[ad_1]

Thirteen years outbound Earth and a trillion miles past Pluto, NASA's New Horizons Probe is healthy and on the road to a new year. project scientists say.

Unofficially dubbed Ultima Thule (pronounced TOO-lee) in a NASA naming contest, the small 20-mile-wide body is one of countless denizens of the vast Kuiper Belt extending beyond the orbit of Pluto, taking 296 years to complete the trip. sun. New Horizons is the first spacecraft to target a Kuiper Belt object, passing within 2,170 miles of Ultima Thule on Jan. 1.

"Ultima Thule comes from Latin and it means 'beyond the farthest frontiers,' which is exactly what we're doing," said Alan Stern, the New Horizon's principal investigator. "We're making the farthest exploration of worlds in the history of space exploration." The spacecraft is now about a billion miles farther out than Pluto, which itself has been farthest world ever explored. "

At Ultima Thule's distance of 4 billion miles from the sun – 43 times farther than Earth – it will take radio signals carrying high-resolution pictures, spectroscopic data and other priceless information, traveling at 186,000 miles every second, six hours seven minutes and 58 seconds to cross the gulf to Earth.

Given the enormous distance and the spacecraft's 30-watt radio transmitter, it will take 20 months to beam the treasure of data collected before, during and after the flyby. But a sampling of high-resolution images is expected to be collected at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory at the Evening of Jan. 1 and the morning of Jan. 2.

"Stern told reporters Wednesday at the American Astronomical Society's Planetary Sciences Division meeting in Knoxville, Tenn.

"We are going to an entirely new type of world, something that is much more important than anything else we have ever had in this world of deep solar system formation," he said.

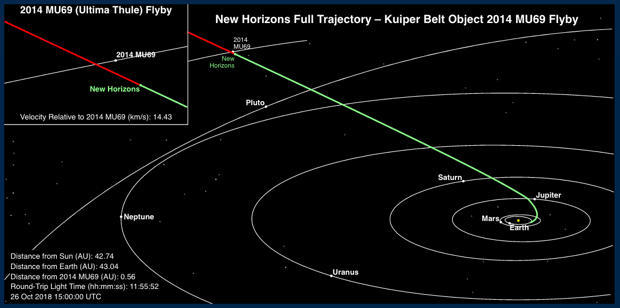

This plot shows the trajectory of the New Horizons spacecraft, from a launch in January 2006 through an encounter with Pluto in July 2015 and its upcoming New Year's Day flyby of a Ultimate Thule (formal name: 2014 MU69).

JHU Applied Physics Laboratory

Said Carey Smooth, a New Horizons Science Team Collaborator at the Applied Physics Laboratory: "If New Horizons" (Pluto) flyby, we're going to get surprised again. "

"Ultima Thule could be heavily cratered, highly pitted or it could even be smooth from ancient flows and ancient activity," he said. "We do not know, we're not going to be surprised."

Launched in January 2006, New Horizons flew past Jupiter in February 2007, using the giant planet's gravity to fling it onto a fast-track trajectory to Pluto. Even so, it took another eight years to reach its target in July 2015, flying past at a distance of 7,800 miles to collect the first close-up pictures of the famously demoted dwarf planet.

Hubble Space Hubble Space Telescope to the future of the future.

Ultima Thule was discovered by Hubble in 2014 and after the Pluto encounter, NASA managers approved a mission extension and New Horizons' course was adjusted to set up the Jan. 1 flyby.

Based on occultation observations in which Ultima Thule passed in front of a star background, scientists believe the target is either bi-lobed or elongated. New Horizons first "saw" its quarry on Aug. 16, at a distance of more than 100 million miles, but it is so much smaller than Pluto it appeared as a barely distinguishable pinpoint of light.

It will not be much more than until New Year's Eve.

"When we were 10 weeks out of Pluto, we could not find more space," Stern said. "Ultima Goal 10 weeks out is just a dot in the distance." And it will remain a dot in the distance until the day before the start.

"By the day after the flyby, we will have high resolution images, we hope for a better resolution than the best images of Pluto.

During the spacecraft's approach, scientists will use their cameras to scan the area Ultima Thule – the official name is 2014 MU69 – to look for any signs of dust, moonlets, rings or other possible dangers that might pose a danger to New Horizons . Flight planners can travel the spacecraft with an engine firing as late as mid December, moving the aim point farther away if required.

"There's some danger and some suspense because we do not know in detail what the hazard environment might be," Stern said. "Our spacecraft is traveling at 32,000 miles an hour, that's about 10 miles per second almost, and a collision with the smallest shard would probably be fatal to the spacecraft. and we're prepared to come to a place where we can be safer. "

Scientists do not know what to expect when New Horizons reaches Ultima Thule, but ground-based observations indicate it is an elongated body or a "bi-lobed" object like the artist's impression seen here.