curiosity's most recent drilling attempt went well, but the two previous attempts to extract rock samples were not as successful as the rover drill could not penetrate through exceptionally hard rocks. The six-wheeled rover has used a new drilling method in recent months to solve a mechanical problem. To date, the new technique has worked well, corresponding to the effectiveness of the previous method. NASA says that the old technique would not have worked on hard rocks either, and that it was not a limitation of the new method.

NASA has no way of knowing how hard a rock will be before drilling, mission controllers having to make informed assumptions. As NASA writes:

The best way to find out why these rocks are so difficult is to drill them into a powder for the two internal mobile labs. Their analysis could reveal what is "cement" in the ridge, which allows it to resist despite wind erosion. According to Mr. Vasavada, the groundwater crossing the ridge in the past probably played a role in its strengthening, perhaps acting as a plumbing to distribute this "cement" anti-wind.

Much of the ridge contains hematite, a mineral that forms in the water. There is a hematite signal so strong that it draws the attention of NASA's orbiters as a beacon. Could some variation in hematite result in harder rocks? Is there anything special about the red rocks of the ridge that makes them so inflexible?

Looking at Curiosity's upcoming calendar, the rover will be extracting some rock samples later this month. In early October, the rover will climb higher on Mount Sharp as it heads to areas rich in clay and sulphites. There is no doubt that we will gather important scientific data, but we are also looking forward to the mobile view from this higher altitude.

For those of you who are looking to make this picture your wallpaper, go here.

[NASA]Source link